A critically important link in London's proposed urban motorway network, connecting the M4 at Chiswick to central London and completing the Ringway 2 circuit - but fierce opposition from the locals made the GLC scared to ever reveal its route.

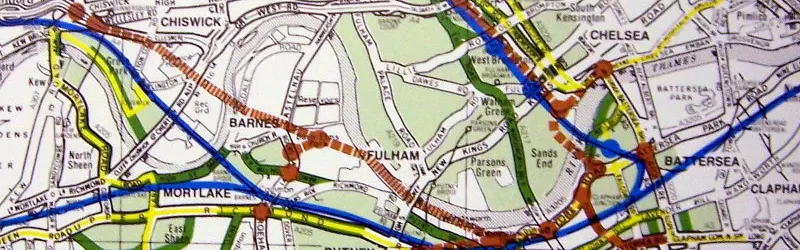

The western side of Ringway 2 started life as a proposal from the former London County Council in the very early 1960s, at a time when only one motorway ring road was planned. The London Motorway Box - later Ringway 1 - would have had radial motorways in all directions, and one of them ran alongside railway tracks through Putney and Barnes to reach the M3 and M4. When the Greater London Council arrived and started planning more ring roads, this "Basingstoke Link" became part of Ringway 2, intended to serve orbital traffic as well as linking the M3 and M4 to the Box.

Unlike many of the GLC's other motorway plans, this section of Ringway 2 was not going to pass through districts of tired, low-rent buildings or areas of planned slum clearance. To make the connection between Wandsworth and the North Circular Road, it would pass through Putney, Barnes and Chiswick - affluent suburbs full of settled home owners, members of the middle classes who kept up to date with current affairs and a keen eye on their house prices.

Because of that, some of the most vocal and spirited grass roots groups sprung up in this part of London specifically to oppose this length of Ringway 2. The GLC took the extraordinary decision to pretend there was no fixed line for the road through Barnes until after the GLDP Inquiry had endorsed the rest of the motorway and its construction became inevitable. In the end, of course, the GLDP Inquiry did not endorse the motorway, and the GLC's leadership had themselves abandoned it anyway.

The official route for Ringway 2 was not difficult to guess at the time. Plans showed a gap in the motorway's line and a pair of arrowheads pointing vaguely towards each other from either side of Barnes, and few were fooled by the ploy.

The route of Ringway 2's Western Section as described below comes from highly secretive plans produced by the GLC in the late 1960s, and which the documentation shows they chose not to publish in an attempt to keep a lid on the public's anger. This might actually be the first time the official route has been described with certainty, outside of a few secretive GLC planning meetings half a century ago - though in practice it's actually no different to the route everybody had suspected all along.

Outline itinerary

Continues to Ringway 2 North Circular Road

M4 and A4 (Chiswick Roundabout)

M3 or A316

River Thames (Barnes Bridge)

Possible connection to A306 Rocks Lane

A3 and Ringway 2 Clapham-Wandsworth Link

Continues from Ringway 2 Southern Section

Cost summary

| Property acquisition (1970) | £16,400,000 |

| Rehousing (1970) | £4,400,000 |

| Construction (1970) | £23,700,000 |

| Environmental works (1970) | £945,000 |

| Total cost at 1970 prices | £45,445,000 |

| Estimated equivalent at 2014 prices Based on RPI and property price inflation |

£698,944,991 |

See the full costs of all Ringways schemes on the Cost Estimates page.

Route description

This description begins at the southern end of the route and travels north.

Beginning in Wandsworth, and continuing west from Ringway 2's Southern Section, the Western Section would depart Wandsworth Interchange by joining the north side of the rail line from Waterloo towards Richmond - a four-track railway known as the "Windsor Lines". All the houses on the south side of Disraeli Road and Norroy Road would have been demolished to make way for the motorway, while the houses on the north side of those streets would only have been saved if a way were found to build a retaining wall to support them from below, and the street itself was then projected out above the motorway. That's what an ambitious set of engineering cross-sections from 1965 show, but it would be a formidable engineering challenge and perhaps the more likely outcome (especially considering much cheaper 1960s property prices) would simply be to demolish the lot.

Continuing west along the railway, the motorway would follow the south side of Clarendon Road and Dryburgh Road, emerging from its cutting to run at ground level. Here, long back gardens meant the houses themselves might have been saved, but dining rooms and kitchens would have looked out on to the hard shoulder.

The motorway would then run through Barnes Common, adjacent to the railway station, and join the north side of the railway towards Hounslow. Plans here vary; in 1965 the motorway was planned to simply run at ground level, but in later years (as the opposition to the motorway became more apparent) there are suggestions that it might have been placed in cut-and-cover tunnel below the Common. Some documents refer to the possibility of a local interchange with the A306 Rocks Lane but this seems not to have been part of the official proposals.

From this point to the A316, official plans released to the public showed a gap in the route, with a pair of arrowheads vaguely pointing to each other across Barnes. But a route, described below, did exist, and was officially safeguarded from development in 1965. By 1968 there were detailed engineering drawings of it. In mid-1969, a route study considered a different line, running along the south side of the Thames through Mortlake and Kew, but that was rejected as being worse in every possible way, and the safeguarded line was endorsed once again. Still the secrecy was maintained, with the GLC insisting in public that it was "under investigation". Then, in July 1970, knowing just how controversial the motorway slicing through Barnes would be, a meeting was held to discuss the route. It was decided that the official line - which was not really under investigation and had been fixed for five years by that point - would remain secret until the conclusion of the GLDP Inquiry.

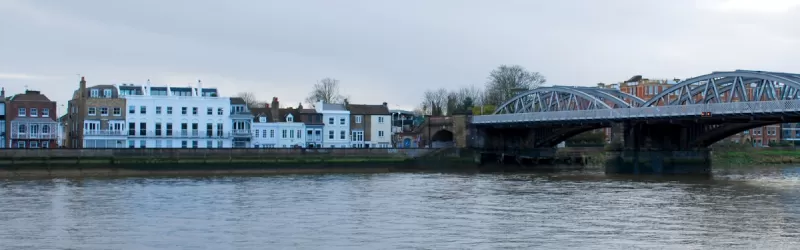

Through Barnes, the west side of Cleveland Gardens would be lost, and where it crossed Barnes Terrace - a street of colourful historic buildings lining the riverfront - two Georgian Houses, numbers 13 and 14, would be dismantled and relocated. The motorway would then cross the Thames adjacent to the railway bridge, taking a slice off the sports fields to reach the A316 Great Chertsey Road at Duke's Meadow. Running at ground level, the motorway would pass beneath the A316, which is raised up to cross the railway. Some plans show a three-level stacked roundabout interchange here, with the roundabout above both roads, but the final design appears to be a free-flowing junction with some sliproads passing below the railway and motorway and others above.

Streets and houses immediately north of the railway line through Chiswick would be lost, with the motorway beginning to curve towards the north-west around Whitehall Park Road. This curve would allow it to meet the North Circular Road just north of Chiswick High Road and the A4.

The exact shape and form of the interchange between Ringway 2 and the M4/A4 does not appear to have ever been fully settled. The standard procedure at the time was for the Ministry of Transport to take responsibility for interchanges with trunk roads - and the M4 was a trunk road, so that would ordinarily make it their problem. But unusually, the Ministry and the GLC agreed that Chiswick Interchange would be the GLC's responsibility. The GLC, accordingly, drew up some plans, but no decision on a final layout was recorded. The one shown on the map above is from the 1969 route study.

Of the three plans that have come to light, two see Ringway 2 passing over or under Chiswick Roundabout and appear in material supplied to the GLDP Inquiry panel to support objectors' statements, and their origins are obscure. However, written descriptions of Ringway 2 in this area invariably mention that it would pass east of the roundabout, joining the North Circular Road at the eastern edge of Gunnersbury Park, so the most likely scheme was the third, which appears in a GLC planning document. It sees the motorway passing east of the junction, on the line of Silver Crescent, with sliproads woven through the surrounding urban area, mostly following looping and curving railway tracks.

North of the interchange, Ringway 2 would join the North Circular Road, completing the circuit around London.

The Chiswick triangle

The late 1960s were not a time to be a resident of Chiswick. A suburban district of pleasant semi-detached houses and prosperous families lay between Hogarth House and the Thames, but its attractive location put it in the firing line. It lay between a number of other places where a motorway would be much more difficult to build, it had the A4 and A316 already passing through, and a convenient railway line alongside which Ringway 2 could run. The unfortunate result was that, between the Ministry's intention to upgrade the A4 and A316 to major dual carriageways, and the GLC's plan to build its ring road beside the railway, the entire suburb was set to be carved up to make space for a huge motorway interchange complex.

Some fragments of suburbia would remain: a sliver between the railway and river, a little shard near the Hogarth Roundabout, a slice north of the A4 pressed up against the Chiswick High Road. And, in between, a triangular island of houses hemmed in by thundering motorways on every side. Campaigners named it the Chiswick Triangle and life inside it looked pretty horrifying if all the road plans came to fruition.

Across the capital, pressure groups made the case to the GLC and, later, the GLDP Inquiry panel that their peaceful suburb would be forever ruined by the imposition of a new motorway. But the Chiswick Triangle was a horror story to outstrip any of them. Local campaigners worked extraordinarily hard, becoming self-taught experts in the new and emerging practices of noise profiling and environmental standards, providing figures - and evidence for them - that were more detailed than anything the GLC had attempted.

Residents' groups produced diagrams to demonstrate how the whole area within the triangle would be within a "nuisance zone" of noise and fumes that occurred within a certain distance of a major road, making a leafy and pleasant suburb significantly less pleasant. Some of their estimates suggested that more than half of the neighbourhood south of the A4 would be demolished to make way for the motorways and their junctions, and what remained standing would be effectively unfit for habitation. It was not a vision of London's future that many people were comfortable to accept.

History repeating

Finding a route for an eight-lane motorway through some of West London's wealthiest suburbs was never going to be an easy task, and the reaction of the residents who would have to suffer it was no surprise. When the motorway through Barnes and Chiswick was cancelled in 1973, there was relief that their homes and surroundings had been preserved for posterity.

It must have come as a surprise, then, when new plans to improve London's roads arrived in the late 1980s. Just fifteen years after Ringway 2 was scrapped, it was rearing its head again. The West London Assessment Study, published in 1988 by consulting engineers Halcrow, considered ways to address chronic traffic problems around Barnes, Wandsworth and Fulham, including road improvements and better public transport facilities. Halcrow found that the best return on investment was offered by the construction of a high quality expressway route from the end of the M4, through Chiswick and Duke's Meadows, across the Thames and Barnes Common to reach the A205 South Circular Road at Red Rover junction. From there, traffic would disperse onto the Lower Richmond Road towards Putney, the South Circular itself and Roehampton Lane towards the A3. This was the same report that also recommended the Western Environmental Improvement Route, a reworking of the Ringway 1 West Cross Route.

The outcry from locals was just as sharp and indignant as before. Recognising a losing battle, the engineers thought again, and the final outcome of the study instead recommended new railway and bus services along with a new road in a deep bored tunnel. It would have run roughly on the line of Ringway 2 between Chiswick and Wandsworth, but entering tunnel just south-east of the M4, passing beneath Chiswick, the Thames and Barnes, and surfacing just long enough to interchange with a spur road towards Barnes and the A205 before going back underground. It would then run east underneath the Thames all the way past Putney, finally emerging on the waterfront at Wandsworth.

This tunnelled road might have made things better on the parts of the South Circular it bypassed, but it would have been an astonishingly expensive way to do it. In 1990, with local elections fast approaching and opposition to the road plans continuing to mount, the Transport Minister Cecil Parkinson cancelled the tunnel scheme, and with it any prospect of Ringway 2 returning to West London.

Sources

- LCC proposal for "Basingstoke Link"; alignment Wandsworth-Chiswick: GLC/TD/DP/LDS/02/097.

- GLC decide not to reveal line until after GLDP Inquiry: GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/061.

- Plans showing gap in line; safeguarded line; free-flowing interchange with A316; GLC assume responsibility for A4/M4 interchange: ACC/3499/EH/08/04/020.

- Engineering drawings made by 1968: some exist at GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/049.

- Route study with rejected option via Mortlake in 1969; three-level stacked roundabout at A316: GLC/DG/AR/6/093.

- Chiswick campaigners on noise profiling and environmental impact: HLG 159/2274, HLG 159/2342.

- West London Assessment Study proposals; Tunnelled road from Chiswick to Wandsworth: Sir William Halcrow & Partners Ltd. (1989). West London Assessment Study: Stage Two: Tackling the Problems: A Summary of the 'Report on Options' London: Department of Transport.

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Plan with gap in Ringway 2 and arrows pointing to Barnes extracted from HLG 159/1286.

- Route study plan from July 1969 extracted from GLC/DG/AR/6/093.

- Artist's impression of view from Barnes Bridge taken from a newspaper cutting, undated and uncredited, held at Richmond Local Studies; from context it appears to be the Richmond Herald circa 1969.

- Plan of part-tunnelled route from Chiswick to Wandsworth extracted from Sir William Halcrow & Partners Ltd. (1989). West London Assessment Study: Stage Two: Tackling the Problems: A Summary of the 'Report on Options' London: Department of Transport.

- Noise profile map of Chiswick extracted from HLG 159/2342.