The Greater London Council's policy for the shape of London went to public inquiry in 1970, and its monolithic motorway plans came under detailed scrutiny for the first time. The Greater London Development Plan Inquiry was to become the longest planning inquiry in British history - and marked the start of the end for urban motorways in the capital.

The inquiry had been fully expected for some years. GLC publicity from the mid-1960s had reassured Londoners that it meant anybody could raise an objection and that "nothing can just slip through". It was convened in July 1970 under Frank Layfield QC, a leading expert on planning law.

Among the objections to high-rise buildings, open space policy and waste disposal, one subject took up more time than any other, accounting for more heated debate, disagreement and animosity than anything else. 30,000 objections to the GLDP were received, and three quarters of them related to the GLC's motorway plans. Everyone, it seemed, had something to say about the Ringways.

Hearing the evidence

The Westway and West Cross Route opened to traffic in the very month the inquiry started, and as the first hearings took place, newspapers carried pictures of houses alongside the new motorway draped with homemade banners reading "get us out of this hell".

But despite the horror felt nationwide, the GLC wanted to press on, insisting the seriousness of London's traffic problem made the next phase of the Primary Road Network inevitable. The West Cross Route from Holland Park to Chelsea had already been through the legal process, and planning was well advanced on Ringway 2 across the Thames in East London. Both were due to start construction in 1972 - but Whitehall intervened, and there was bitter disappointment at County Hall that work couldn't proceed until the inquiry had concluded. If the GLC had its way, both those roads would have opened around 1975.

The GLC presented the inquiry with its draft Greater London Development Plan and a mountain of supporting evidence to explain and justify its decisions. And then the hearings began. Over 22 months, the panel saw 326 witnesses, all carefully selected to represent the breadth of views of the thousands of objectors. Among the representatives of London boroughs and business interests were many ordinary citizens.

Planning historian Douglas Hart has estimated that, by July 1970, there were more than 100 dedicated pressure groups across London fighting the motorway plans. Many attended the inquiry. Most had been in correspondence with the GLC for some time, but the Council's unwillingness to discuss details meant that the atmosphere was often acrimonious. Making enemies of the people whose support was needed the most was an incredible failing: this was an era when the traffic problem was a source of widespread anxiety. Most of the anti-roads groups actually agreed that something had to be done about the traffic; they simply disagreed with the GLC's solution.

Fear and resentment continued to grow, and in 1971 many small groups across London formed a coalition called the London Motorway Action Group. Together with LATA and Stop the Box, they were rarely out of the press and seemed to represent the mood of the people. Typical of the determination and eloquence of the protestors at the inquiry were the Chiswick House Area Residents' Association. They became self-taught experts in the emerging science of sound profiling, bringing plans and charts to demonstrate how a triangle of three motorways would eradicate a large part of Chiswick and render 68% of what remained uninhabitable due to noise and fumes.

For the boroughs, meanwhile, Hackney produced its own traffic forecasts showing that the North Cross Route would actually make traffic worse across most of its borough, not better. Lambeth wanted planning controls lifted along the route of Parkway E, which was sterilising swathes of land through Tulse Hill and West Norwood for the benefit of a route only pencilled in for construction in the next century. And Bromley's alternative line for Ringway 2 through Beckenham was so much less destructive than the original that the inquiry panel must have wondered whether the GLC had thought through their ideas at all.

One voice notably absent from the inquiry was the Ministry of Transport. The MOT had helped set up the London Traffic Survey, guided the GLC's policy on transportation and would build about half the urban motorway network. It was the supporter of the Ringways in Government, but three months in to the inquiry it ceased to exist.

In October 1970, three Ministries - Housing and Local Government, Public Building and Transport - were merged into a new "superministry", the Department of the Environment. The MOT was supposed to make the case for its plans to Layfield's panel, and the Minister of Housing and Local Government was supposed to decide what to do when the inquiry concluded. Now, though, they were one and the same. The DoE could not be an advocate at its own inquiry, and its roads branch agreed only to answer factual questions, refusing to make the case for the motorway network it had encouraged the GLC to plan.

Indeed, aside from the GLC, there was literally just one group that spoke in favour of the Primary Road Network. In 1971, the British Road Federation made a public announcement calling the GLDP "magnificent". In that, they were alone.

An unhappy verdict

Layfield and his colleagues grew increasingly frustrated with the Greater London Council. In early 1972, tired of fluff and bluster, they made a very specific demand for detailed costings for the whole road network (which you can see in full on the Cost estimates page) in an attempt to get some hard facts on which to base their recommendations.

The GLC, for their part, actually revised the GLDP during the inquiry in response to the criticisms it was facing. A new emphasis was placed on public transport and traffic restraint - but the motorways remained. When the inquiry concluded, and the resulting report was published, the panel's frustration was evident.

Layfield said the GLDP was overambitious and inconsistent. Evidence had been gathered by the GLC to justify its vision, but the Plan, he said, failed to relate that information to policies, failed to relate policies to aims, and failed to present its aims in meaningful terms. It was little short of a complete demolition of the GLC's masterwork. And the motorways, like much else, failed to add up.

...the motorways might generate an unacceptable amount of traffic in Central London unless strict management and stringent restraint were applied. There was no evidence in the Plan that such ameliorating policies were intended. But, if such controls were introduced in parallel with motorway construction, then the provision of orbital capacity was too lavish and would be underutilised

In terms of affordability, Ringway 1 gave the best return on investment, but even that was "inadequate by usual standards". Not that Layfield even thought the GLC's motorways were necessarily the answer.

...the GLC, when faced with a variety of solutions to a problem, chose one on political grounds and then presented it as inevitable

So what was to be done? Layfield recommended scrapping about half the Primary Road Network. Ringway 2's controversial Southern Section was out, though a stub would remain across the Thames in East London to serve Thamesmead. He saw no need to bulldoze Ringway 3 through south and west London when the South Orbital Road was already in hand, instead suggesting new links to join the north and east sides of Ringway 3 to the South Orbital. In doing so, he created the route of the M25 as it exists today.

Astonishingly, though, Layfield retained Ringway 1 in modified form, renaming it the Inner London Motorway, and re-aligning the East Cross Route across the Isle of Dogs to St Johns to make the circuit smaller and closer to central London. Finally, he said the whole network should be complete within 20 years - by 1992 - in order to minimise uncertainty and planning blight.

When the report was released, it caused a storm in the press, especially when the new Environment Minister, Geoffrey Rippon, seemed to have signalled his approval of the report. His press office quickly clarified that he had not commented either way. The Sunday Times ran a two-page spread on 11 February 1973, despairing under the headline "The Motor Car Wins its Biggest Victory", and others ran stories describing the shock that Layfield had recommended building Ringway 1 in all but name. Many argued against the plans in their editorial pages.

Stand by for fireworks

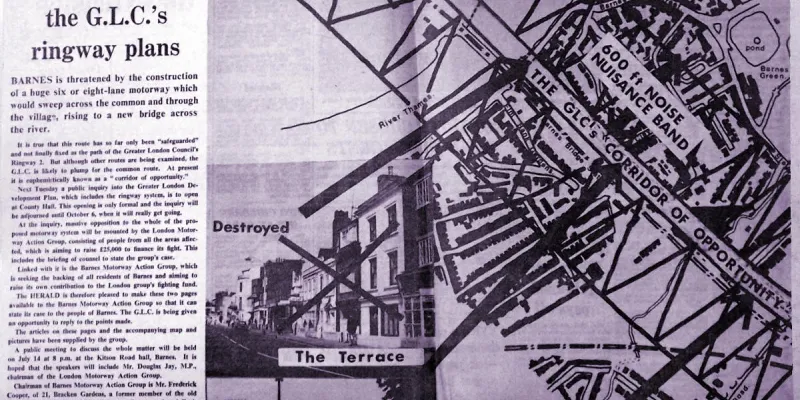

Outside the inquiry, the world had been steadily changing. Protest groups across London had been pressing London's councillors and MPs. Local newspapers gave voice to public fear and outrage on behalf of their readers, and some went to unusual lengths in support of campaigners. In the same month the inquiry started, for example, the Putney and Roehampton Herald gave the Barnes Motorway Action Group a double-page spread for free to explain their cause.

By early 1972, the barely lukewarm support of the boroughs had cooled even further. Under the headline "Councils combine to fight M-way 'madness'", the Clapham Observer reported the remarkable development of five boroughs joining forces to openly wage war on the Greater London Council.

Five South London Councils - Lambeth, Lewisham, Merton, Southwark and Wandsworth - have agreed to combine to fight proposals to drive motorways through their boroughs...

Coun Geoffrey Manning (Lambeth) who presided at the meeting, said: 'We agreed to examine all legal means of whipping up public support against this intolerable imposition on the urban environment... We are now getting down to planning a co-ordinated fight against this monstrous motorway madness on a regional basis. Stand by for fireworks.'

The happy political consensus of the 1960s was rapidly disintegrating. Doubts among the Labour members of the GLC had been growing for several years as public opposition grew, and in June 1972 Sir Reg Goodwin, leader of the GLC's Labour opposition, dramatically withdrew his party's support for Ringway 1 and Ringway 2.

Labour pledges itself to abandon the disastrous plans to build two motorways which threaten the environment of Central London

The GLC's Conservatives, then in control of the Council, held out for a further three months before beginning a cautious retreat, quietly suggesting that a single urban motorway ring could be built via the North Circular Road, avoiding some of the most controversial parts of the Primary Road Network.

By the time Layfield's report was published in December 1972, it was halfway to irrelevance, a detailed critique of a plan the GLC's leadership and opposition had both abandoned. But such things make no difference to statutory planning procedures. The finished report was formally delivered to the Department of the Environment, and in February 1973 the Government warily decided that "an endorsement of the need for an inner Ringway, without committal to the line" was now official policy.

In mid-February 1973, amid the backlash in the press, the Cabinet's Ministerial Committee on Regional Policy and the Environment met to discuss the Layfield Report. Despite the cost and controversy, Geoffrey Rippon's approval of the report appeared to sway opinion at the top tier of Government, and Ringway 1 was given the green light.

This surprising decision didn't stay within the walls of Downing Street for long. The details were leaked to Private Eye, which printed a story on 23 February quoting Rippon's suggestion that the committee approve Ringway 1 and kill off the southern part of Ringway 2 to "bring some certainty into the prolonged and frustrating debate about motorways in London". There was panic within the Treasury, and an internal investigation was launched to trace the source of the leak. In actual fact, it hardly mattered.

Out on the streets of London, campaigning was getting under way for April's local elections. Council elections are often swayed by the popularity of the Government, and Ted Heath's Conservative administration was not faring well in the polls. His party would have to fight to retain control of the GLC. But the single biggest political issue in London was the GLC's motorway network, and on that topic one party captured the public mood. The Tories hoped their watered-down Ringway network would appease both frustrated drivers and worried residents. Labour, on the other hand, campaigned hard on a manifesto that would see the motorways scrapped, public transport funding vastly increased and traffic restraint to rein in congestion.

On 12 April 1973, London went to the polls, and decisively handed victory to the Labour party. The Conservatives lost just over half their seats on the Council, and the key factor is usually considered to have been their pledge to scrap the Ringways.

The priorities of the new Labour GLC were clear. On Friday 13 April, Sir Reg Goodwin returned to County Hall as the new leader of the Council. His first act, having removed his hat and coat, was to direct the Planning and Transportation Department to abandon all plans for the two innermost motorway rings. Without them, the future of the remaining motorway schemes looked decidedly uncertain. The Ringways were dead.

Epilogue

1973 was the year the Ringways were killed off and it was also the year that work started on a new motorway between Potters Bar and Cheshunt, known as M16, that was designed to form the first part of Ringway 3. By the following year, planners at the DoE were discussing a new concept called LOOR, short for the "London Outer Orbital Road", a project that would join the M16 and the South Orbital Road to make one motorway circuit of London. Eventually a single number was chosen for it: M25.

The fallout from the GLC elections caused further changes to the Greater London Development Plan, and when it was finally published in 1976 it contained almost no new road proposals. The east side of Ringway 2 was retained to promote redevelopment, and there were vague promises to look at improving traffic movement along broad corridors that loosely resembled some of the abandoned motorways.

For its part, the GLC briefly flirted with alternative ways to provide new roads, commissioning a report called Roads in Tunnel, published in December 1973. It investigated ways to build long lengths of motorway-like roads underground, recommending cut-and-cover junctions linked by bored tubes as the best method, and set out proposed standards and likely costs. By the time it was published, though, it was clear the GLC was not going to be spending that sort of money on new roads, no matter how well hidden.

In 1986, Margaret Thatcher's Conservative Government had two of its most memorable achievements: completing the M25, and then abolishing the GLC.

The final sections of M25, opened that year, were junctions 3 to 5 and junctions 19 to 23, the two links that joined the north and east sides of Ringway 3 with the south and west of Ringway 4. The new sections closed the coffin on the Ringways by botching together the most easily built bits and pieces to form one lumpy circuit. This is the M25 we see today: two halves of two different ring roads.

Within London, traffic continued to grow and congestion had worsened since 1973, but for obvious reasons, no GLC administration had the political will to tackle it. The Government saw the GLC's removal as an opportunity to intervene on behalf of the motorist, and began a programme of improvements to the North Circular Road and the A40. Ringway-era proposals were dusted off and some made it to construction, not least the A12 between Hackney Wick and Redbridge, a 1990s reimagining of the cancelled southern part of the M11.

Four "London Assessment Studies" were also commissioned in 1986, examining ways to improve traffic flow in particular areas of the capital. Out of these came the Western Environmental Improvement Route, a resurrected Ringway 1 West Cross Route; comprehensive improvement plans for the South Circular Road involving tunnels under Clapham Common and Forest Hill; and an ambitious idea to tunnel lengthways underneath the Thames all the way from Chiswick to Wandsworth.

Transport minister Cecil Parkinson was in office when these ideas were put to the public, and the response was little different to the message the GLC had received in the early 1970s. Londoners may complain about the traffic, but they will rarely agree to new roads carving through their suburbs. In April 1990, with local elections just a month away and highway plans facing huge opposition, Parkinson dropped all of the new road proposals, hoping to see off another 1973-style defeat across the 32 London boroughs. In their place he announced new funding for public transport and the creation of "red routes" to control parking on London's busiest streets.

The final indignity to London's few surviving urban motorways came in 2000, when responsibility for London's main roads passed to a new body called Transport for London. TfL doesn't have the authority to operate motorways, so the remnants of Ringway 1 were downgraded. The A40(M) Westway became plain A40, the A102(M) East Cross Route is now A12, and the grandiose M41 West Cross Route was demoted to the utterly forgettable A3220, completing a journey from notoriety to obscurity in the space of thirty years.

TfL has built just one new road since its inception: the A23 Coulsdon Relief Road, a single-carriageway less than a mile in length with a 30mph speed limit and several sets of traffic lights.

London is not a city in which new roads are built, and most people have long since forgotten that it ever might have been.

Sources

- GLDP as longest planning inquiry: Read, Lionel. (2000) "Sir Frank Layfield: Obituary", The Guardian.

- GLC reassures that "nothing can just slip through": "This Way to London: A Summary of the Greater London Development Plan", (1969). London: Greater London Council.

- Number of objections, days panel sat and number of witnesses; GLC revise GLDP during inquiry; creation of DoE and effect on inquiry; BRF as only group in favour; number of pressure groups at 1970; changes in party policy during 1972; Labour cancelling Ringways on first day in office: Hart, Douglas (1976). "Strategic Planning in London: The Rise and Fall of the Primary Road Network". London: Pergamon.

- GLC desire to build WCR and R2 East despite inquiry; construction scheduled for 1972: WCR HLG 159/1024; R2 GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/084.

- Chiswick House Area Residents' Association evidence to inquiry: HLG 159/2342.

- Borough objections to GLDP: Hackney and traffic forecasting HLG 159/2541; Lambeth and Parkway E HLG 159/1373; Bromley alternative line HLG 159/2183.

- Layfield panel demand detailed costings: HLG 159/2673.

- Layfield Report and recommendations: HLG 159/626.

- Barnes Motorway Action Group newspaper spread: "What the Motorway Would Do to Barnes", Putney and Roehampton Herald, 2 July 1970.

- Coalition of South London councils: "Councils combine to fight M-way 'madness'", Clapham Observer, 11 February 1972.

- Press response to Layfield; Rippon's approval and press office insistence he had not commented; memo recommending Layfield proposals; policy on Ringway 1; leak in Private Eye: T 319/2655.

- GLC election results 1973: Greater London Council Election Results.

- "LOOR" and single orbital route: MT 120/315; M25 as name of full circuit: MT 120/316/1.

- GLDP published 1976, lack of road proposals: "Greater London Development Plan: Approved by the Secretary of State for the Environment on 9 July 1976". (1976). London: Greater London Council.

- GLC investigation of tunnelling roads: Sir William Halcrow and Partners & Mott, Hay and Anderson. (1974). "Roads in Tunnel". London: Greater London Council.

- Commissioning of London Assessment Studies: "Traffic in London: a Discussion Document on Initiatives to Tackle the Problems" (1989). London: Department of Transport.

- Cancellation of London road schemes in 1990; instatement of public transport measures and Red Routes: HC Deb (27 March 1990) vol. 170, col. 222.

- Motorways within Greater London downgraded: "Transport for London", SABRE Wiki.

Picture credits

- Photograph of protest at Acklam Road taken from The Underground Map and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Noise profile map of Chiswick extracted from HLG 159/2342.

- Model of Brent Cross is taken from "Tomorrow's London: a background to the Greater London Development Plan".

- Gerald Scarfe editorial cartoon is taken from the Sunday Times, 11 February 1973.

- Barnes Motorway Action Group message and map are taken from the Putney and Roehampton Gazette, 2 July 1970.

- Plan of reduced motorway network as proposed by GLC Conservatives is taken from The Croydon Advertiser, 8 September 1972.

- GLDP Roads Map taken from the published GLDP, as below.

- Photograph of North Circular at Stonebridge Park taken from an original by Stacey Harris and used under this Creative Commons licence.