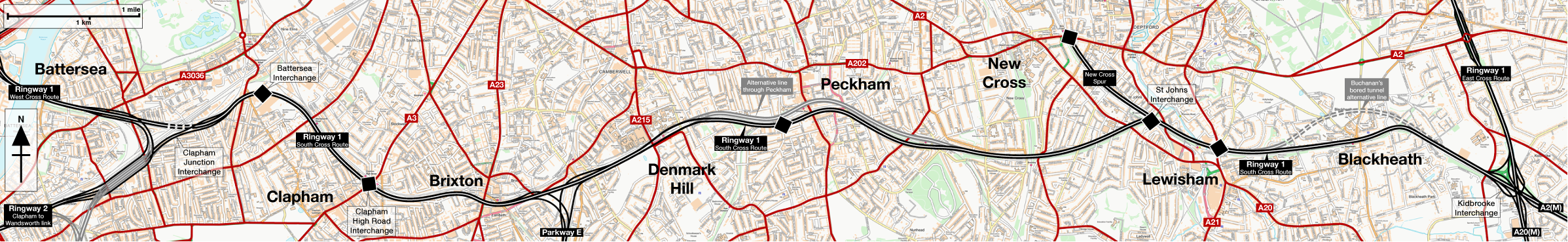

The South Cross Route was the most controversial and the most destructive component of Ringway 1, but also the one for which the least information is available.

For a long time it was assumed that this was because it had never been planned in any great detail, but that isn't the case. A firm of consultant engineers called Husband & Co. were commissioned by the London County Council to plan the route in detail, and by 1964 proposals had been drawn up for a motorway from Barnes to the Dover Radial Route at St Johns. In later revisions of the plan, as the Greater London Council took charge and began expanding the proposed network, the western sections of the South Cross Route were turned into parts of other motorways, and by the time the Greater London Development Plan went to public inquiry, the term "South Cross Route" was being used as we use it here, to describe the southern side of Ringway 1, from Clapham to Kidbrooke.

Only some of those plans have come to light so far, and because the route described by the name "South Cross Route" kept changing, and the roads connecting to it would shift location or vanish completely, they are only so much use in telling us what the South Cross Route was supposed to look like in the end. Nonetheless, there's enough information to accurately follow the alignment of the motorway and locate all its junctions.

Outline itinerary

Continues from East Cross Route

A2(M) and A20(M) (Kidbrooke Interchange)

Possible tunnel at Blackheath (cut-and-cover)

New Cross Spur to A2

Local connection to Peckham

Parkway E

A24 Clapham High Street

A3216 Queenstown Road

Clapham-Wandsworth Link

Continues to West Cross Route

Cost summary

| Property acquisition (1970) | £49,000,000 |

| Rehousing (1970) | £16,000,000 |

| Construction (1970) | £130,550,000 |

| Environmental works (1970) | £4,725,000 |

| Total cost at 1970 prices | £200,275,000 |

| Estimated equivalent at 2014 prices Based on RPI and property price inflation |

£2,770,209,368 |

See the full costs of all Ringways schemes on the Cost Estimates page.

Route description

This description begins at the eastern end of the route and travels west.

Kidbrooke to Denmark Hill

At the south-east corner of Ringway 1, the ring road would not have been the through route. Traffic coming off the southern end of the East Cross Route would have found the A20(M) straight ahead, and traffic going the other way, eastbound on the South Cross Route, would have flowed directly into the A2(M). Staying on Ringway 1 would have involved taking an exit sliproad in both directions.

Westward from there, the motorway would quickly join the north side of the railway line towards London Bridge, passing through Blackheath. Alongside the railway tunnel, the motorway was planned to run in a cut-and-cover tunnel of its own. To the west, Hurren Close in Blackheath might be recent development on a strip of land reserved for the motorway. An interchange serving Lewisham town centre would be located at St Johns, on the north side of the commercial area.

A little west of St John's, a three-way free flowing interchange would provide access to the New Cross Spur, which would continue along the railway towards London Bridge, terminating on the A2 at New Cross. (An original draft plan for the interchange, drawn in colour pencil, is shown right; click to enlarge.) This short spur would complete the bypass of the A2 through Greenwich, Kidbrooke and Eltham, and traffic continuing in towards London would return to the original road here. The South Cross Route itself would follow the other branch of the railway, joining the north side of the South London Railway. It would take out most of Geoffrey Road and the south side of Drakefell Road, among others.

Peckham was the first of the locations where a major town centre redevelopment plan was being drawn up, which would have seen the whole area cleared and reconstructed in 1960s style with high-rise towers and busy roads everywhere. The motorway was to take full advantage of this, ploughing through what is now Peckham town centre and interchanging with whatever new relief roads were being planned for the area.

The route then continues west, now on the south side of the railway, taking out most of Blenheim Grove. At Camberwell Grove, it would split, running with one carriageway on each side of the railway. Denmark Hill station would become a rather isolated and windswept place in the central reservation of a motorway. Some plans indicate that another local junction would be provided here to connect with the A215 towards Camberwell. In some very early draft plans, instead of a junction with local roads, there would have been a spur from the motorway running northwards to Camberwell Green.

Denmark Hill to Clapham

Both carriageways would come back together on the south side of the railway line before Loughborough Junction, where Parkway E would terminate at a free-flowing interchange. The railway line splits as it passes through Brixton, and the motorway was to run between the two tracks as it passed through the railway junction at Brixton. In Brixton town centre, where the South Cross Route bridged Brixton Road, it would have been at about sixth floor level. There would have been no junction at Brixton, but lay-bys for express buses were proposed here, as part of a public transport interchange between street-running buses, high-speed motorway buses, rail and the (then new) Victoria Line tube.

Brixton was, in fact, the next town centre redevelopment plan that the South Cross Route used to make its passage through South London easier. As part of the grand proposals, a restaurant was planned, suspended above the motorway, and the Victorian buildings of Brixton itself would be swept away, to be replaced with fourteen spindly tower blocks and a panorama of new concrete buildings. One of the original architect's models of this monstrous scheme survives, complete with endless towers and the suspended restaurant.

Moving back to the south side of the railway, the motorway's next interchange would be at the A24 Clapham High Street, another local junction which, despite its remoteness, would probably be the main access for Brixton. The route turns slightly northward here to reach the railway complex at Clapham Junction, and a final local interchange was proposed at the A3216 Queenstown Road before the route began dropping down below ground level. This would allow the motorway to curve under the main line tracks to Waterloo and Victoria, joining the north side of the West London Line railway. A major free-flowing interchange would have been built here, following the curves of the existing railway tracks, to provide access to the Clapham-Wandsworth Link.

Now heading north-west from Clapham Junction, the motorway would cross the Thames parallel to the railway and become the West Cross Route.

The battle for Blackheath

Today, the South Cross Route plans look appalling, blasting a path through several of South London's town centres and displacing more than 30,000 people. If it had been built, the motorway would also have been surprisingly inaccessible: only four or five local access points were planned, none with any adequate connection to the commercial heart of the area, Brixton. For the motorway to stand any chance of construction, enormously destructive redevelopment schemes would have had to go ahead in Lewisham, Peckham and Brixton, sweeping aside whole streets and shopping districts to make way for tower blocks, multi-storey car parks and concrete shopping centres.

Surprisingly, the most controversial issue at the time was nothing to do with this — it was actually about Blackheath, the "village" at the eastern end of the road near Kidbrooke Interchange. Residents there were worried that the characterful, historic feel of the suburb would be ruined by the motorway. Lewisham Borough Council agreed, and pleaded with the GLC for special consideration.

The initial proposal for the motorway would have seen it placed in cut-and-cover tunnel through the whole of Blackheath, so the finished road would have been buried underground and its impact on the village would have been minimal, but to build it, everything on the line of the motorway would first have to be demolished. That would have meant pulling down parades of Victorian shops on its main shopping street and a considerable number of handsome houses and villas. Whatever was built on top to replace those buildings would be unlikely to recapture the character of the area.

In 1967, very shortly after Ringway 1 was first unveiled to the public, the Blackheath Motorway Action Group was formed to oppose the plans, and its members put forward a proposal to re-route the section through Blackheath Village north of the town centre in a bored tunnel. The motorway would miss the centre of the village, and construction would require no demolition on the surface — but the cost would be dramatically higher. Their concerns were taken seriously and the GLC commissioned an official investigation. Studies were carried out, boreholes were drilled and civil engineer Colin Buchanan himself was commissioned to write a report examining the problem.

Four long years later, in April 1971, Buchanan completed his report, and to the relief of residents and campaigners he firmly recommended that the bored tunnel on his new line should be adopted as the final scheme. But the GLC remained silent on the matter: the Greater London Development Plan Inquiry was getting under way and there was silence from all quarters on the motorway plans.

The local press continued to worry that the new plan might not be adopted:

"Although the GLC never formally agreed to this alternative, they showed distinct signs of sympathy and carried out trial borings on Blackheath, presumably to determine the feasibility of a deep tunnel big enough to accommodate an eight-lane road.

"These borings were done three years ago [1968] and despite continuous pressure by the Motorway Group the GLC has never made public the results of the borings."

A tunnel to carry an eight-lane motorway would, of course, be a huge undertaking. The consultants for the North Cross Route recommended that, should a bored tunnel under Belsize Park be preferred to a cut-and-cover one, then four two-lane tunnels should be dug rather than two four-lane ones. Tunnelling technology at the time meant that anything larger would be more complex and too expensive. The same was proposed at Blackheath.

Rather unsatisfyingly, the story tails off there. Buchanan's report did not end the speculation or the debate, and within the GLC there continued to be indecision about the best way forward and uncertainty about the future of their motorway plans. And then, two short years later, the political landscape changed.

No decision was reached before the motorway proposals were deleted in 1973, and no tunnel ever troubled pretty Blackheath.

Changing priorities

The South Cross Route looks almost laughably unbuildable today, and indeed in the 1960s its route was no less urban or populous. Space was going to be made for it by piggybacking on a series of town centre regeneration plans - something that was then all the rage - across a swathe of inner South London. Brixton, Peckham and Lewisham were all set to be levelled and replaced with a new world of gleaming concrete, and space would be left in them all for the new eight lane motorway. Between them, houses would be cleared alongside railway lines to form a route.

Given the unbelievable scale of destruction and urban reconstruction this would have entailed, with hundreds if not thousands of fine Victorian buildings torn down and whole streets of homes, shops, schools and churches cleared away, it's remarkable that in a few places the South Cross Route's planners were very skittish about demolition.

At Peckham, the motorway was meant to cross to the south side of the railway as it approached the town centre from the east, then continue to the south, obliterating Blenheim Grove, before continuing west towards Denmark Hill. That would have required a crossing under the railway east of Peckham at a very oblique angle, and so in November 1970 an alternative was drafted to avoid the tricky bridgework by running the motorway along the north side of the railway through Peckham instead.

By February 1971, though, the northern routing was causing problems because six buildings on Holly Grove that would be cleared to make way for it were about to be given listed status, as were another eight on nearby Elm Grove. But returning to the original, southern line was also a problem, because numbers 9 and 11 Blenheim Grove were considered to be of "architectural merit" by English Heritage who had been glad to learn that they would be saved and would be quite unhappy if they were going to be condemned for a second time.

This state of uncertainty - just like in Blackheath - prevailed through to the motorway's cancellation in 1973.

Just before it was deleted from official plans, though, the GLDP Inquiry finished and the resulting Layfield Report made its pronouncement on the South Cross Route. Not only was it to be retained, Layfield suggested it should be brought forward and completed within the next ten years - by 1983. The GLC's plans had envisaged it coming late in the programme, probably to reach construction in the mid-1990s, because it was dependent on so many other regeneration plans - so how Layfield thought he could get it done sooner (and what he thought might be done about those lovely houses in Peckham) is something of a mystery.

Building the future

Not a single inch of the South Cross Route was ever built. But it still manages to cast a shadow over one small part of the communities it would have blighted. To see the extinct motorway's lasting legacy, you need only pay a visit to Coldharbour Lane in Brixton, where a building designed to reduce the impact of the noise and fumes it would create is still standing.

It's called the Barrier Block, an inviting nickname for a housing development if ever there was one (its official name is Southwyck House, though it rarely gets called that), and is known as a local eyesore. Its purpose was to save the Somerleyton Estate, which stands south of the building, from the noise and disruption of the motorway. It is very long and taller than you might expect, and its north-facing wall has only occasional, tiny windows because it was expected to face the motorway.

It is, literally, a barrier that people were expected to live in, running alongside the proposed motorway. It leans outward, each floor overhanging the last, in a design that was supposed to deflect noise from the motorway downwards. Unlike the rest of Lambeth's vast, concrete-heavy plans for Brixton, this is one part of the 1960s vision of the future that actually transferred to the real world.

Sources

- Route: Kidbrooke - Denmark Hill from T 319/1842; Denmark Hill - Battersea (including some interchanges) GLC/TD/DP/LDS/02/097.

- Layout of Kidbrooke Interchange: HLG 159/1257.

- Blackheath tunnel and alternative line proposals: HLG 159/1257 and ACC/3499/EH/08/04/019 for proposals made by LB Greenwich and Buchanan; MT 106/299 for report in South London Press, including trial bore holes made by GLC.

- Amendments to line at Peckham: ACC/3499/EH/08/04/019.

- Early proposal for spur to Camberwell: MT 106/195.

- Layfield Report proposes re-phasing to complete by 1990: HLG 159/626.

- Brixton section, and redevelopment of Brixton: LBL/BDD/1/16/1, LBL/BDD/1/16/2 and LBL/BDD/2/4.

- Barrier Block/Southwyck House: Urban 75 have a well-researched report from original files at Lambeth Archives, verified by the site's authors.

- Commissioning engineering reports and funding: MT 106/299.

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Artist's impression of motorway through Brixton from "Brixton Town Centre", London Borough of Lambeth (LBL/BDD/1/16/1).

- Plans of tunnel alignment at Blackheath and alternative motorway line at Peckham Rye are from ACC/3499/EH/08/04/019.

- Photograph of Blenheim Grove taken from an original by Marathon and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Image of Southwyck House taken from an original by Stephen Craven and used under this Creative Commons licence.