This page is about abandoned proposals to incorporate the A3 into an urban motorway network for London. Information about the road as it exists today is in the Motorway Database.

The A3 has been one of London's most important approaches for centuries. Most of its planned improvements were built, making a very fast road that fizzles out at Wandsworth.

Before it was the A3 it was the Portsmouth Road, a coaching route from the nation's capital to its Navy. Its importance was recognised at the dawn of the motor age, and some of the earliest motor-era bypasses in the UK opened later the same decade of the A3.

Work continued throughout the twentieth century, with upgrades to near motorway standards, and into the twenty-first, with the Hindhead Tunnel finally completing a continuous dual carriageway from London to Portsmouth. But within London, the A3 slogs its way through Wandsworth, Clapham and Kennington to reach London Bridge. Nobody in their right mind would try to rebuild all of that.

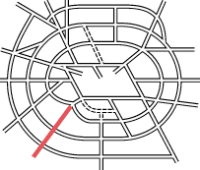

Because of that, the plan for the A3 in the Ringway era was for a vastly upgraded road to reach, and end on, Ringway 2 in Wandsworth. Its terminus would be a sprawling interchange where traffic could disperse onto the new ring road or continue forward on the Clapham-Wandsworth Link, an urban motorway that joined up with Ringway 1. The rest of the A3 from Wandsworth to the City was to remain a Secondary Road in the GLC's masterplan.

Take a look at the A3 today and you will see almost a motorway from the Surrey countryside to Putney Heath, where it peters out within spitting distance of Wandsworth. If you're looking for a Ringways-era road that's almost finished, this might be it.

But Ringway 2 never arrived, and nor did the Clapham-Wandsworth Link, or that sprawling terminal junction. Without them the last piece of the jigsaw, extending the A3's high speed run down West Hill to the finish line, remains unbuilt. Instead the road narrows from three lanes to one with a jolt, and the all-day traffic jam from there to the Wandsworth one-way system is a permanent reminder of the folly of building a full-blown Ringway radial without a Ringway to take its traffic.

Outline itinerary

R2 Southern Section, R2 Western Section and R2 Clapham-Wandsworth Link (Wandsworth Interchange)

A219 Tibbet's Ride (Tibbet's Corner)

A306 Roehampton Lane

A308 Kingston Vale (Robin Hood Gate)

A238 Coombe Lane (Coombe Lane Interchange)

A298 Bushey Road

B282 Burlington Road (Shannon Corner)

A2043 Malden Road (Malden Junction)

A240 Kingston Road (Tolworth Interchange)

A243 Hook Road (Hook Interchange)

R3 Southern Section

A244 Copsem Lane (Esher Common Interchange)

A245 Byfleet Road (Painshill Interchange)

R4 South Orbital Road (Wisley Interchange)

Continues to Guildford and Portsmouth

Cost summary

| Property acquisition (1970) | £2,000,000 |

| Construction (1970) | £7,450,000 |

| Total cost at 1970 prices | £9,450,000 |

| Estimated equivalent at 2014 prices Based on RPI and property price inflation |

£85,237,261 |

See the full costs of all Ringways schemes on the Cost Estimates page.

Route description

This description begins at the south-western end of the route and travels north-east.

Wisley to Wandsworth

Almost the whole of the A3's route can be driven today, and large parts of it exist just as planners envisaged in the Ringway era. Entering London from the south west, a three-lane dual carriageway from Guildford would meet the Ringway 4 South Orbital Road at Wisley Interchange, a major junction on the site of modern day M25 junction 10.

At Painshill, the A3 would branch off its original line to form the Esher Bypass, a road designed to full motorway standards. An interchange at Esher Common would meet the A244 Copsem Lane, and also a dual carriageway running north to the Scilly Isles roundabout. The link road was never built and this is why the modern A3 has no sensible connection to Kingston from the south.

At Hook, the road would meet Ringway 3's Southern Section, and then turn sharply east to join the line of the 1920s-era Kingston Bypass, rebuilt to provide three lanes each way at 70mph. Service roads on each side would cater to the houses and businesses alongside.

Underpasses then follow at Hook, Tolworth and Malden, before a length of elevated road carries the A3 over a complex junction at Shannon Corner. A free-flowing connection would lead to the A298 spur road towards Raynes Park. At Coombe Lane the complex junction is almost a complete cloverleaf interchange.

The Kingston Bypass finishes at Robin Hood Gate, the south eastern corner of Richmond Park, where the A3 returns to its ancient alignment. Many of the houses here would be swept away for a large roundabout with a curving flyover to carry six lanes of traffic over the top. The A3 would then run non-stop up the hill to Putney Heath.

The signalised T-junction with the A306 Roehampton Vale was brand new in the mid-1960s and no plans were developed for a flyover or underpass here, but one may have been built later if the rest of the A3 had been completed. A two-lane underpass then carries the A3 under Tibbett's Corner roundabout.

From here the six-lane road would continue down West Hill, either by widening the existing A3 or building a new road close by, and a junction would provide access to the A205 Upper Richmond Road. The road would terminate at Wandsworth Interchange, a large free-flowing junction of unknown layout located near Armoury Way on the north side of Wandsworth town centre, giving access to Ringway 2's Western and Southern Sections and the Clapham-Wandsworth Link.

A road fit for a Kingston

London's road to Portsmouth was always of great importance, but it was always slow and impractical because it took the traveller through the ancient streets of Kingston and Guildford. Bypasses for both were among the earliest priorities for new roads at the beginning of the twentieth century.

A bypass for Kingston-upon-Thames was first proposed by the Board of Trade in 1911 and approved by the Arterial Road Conferences in 1914, as part of a series of ideas promoted by Colonel R.C. Hellard, one of the new century's roadbuilding pioneers. As a result the first major improvement was planned a good eight years before the road even became the A3, but the outbreak of war put a halt to it for most of the next decade.

Work eventually began under the brand-new Ministry of Transport in 1923, and the Kingston Bypass was officially opened by the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, on 28 October 1927.

It was a particularly fine road. A corridor 100 feet (30m) wide had been cleared from Richmond Park to Sandown Park Races near Esher, a distance of more than eight miles. On it, engineers had built a concrete road 30ft wide, flanked by generous verges and footpaths on both sides, with the intention that conversion to dual carriageway would be trivial.

It ran through open countryside, but that didn't last long. Before the 1920s were out, the brand new bypass bristled with semi-detached houses and roadside businesses: Surbiton, Tolworth and Malden were rapidly suburbanising, thanks to speedy electric railways to London and easy motoring to the city and countryside on the A3.

Many houses filled the gaps between towns and villages, but bigger profits were to be found building houses on the bypass itself, since the road was already built. No planning controls existed to stop it, so Kingston's brand new bypass was immediately strangled by suburban development.

When the new 30mph urban speed limit was introduced in 1934, the Bypass was at serious risk of being subjected to it because of the almost continuous development. A decade later, as Sir Patrick Abercrombie drew up plans for London's post-war rebuilding, he considered it a lost cause, and suggested an entirely new road almost alongside as an alternative.

Tied up in ribbons

In 1935, the Government passed the Restriction on Ribbon Development Act, finally giving local authorities the power to prevent builders from lining new major roads with houses.

It came too late for the A3, so the only solution was to improve the existing road. By the early 1960s the Kingston Bypass had been dualled from the Scilly Isles roundabout near Esher to Shannon Corner, where it branched in two. That length was subject to the National Speed Limit, though it also had driveways leading on to it and several sets of traffic lights. North of there, through to the end of the bypass at Robin Hood Gate, it was still just the old 1920s road, now limited to 40mph.

The Ministry demanded a fix, and Surrey County Council, acting as their agents, produced one. Front gardens were requisitioned and footpaths were pushed back, creating space for a dual three-lane speedway with flyovers and underpasses, flanked by service roads for the houses.

The scheme sounds monstrous, but it was built, and it gave us the Kingston Bypass we know today. The Hook Underpass came first, opening in 1960, and was quite a novelty: a model of it was donated to the Science Museum. But it only carried two lanes each way, and more were clearly needed. All the subsequent work to widen the Kingston Bypass, which continued through to the late 1970s, created three continuous lanes each way.

Hook is now a well known bottleneck as a result, not least because, in 1976, the Esher Bypass was bolted on to it. Initial plans had been for a bypass west of Esher, which would meet the southern end of the Kingston Bypass head-on, but eventually an eastern route was chosen, branching off the existing road just west of Hook.

This had the unfortunate result of directing three lanes of high speed traffic into the two lanes of the Hook Underpass, a problem that remains today. It also relied on the "County Link", a road that was supposed to be built by Surrey County Council from the Esher Bypass to the Scilly Isles Roundabout, approaching Kingston from the south. The creation of Greater London in 1965 removed all incentive for Surrey to build it, since it would now serve a London Borough and not Surrey's county town. It remains unbuilt.

The common touch

From Central London to Putney Heath, the A3 was the responsibility of the London County Council (LCC), and later the Greater London Council. The LCC's plans, in the early 1960s, were highly unusual.

Putney Heath, a large wooded open space between Putney and Wimbledon, was carved up by any number of roads that converged on the A3 towards Kingston in the west. The LCC's plan was to concentrate all that traffic on the A3, which would be widened, and as compensation for the land this occupied, most of the other roads would be torn up and returned to nature.

To make it work, the small and congested six-way roundabout at Tibbet's Corner needed an upgrade. The LCC designed a grade-separated junction, which was very generous: their Chief Engineer calculated the roundabout to have capacity twice the predicted demand, and the underpass even more. This lavish design was chosen to match the MOT's Hook Underpass further south, meaning a two lane underpass with a three-lane dual carriageway either side.

Keeping traffic flowing in all directions across the Heath was no small task. A temporary road was built south west of Tibbet's Corner to carry the A3 past the worksite, and returned to nature afterwards. Today you would never know that a road had ever run there, unless you knew that the space clear of trees matches its path exactly. The improved road and underpass opened in 1968.

To the south west, the improvement tied in to an earlier improvement project, where a three-lane dual carriageway had been provided on the A3 Kingston Road, and a new high-capacity signalised junction built where it met the A308 Roehampton Lane. It had been designed slightly too early, in an era when underpasses and flyovers were not yet planned for the whole of the urban A3.

To the north east, the Tibbet's Corner project ended on West Hill, the road lined with Victorian houses that carried the A3 into Wandsworth. The new three-lane dual carriageway narrowed suddenly into the suburban road, a temporary tie-in awaiting further improvements towards London.

The final stretch

By the start of the Greater London Development Plan Inquiry in 1970, the A3 had improvement works in hand or already complete for almost all its length in London. Just three gaps remained in the near-motorway route from rural Surrey to Ringway 2.

The first and most obvious was the connection from Tibbet's Corner to Wandsworth, which couldn't be built until Ringway 2 itself arrived. Designs for Wandsworth Interchange, where the expressway would finish, were provided to Wandsworth Borough Council in 1967, so it follows that there must have been a plan to get the A3 from Putney Heath to that point.

Unfortunately the drawings have not survived, so the route of the missing link remains a mystery. The two most likely options are on-line widening of West Hill, with a new route cut through the houses north of the A205 Upper Richmond Road to reach Ringway 2; or a route following the railway to East Putney. But no evidence exists to suggest what might have been planned.

The second gap is at Roehampton Lane, where the traffic lights were brand new. It's unlikely they would have been overwhelmed or needed replacement for a long time. But in a world where the rest of the A3 was a non-stop highway, there would have been pressure to remove this last set of lights. No such plans appear to have been drawn up.

The third and final gap is at Robin Hood Gate, the junction at the northern end of the Kingston Bypass, which today forms a nasty bottleneck, and the length of road from there to the county boundary where the LCC's dual carriageway began.

The Ministry's proposal, in the late 1960s, was for a large roundabout with a curved six-lane flyover carrying the A3. A continuous three-lane dual carriageway would run from the Kingston Bypass onto Kingston Road, with many of the houses on the south east side of the junction cleared away.

Detailed designs were drawn up and boreholes were drilled in 1971 to investigate site conditions, but work never began. Eventually a smaller scheme was carried out in the early 1990s, providing two lanes through the lights and an underpass for a new supermarket at Roehampton Vale.

It was the last improvement work the urban A3 was to see, and to a much smaller scale than the projects that went before - perhaps because, now, the expressway was never going to get beyond West Hill.

Sources

- A3 as Primary Road to end on R2 at Wandsworth; route Esher-Wandsworth to follow line of existing A3: GLC/TD/C/P/02

- Route, Esher Bypass, including County Link; initial plan to pass west of Esher: MT 120/273

- Junction layout proposed at Robin Hood Gate: GLC/TD/PM/CDO/07-068

- Kingston Bypass first proposed 1911: HLG 46/74

- Kingston Bypass opened by PM in 1927: MT 39/20

- Kingston Bypass construction standard: MT 57/83

- Surrey County Council designed A3 upgrades: GLC/TD/PM/CDO/07-069

- Hook Underpass model donated to Science Museum: Model of the Ace of Spaces Underpass, London; Science Museum Group Collection

- LCC scheme for Putney Heath and Tibbet's Corner: GLC/TD/C/36/013; GLC/TD/C/21

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Artist's impression of Tibbet's Corner and plan of Putney Heath scheme are extracted from GLC/TD/C/36/013.

- Photographs of concrete pouring in Tibbet's Corner Underpass, the Underpass shortly after opening and the traffic lights at Roehampton Lane are extracted from GLC/TD/C/21/003.

- Photograph of Esher Bypass taken from an original by Hugh Venables and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Kingston Bypass in 1928 is courtesy Britain From Above, EPW020677. © Historic England. Used under the "blogging use" licence terms.

- Photograph of buildings on Kingston Bypass in 1965 is extracted from item 6706/2/1 at Surrey History Centre.

- Photograph of A3 from Coombe Lane is taken from an original by Bill Boaden and used under this Creative Commons licence.