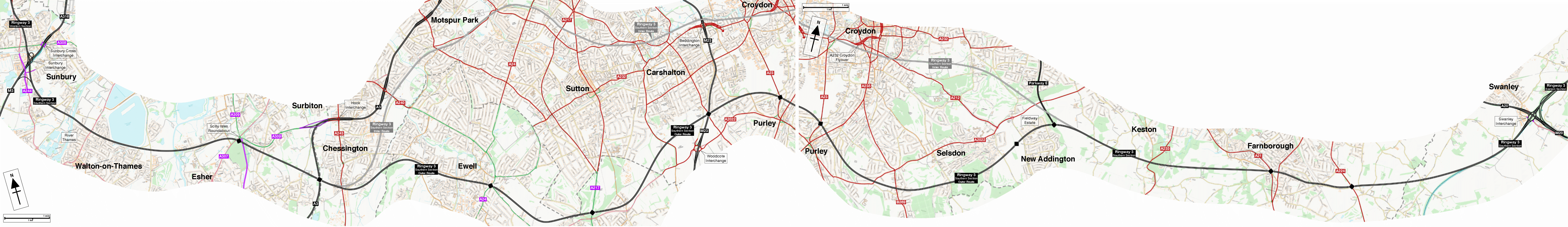

Sweeping through the suburbs from the M20 in the east to the M3 in the west, skimming the centre of Croydon and squeezing past Epsom races: the southern side of Ringway 3 would have been enormously destructive and intrusive, and yet it was never the subject of much protest.

There's a very good reason for that: nobody knew where it was going to go. Ringway 3's Southern Section was never, as far as anyone can tell, narrowed down to a single route.

That's not to say that no routes existed. Abercrombie sketched a line for the "D" Ring Road, his predecessor to Ringway 3. Later, studies were made to examine some alternatives, and in the end the options were pared down to just two possibilities. One skirted around the fringes of the urban area, passing through the suburbs here and there; the other was more decidedly urban, passing almost through the centre of Croydon.

When the Ringways were cancelled and the engineers were told to put down their slide rules, the study hadn't reached a point where it could recommend one route or the other. The result is that we have two lines for this motorway between Addington and Epsom, and only basic hints about interchanges.

Given that limitation, this account is based on an educated guess, as follows. The inner route, via central Croydon, would have been hugely controversial. By the time it was being evaluated, the Department of the Environment (DoE) would have been only too aware of the widespread protests and visceral anger caused by Ringway 2's Southern Section just a few miles to the north. They would be unlikely to want to go through the same process themselves. They were also, at the same time, abandoning an urban route for Ringway 3 in north west London in favour of an easier, more rural line around the outside.

Our guess is, therefore, that if this section of Ringway 3 had made it further through the planning process, it's very likely the DoE would have been inclined to select the outer route. That is the one we present below, with the addition of junction locations from an earlier GLC route study, though a description of the inner route is also provided.

Outline itinerary

Continues from Ringway 3 Eastern Section

M20 and A20 (Swanley Interchange)

A21 Farnborough Way

Local connections to Addington and Hayes

Parkway E

Local connections to Purley and the A23

M23

A217 Brighton Road

Local connections to Ewell and the A24

A3

River Thames

Local connections to Shepperton

M3 (Sunbury Interchange)

Continues as Ringway 3 Western Section

Cost summary

| Property acquisition (1970) | £19,220,000 |

| Construction (1970) | £82,514,500 |

| Total cost at 1970 prices | £101,734,500 |

| Estimated equivalent at 2014 prices Based on RPI and property price inflation |

£819,230,137 |

See the full costs of all Ringways schemes on the Cost Estimates page.

Route description

This description begins at the eastern end of the route and travels west.

Swanley to Carshalton

Continuing from the Ringway 3 Eastern Section, the motorway would interchange with the M20 and A20 at Swanley and then curve south-west, off the line of the modern M25, meeting the A224 Court Road just north of the village of Chelsfield. From here through to Addington, the motorway would follow a line protected for years by Kent County Council for a "Farnborough-Croydon Link Road".

It would follow the north side of Warren Road, crossing the railway at Chelsfield Station, and then passing through the suburbs along a vacant corridor of land, since infilled with houses, through what is now Goldfinch Close and Osgood Avenue. A second interchange would connect to the A21 Farnborough Way just north of the roundabout with the B2158 Farnborough Hill.

Gentle curves would carry the motorway through the undulating countryside south of Keston, crossing the A233 Westerham Road near Holwood Park and passing south of Nash. Reaching the northern edge of New Addington, the vast housing estate on the edge of Croydon, an interchange would form the terminus of Parkway E, travelling away towards Brixton through the suburbs. From here the inner route option branches off towards Croydon town centre.

The outer option, however, turned south west through what is now the Fieldway Estate. Crossing Addington Court Golf Club, a local junction would serve New Addington and the A212 towards Croydon. Ringway 3 would pass around the southern edge of Selsdon, crossing the B269 Limpsfield Road on the site of the modern Waitrose supermarket. It would cross the A2022 Rectory Park before cutting through Hyde Road and Westfield Avenue at an oblique angle, destroying many houses.

The next section would cut an arbitrary line through pleasant suburbs, crossing Riddlesdown Road, the Brighton Main Line railway and the A235 Brighton Road to reach an interchange with the A23 Purley Way. A curve to the west would lead to another destructive cut through South Beddington to reach a major interchange with the M23 at Woodcote Green.

Beddington to Sunbury

A relatively easy run along the north side of the A2022 would bring Ringway 3 to a junction with the A217 Brighton Road, at the edge of Banstead Downs, before turning north west and entering Ewell. Another junction would connect to the A24 Ewell Bypass. Cutting against the grain of the street pattern south of Ewell town centre, the motorway would cross Epsom Road and West Street before joining the south side of the B2200 Chessington Road and curving around the southern edge of Chessington itself. The inner route option rejoins the outer route at this point.

Turning north-west again, an interchange with the A3 Epsom Bypass is followed by a straight run to the Scilly Isles roundabout, where the motorway would link to the A307 and A309 for Kingston. Squeezing into a narrow corridor of land between Epsom Racecourse and the railway, a vacant line existed in the 1960s along the southern edge of the Queen Elizabeth II Reservoir, now built over, which led to a crossing of the Thames alongside River Walk.

The motorway would turn north again, meeting the M3 at Sunbury Interchange, immediately east of the A244 Upper Halliford Road. Connections would be provided with the M3 to the west, but not towards London. Ahead would be the Ringway 3 Western Section.

Another way

The description above follows the more likely outer route for Ringway 3. The inner route was quite different, and far happier to simply bulldoze a line through the suburbs.

From New Addington, it would pass through Upper Shirley, crossing Upper Shirley Road next to the High School and cutting across the middle of Lloyd Park. The route through Croydon was direct to the point of absurdity, pushing an almost straight path over Coombe Road and the Brighton Main Line railway, crossing the A235 South End somewhere around the Skylark pub and brushing aside houses and residential streets to reach Duppas Hill Recreation Ground. That too would be sliced in half by the motorway.

Ringway 3 would cross the A232 Duppas Hill Road and the A23 Purley Way just north of Waddon station, and then cut diagonally through a series of north-south streets from The Ridgeway to Bridges Lane, meeting the M23 near Carew Manor School on the edge of Beddington Park.

A line is then drawn straight through Carshalton, crossing the B278 West Street just north of the station, cutting through Royston Park and the houses on Greenhill and Woodend, and reaching the A217 Reigate Avenue alongside the railway bridge south of Rose Hill. A cut through a few more suburban streets would then lead to the A24 Epsom Road and a run through the southern edge of Morden Park.

Turning west, the motorway would run along the edge of Morden Cemetery to follow Green Lane, crossing the railway at Broadmead Avenue and joining the south side of the Chessington Spur railway line as far as Tolworth - where the motorway would be running virtually alongside the A3 Kingston Bypass. Turning to the south, Ringway 3 would skirt the edge of Chessington, rejoining the outer line as it crossed the A243 Leatherhead Road.

A matter of priorities

In the 1940s, Abercrombie drew in a fully circular "D" Ring Road, but after the war the Ministry didn't see the need for all of it. They added the west and north sides to the trunk road programme, and abandoned the rest.

Twenty years later, though, expert opinion had swung the other way, and the southern side of the "D" Ring was resurrected. That was a problem: in the intervening years, Abercrombie's line had not been protected from development, and his route was no longer viable. A new line was needed.

The Greater London Council only came into existence in April 1965, but they had already launched a route study for the southern section of Ringway 3 by the end of the year. They considered Abercrombie's line and a range of alternatives, including some much further in towards London and one that, rather improbably, passed through the Royal Parks. In the end they settled on a line that borrowed the Farnborough-Croydon Link Road and then skirted around the built-up area south of Croydon and Sutton - roughly the outer line described above.

Having accepted responsibility for other parts of Ringway 3, it was always likely that this project would also be handled by the MOT, and indeed the Ministry was where the GLC's route study ended up. But in August 1966 they were struggling with it.

Documents from that era suggest that the Ministry agreed that there was a clear case for it - one memo from 1966 refers to the "strong and urgent need" for it because east-west communications in South London were so poor. But they were unable to do much about it because - for some reason not known even to them - the London Traffic Survey had omitted from its forecasts the length of Ringway 3 between the M3 and A3. That put all the traffic counts across South London out of kilter, and without useful traffic figures, they couldn't proceed.

The impasse was broken in August 1969 when the MOT handed the problem over to Brian Colquhoun and Partners, a firm of consulting engineers, and asked them first to investigate the demand for the road (to make up for the missing LTS data) and then recommend a line for it. Their remit covered the whole length from the A20 to the M3.

Pieces of the jigsaw

The work of the study was done rather quietly - and deliberately so. In 1969, when the study started, angry protests were already taking place against the southern section of Ringway 2 - another urban motorway project pushing its way through South London just a few miles away. Nobody wanted to stir up the same trouble from residents along the line of Ringway 3 if they could possibly avoid it.

Their secrecy became a whole new problem. It was common knowledge that the Ministry had engineers plotting out motorway lines around Croydon and Sutton: the launch of the feasibility study was marked with plenty of news coverage, and the much-publicised Greater London Development Plan, shortly to go to public inquiry, made plain that the GLC required a major motorway ring road somewhere in the area. The question was, where?

Frustration was vented at the GLDP Inquiry, where objections were raised against a motorway that was, so far, little more than a rumour. One of them was particularly noteworthy. Inquiry papers list an objection lodged by "The Mayor, Aldermen and Burgesses of the London Borough of Sutton", represented by the Town Clerk and the Chief Planning Officer.

They found it surprisingly easy to poke holes in the GLC's masterplan. The GLDP covered a ten-year period, but - they argued - if no line had been chosen for the south side of Ringway 3, it couldn't possibly be built before the early 1980s and therefore did not belong in the plan. They also pointed out that the GLDP gave no indication what purpose it would serve. If it served no definable purpose, it was unnecessary.

Worse, people were suffering the effects of planning blight because there was already enough information in various GLC publications to guess the route.

"By relating figure 2.2 in 'Movement in London' to figures 3.6, 4.3 and 5.4 three alternative routes can be deduced which are well within the boundaries of the Borough. By carrying out this simple exercise many people were able to substantiate that their property was in the vicinity of a possible route for Ringway 3."

All those figures showed vague, theoretical lines for the purpose of traffic modelling, but that wasn't the point. People were drawing conclusions from whatever information they could find and the damage was real. Secrecy was not working.

Problems in Sutton came to a head in July 1970 when the Sutton & Cheam Advertiser published a map claiming to show the route of Ringway 3 passing through the Borough. No such thing existed, of course. The newspaper's journalists had found a diagram of the overall network pattern for London - showing a dotted line for Ringway 3 that was little more than a circle around London - and then plotted that line on a detailed street map of the borough. It was hopeless guesswork. But it didn't matter: their amateur sleuthing resulted in hundreds of phone calls and letters to the Borough Council from terrified residents.

Sutton's final argument was that the GLDP declared the South Orbital Road "less urgent than the establishment of the primary road network including Ringway 3", but in attempting to make this its official policy, the GLC was entirely divorced from reality. The South Orbital Road - now the M25 through Surrey - was about to start construction. With bulldozers moving in on that project, a line fixed for Ringway 2's Southern Section to the north, and Ringway 3 barely a twinkle in the planner's eye, how could it possibly go in the plan?

The panel agreed. Their recommendation, made when the Inquiry finally closed, was that Ringway 3's Southern Section should be abandoned because the South Orbital was under construction and served exactly the same purpose.

Unfinished business

The drama of the Inquiry took place as Brian Colquhoun and Partners got on with their work. Their first task, of course, was to come up with new traffic forecasts, something that was easier said than done.

Three sets of traffic survey figures were available: the London Traffic Survey itself, the M25 Survey and the South Orbital Road Survey. All three were examined and found to be totally and hopelessly incompatible, so the LTS survey alone was used, and new computer models built to re-run the forecasts, this time with all of Ringway 3 included.

By May 1970, with that settled, the first results emerged and they are surprising even today. Comparing the two possible routes, the engineers found that the inner route would require four lanes each way, and if it were built, Ringway 2 would be "heavily loaded". The outer route would attract enough traffic to justify three lanes each way, but would leave Ringway 2 "loaded considerably in excess" of its four-lane capacity. The demand for the road, in other words, was astonishing.

The figures also showed that, even if the outer route were built, only minimal amounts of traffic would be drawn away from the Ringway 4 South Orbital Road, so the case for building both motorways was entirely clear-cut. That was starkly in contrast to the claims of those fighting the project at the GLDP Inquiry, who thought one road would make the other redundant, but the figures were never made public.

That level of secrecy even applied to other transport studies being carried out in the same area. Consultants working for the Department of the Environment (as the Ministry had become) to plan a futuristic "hover train" between Heathrow and Gatwick Airports requested some information about proposed lines for Ringway 3, but Colquhoun and Partners were sternly told that they must not be given anything of the sort.

Alignments most certainly existed, though. Based on the two lines under consideration, all sorts of minor variations and options were drawn up. By May 1970, 335km of route had been plotted out in detail at 1:2500 scale - a huge figure considering that the finished road would only be about 60km in length - and by February 1971 the figure had risen to 450km. Preliminary interchange designs were produced too. None of these drawings, sadly, appear to have survived.

It was known that the western half of the route would have four lanes each way and would be an urban motorway, designed for speeds of 80km/h (50mph), while the eastern half would have three lanes each way at 120km/h (70mph). But nobody could decide where the road would transition from one to the other. For the time being, it happened at a map grid line near Croydon. "Preliminary" was the operative word.

With hundreds of variables and unknowns still to be resolved, Colquhoun and Partners issued an Interim Report on Ringway 3's Southern Section in summer 1971, but their full report was pushed back further and further as their terms of reference were amended and the work proved ever more difficult. In the end, events overtook them: the Layfield Report was published, rendering the south side of Ringway 3 obsolete, and their work was halted.

Today, we are left with no final report, no drawings, no junction layouts, and no real idea which of the two routes would have been selected. Ringway 3's Southern Section will likely remain forever a mystery.

Sources

- Lines of inner and outer routes, as studied 1969: MT 120/231.

- GLC route study and GLC-preferred interchange locations on outer line: MT 106/293.

- This length of "D" Ring Road abandoned during 1950s: MT 106/293.

- MOT agree strong case for road, LTS omits M3-A3 section of R3: MT 106/413.

- Colquhoun and Partners brought in; terms of study: MT 120/231.

- Traffic forecast problems; results of forecasts: MT 120/232.

- Hover train correspondence; lengths of route plotted out at 1:2500 scale; width of road changes at grid line; interim report published, no final report: MT 120/272.

- LB Sutton objection to GLDP: HLG 159/1318; MT 120/250.

- Layfield Panel recommendation for R3: MT 120/284/1.

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Plan showing two lines for Ringway 3 extracted from MT 120/231.

- Plan showing blue and orange routes across South London, GLC 1965 Route Study and 1964 traffic flow forecast extracted from MT 106/293.

- Photograph of Fieldway Estate taken from an original by David Anstiss and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of the Thames at Walton taken from an original by Alan Hunt and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Abercrombie line for "D" Ring extracted from Abercrombie, Patrick (1944). Greater London Plan. London: University of London Press.

- 1972 Primary Road Network map, with R3 South missing, extracted from HLG 159/479.

- Photograph of Wrythe Green taken from an original by Dr Neil Clifton and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Clipping from Sutton and Cheam Advertiser is extracted from MT 120/250 and originally appeared on 23/07/70.