It might have been the most difficult Secondary Road of all: a town centre in desperate need of relief, but with nowhere to squeeze in a bypass.

Greenwich town centre isn’t very big, but it is beautiful and full of historic buildings and tourist attractions. It’s rightly revered as one of London’s most special and valuable suburban centres. It is also plagued with traffic problems.

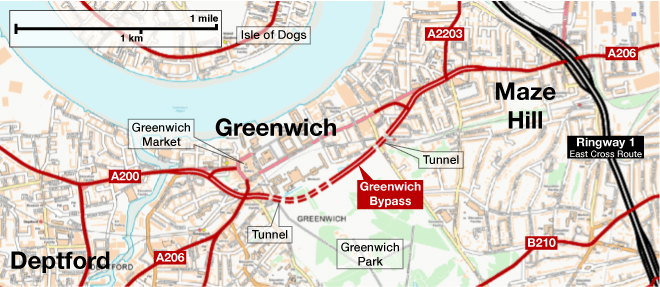

Surrounding the historic market are streets that function as an unsatisfactory roundabout, and converging on that are roads from all directions. But if you wanted to bypass it - and London’s planners did, in the hope of saving historic Greenwich from the effects of modern traffic - you quickly run into problems.

Greenwich is on the river, so you can't easily put a bypass to the north without getting wet. To the south is Greenwich Park, a handsome and peaceful space; further south, the land rises steeply and you reach the observatory and other things that cannot be disturbed. To the east, a large complex of naval buildings and Royal Palaces - mostly now university buildings and museums - form a precinct of architectural treasures that must be avoided at all costs.

There is no good way to send traffic through Greenwich and no good way around. The Greenwich Bypass is a story of attempts to find the least worst way to solve an intractable problem, and the sorry discovery that learning to live with the unhappy status quo might be the best we’ll ever do.

Outline itinerary

Continues from A200 Creek Road

A206 Greenwich High Road

Tunnel under Greenwich Park

A206 Trafalgar Road and A2203 Blackwall Lane

Continues as A206 Woolwich Road

Route description

This description begins at the western end of the route and travels east.

Deptford - East Greenwich

Between Deptford and Greenwich, the A200 Creek Road would widen to a dual carriageway just east of the Deptford Creek Bridge, and the long terrace of houses on the south side of the road would all be cleared to make way for a gentle curve on to a new road heading south east. A signalised T-junction would provide a connection to the remainder of Creek Road towards the town centre.

Heading south east across St Alfege Park, which would be effectively destroyed by the scheme, another signalised junction at the railway bridge near St Alfege’s Church would link to the A206 Greenwich High Road. The street past the front of the church, leading in to the town centre, would be pedestrianised.

Continuing south east through what are now the university buildings, the Greenwich Bypass would enter a cut-and-cover tunnel just before King William Walk. It would then curve gently east as it passed under the park, emerging into the open again after passing the Queen’s House. On the site of the boating pond, footpaths would descend into the cutting to reach bus stops.

The road would pass through the playground in a cutting with sloped grassy sides before entering a second tunnel under Maze Hill, which would also then carry it beneath the railway. Emerging again at surface level, a new line would be cut through Woodlands Park Road and Tuskar Street to reach another signalised T-junction with the A206 Trafalgar Road. The bypass would then narrow down to flow into the next part of the A206.

Beyond this point, further improvements were planned, widening the A206 to dual carriageway through to the Ringway 1 East Cross Route.

In the meantime

Today, the traffic in Greenwich is the stuff of legend: in a city where the traffic is notoriously bad for so much of the time, it’s one of the small number of places that even Londoners will warn you against tackling. For most of the twentieth century, though, planners didn’t consider it a priority: masterplans of the 1930s and 40s ignore it, or at most sketch a second-tier road somewhere nearby.

By the 1960s, though, the London County Council was coming to view Greenwich as a problem that needed solving, first because traffic was forecast to rise steeply across the city, and second because it was increasingly viewed as a place with special value that required protection. Some preservationists, including the Royal Fine Art Commission, were pushing them to act.

Unfortunately it was also a place with special problems.

Its history means that Greenwich is inextricably linked to royalty, the Royal Navy and the early development of astronomy and physics. It bristles with listed buildings, protected military sites, Royal parkland and protected sightlines. Greenwich is a highway planner’s nightmare.

More than a century earlier, Greenwich was one of the first places to get a railway line to London: but even in the cavalier days of railway mania, when private companies were given the freedom to build towering viaducts through communities across London and punch new holes in the Roman city walls at Chester, the railway tracks at Greenwich were deeply reverent to their surroundings.

Kept out of the park altogether, the railway runs underneath the lawns next to Trafalgar Road, hidden completely from view at the critical points. The walled cutting that hides it through the rest of the town leaves no room for platforms, so the station is away to the west where the tracks reach ground level. A second station, for a now closed line to the south, was several streets from the centre and kept far from all the important buildings.

The LCC’s first draft, drawn up just before their abolition in 1965, was for a dual carriageway running through Greenwich Park in open cutting. A couple of footbridges would link paths on either side of the road, and ramps would lead down to bus stops. It would scythe through existing shops and houses both east and west of the park, with a big new one way system around the market and a link road bypassing the High Street by obliterating most of the buildings on its north side.

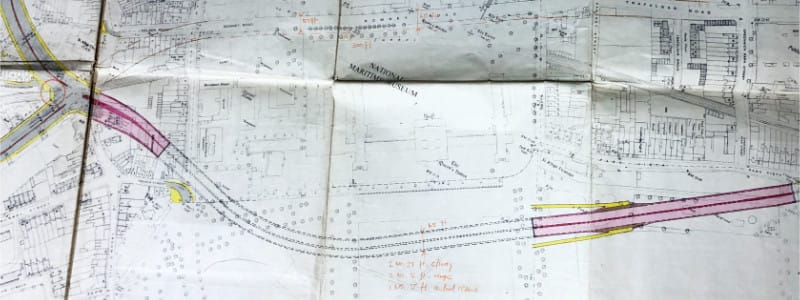

The Greater London Council took over the work and produced a revised design in 1967, which attempted to mitigate the worst excesses of the original: it would now use two lengths of tunnel to cross the park, though would still be in cutting for part of the way; it also used more existing street alignments in the west to leave the High Street and market intact.

This plan still seemed extraordinarily unlikely to succeed, given the need to tear up Greenwich Park and only restore part of the greenery afterwards. But it persisted for several years, and in 1969 the GLC was still referring to a bypass, “probably” in tunnel under the park, as an eventual solution.

Going to the Dogs

It is fair to say that nobody was happy with the bypass plan, and even the GLC couldn’t bring themselves to fix its line or protect it from development. Instead, they did what they’d done with other intractable problems on London’s road network: just like the South Cross Route at Blackheath, and Ringway 3 in north west London, they asked Colin Buchanan to fix it. Buchanan had written the hugely influential report “Traffic in Towns” and was now considered the foremost expert in urban highway planning.

His Greenwich and Blackheath Study was published in 1971, and was entirely novel. Greenwich and its rarefied surroundings would be left alone, to the extent that it would become a “tourist enclave” with all through traffic banned. It would sit in the middle of a box of new routes, making it an island “to stop it choking to death”.

To the south, the A2 would be improved and placed in a deep cutting across Blackheath to hide it from view. To the west, through traffic could use an improved A2209 and A200. To the east the Ringway 1 East Cross Route was an effective barrier. And to the north, two new bridges would carry a new Greenwich bypass across the Thames twice, using the Isle of Dogs as a stepping stone.

The Isle of Dogs at this time was a blank canvas ready for redevelopment: the traditional docks were dying out, but few plans had been made for its future. Nobody yet knew that it might become a commercial hub of towering skyscrapers, so in 1971 it was just a useful place to dump a relief road.

Buchanan also wanted other changes, including a new park and ride facility at Kidbrooke, and the extension of the tube through Greenwich to reach it. There would be a local bypass for Blackheath Village and a host of traffic restrictions, banning heavy lorries and prioritising buses.

Buchanan’s scheme was both ambitious and expensive. He envisaged most of the work happening by 1981 - a very fast turnaround for a scheme only just sketched out for the first time - and everything completed by 1991.

It was unlikely that everything on this new, expensive and difficult shopping list would be completed, but it also came just two years before the grand bonfire of all London’s road plans in early 1973.

No reference can be found to the study’s recommendations ever being officially accepted. It’s assumed they vanished along with all the rest, and either way Greenwich today remains unbypassed - a mixed blessing, since it continues to suffer heavy traffic, but it also remains gloriously and beautifully intact.

Sources

- Route of 1965-1969 bypass proposals, Deptford-East Greenwich; pressure for improvements; lobbying by RFAC; GLC did not publish or fix line: MT 106/295.

- Greenwich and Blackheath Study and recommendations: Langton, R. (1971) "£71m Life-Saver for Choked Greenwich", Evening News, 6 April. Available at MT 106/299.

Picture credits

- Photograph of Old Royal Naval College skyline is taken from an original by Oxyman and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Photograph of Queen's House from the Observatory is taken from an original by Jim Osley and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of the University buildings is taken from an original by Paul Gillett and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- 1967 bypass plan is extracted from MT 106/295.

- 1971 Buchanan plan appeared in Langton, R. (1971) "£71m Life-Saver for Choked Greenwich", Evening News, 6 April.

- Photograph of Nelson Road is taken from an original by Colin Park and used under this Creative Commons licence.