Fuel rationing and depopulation in the years after the war provided a break from steadily increasing traffic and congestion. But by the late 1940s, the number of cars on the road and the resulting delays to journeys were creeping upwards. The traffic problem was once again on the agenda.

Abercrombie's County of London Plan and Greater London Plan, drawn up in 1943 and 1944, were already looking increasingly unrealistic. Their wholesale redevelopment and rezoning of London was abandoned in the rush to rebuild, so space for a new network of roads to ease the traffic problem did not exist. In the years that followed, the London County Council was forced repeatedly to redraw its road plans in response to the failure of the masterplan, a lack of Government support and a growing panic as forecasts for car ownership and traffic congestion spiralled ever upwards.

A change of plan

Without comprehensively restructuring London's districts into self-contained "precincts", as per Abercrombie's plan, space for new roads was not being created as the city was rebuilt. The LCC overcame this problem in the late 1940s by modifying Abercrombie's road network to align it with the existing street plan. Building those roads would still, however, involve widespread demolition to clear wider paths through the urban area.

Their biggest headache was the cost and disruption of Abercrombie's cross-city routes "X" and "Y". Building entirely new Arterial Roads north-south and east-west through Central London, meeting at a complex part-tunnelled interchange in Bloomsbury, was looking less feasible by the day as new buildings were erected and property prices climbed steeply.

The LCC developed a cunning scheme to avoid building them at all. In the original plan, the "B" Ring was an Arterial Road, the innermost ring road for fast through traffic, while the "A" Ring was Sub-Arterial, made up of wide streets with buildings alongside. By swapping the functions of the "A" and "B" Rings, the innermost circuit would have vastly increased capacity, removing the need for through-routes within it. So, in 1948, a detailed assessment was carried out, the "B" Ring was duly demoted to Sub-Arterial status, and the Arterial "A" Ring was born. A workable solution to the traffic problem seemed to have been found.

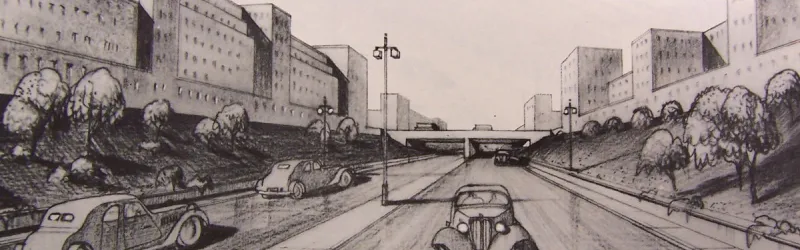

The Arterial "A" Ring was planned in some detail and the LCC were serious about building it. Running mostly inside the present Inner Ring Road, it would be either elevated or depressed below ground level as it passed through different areas. Through Hyde Park and across the Thames near Tower Bridge it would run in tunnel, and below certain particularly significant streets, buildings would be constructed across it to mask its presence.

The ring road would have had three lanes in each direction (except under the Thames, where the tunnel would only have two) and would form a non-stop uninterrupted circuit, with grade-separated roundabout interchanges at just nine points:

- Angel (for the A1)

- Aldgate (for the A11 and A13)

- Abbey Street (for the docks)

- Old Kent Road (for the A2)

- Kennington Park Road (for the A23)

- Vauxhall

- Eaton Square (near Victoria, with a spur to the A4)

- Montagu Square (near Marble Arch, for the A5, A40 and A41)

- Tottenham Court Road

It would be restricted to motor traffic only, with a minimum speed limit and no stopping allowed. In all but name, it was a 1940s motorway.

Feasible, affordable, suitable?

The LCC made the Arterial "A" Ring their top priority road scheme, and expected work to begin when housing availability returned to pre-war levels so the Council's housing programme could accommodate people displaced by the road. The first section would be the most needed, from Eaton Square to Angel. Redevelopment would follow, filling the space under its viaducts with shops and studios, and building long blocks of offices and flats along its embankments to hide it from surrounding streets.

In April 1950, the Council was drawing up its Development Plan, a statutory document to set out its town planning policy for the coming decade. They were keen to include the Arterial "A" Ring, but it could only go in if the route could be safeguarded, and at that time, safeguarding the line of a future road required the approval of a Parliamentary Committee.

The LCC submitted a detailed application to the Committee, gravely stating that if action were not taken, the line would quickly be lost and a similar road scheme may never again be possible. The Arterial "A" Ring, they said, was the only solution that was feasible, affordable and suitable for the needs of traffic, and that asking the Council or Ministry of Transport to reconsider was not an option, as neither had any alternative proposal to suggest.

At this point Hugh Dalton, Minister of Town and Country Planning, intervened. He declared the £88m price tag too high and, in May 1950, brought down the axe on the whole scheme. The Arterial "A" Ring was suddenly without a route and without funding. It continued to be talked about, and even appeared in occasional LCC documentation for the rest of the decade, but it would never be built.

London's key ring road was dead. What now?

The ghost of a plan

Perhaps the Arterial "A" Ring was never realistic. Its cost was only the start: land values in Central London were prohibitively high and escalating, and it came with the unwritten assumption that major radial routes would be extended right in to meet it. Until 1959, there continued to be occasional references to the M1 terminating at Marble Arch, a legacy of the Arterial "A" Ring's junction at nearby Montagu Square. That sort of thing was clearly not viable, but in its absence, the London County Council Development Plan of 1951 had no response to growing traffic congestion. It talked about managing traffic "on existing routes with additions and improvements where necessary", concentrating limited funds on a small number of junctions.

Abercrombie's ambition for five concentric rings and a strict hierarchy of roads was gone, but its ghost persisted in the Plan's accompanying maps. Around Central London, a ring of existing streets were marked along something like the "A" Ring's route, resembling the modern-day Inner Ring Road. Where the "B" Ring would have run, further streets were marked, not forming a complete circuit but clearly intended to perform the ring road's function, distributing traffic around the central area.

The specially marked roads were the LCC's target for investment, and to identify them, it gave them names. The erstwhile "A" Ring was now the "Inner Circuit Route", and others through and around it were called things like the "North West Cross Route" or the "East-West Cross Route". Between Shepherd's Bush and Chelsea, the "West Cross Route" would help traffic cross the river, while new approaches to the Blackwall Tunnel went by the name "East Cross Route". Some of these names would eventually be given to motorways, but not just yet.

Keeping the faith

Without the prospect of safeguarding, the London County Council's planners couldn't include the "A" Ring or any other major new road in their official policy, and for the rest of the 1950s their skeleton programme of minor junction improvements continued. Behind the scenes, however, there were no such restrictions. It was accepted wisdom within the Council, the Ministry and Government at large that the traffic problem was a catastrophe in the making; sooner or later, drastic action would have to be taken. And so, secretly, the LCC continued to think about new ring roads.

Nothing could realistically be built as close to Central London as the old "A" Ring. Instead, Abercrombie's two inner rings were scrapped, and the LCC's team of planners looked elsewhere to find a more accommodating route. A circuit was possible following railway tracks, further out than had previously been thought ideal and at varying distances from the centre, but land would be cheaper and following railways would be far less disruptive.

The new route was a trapezoidal motorway through Willesden, Highbury, Hackney, Blackheath, Brixton, Clapham and Shepherd's Bush. They called it the London Motorway Box.

Several iterations of the Box were drafted, with adjustments to the route, the location of junctions, connecting spurs and radial routes. Until about 1964, its eastern flank would have run from Dalston to New Cross via Wapping and Rotherhithe, a line that was abandoned when the existing Blackwall Tunnel and East Cross Route were incorporated into the circuit. Outside the LCC's boundaries, the Ministry of Transport began sketching plans for Abercrombie's "C" and "D" Rings, their specifications gradually upped to something like motorway standard.

London's epic road plan had just been born - and nobody knew anything about it.

Not an art but a science

By the late 1950s, it was becoming clear that the recovering economy would soon allow much greater investment in transport and infrastructure. That meant an opportunity to finally tackle the growing traffic problem.

Until now, road improvements and new roads had been planned on the basis of small-scale traffic surveys and the informed opinion of engineers, but the trend in the United States was for major studies to be carried out, providing an empirical basis for road investment. The same was now going to be tried in London.

Launched in 1960, the London Traffic Survey would have two phases. The first would assess demand for travel across the whole of the London region; the second would predict future demand and recommend roads to accommodate it. In Phase I, all transport facilities within the green belt were analysed and 50,000 households were surveyed - 2% of the total population of London. Phase II created detailed forecasts showing the demand for travel between each of 900 distinct areas of the city in 1981.

The LTS would later be used to justify the decision to build a network of motorways across London in a pattern of rings and radials. In truth, however, the decision to do that had already been taken by 1960, and no other form of road network was ever tested against the survey's findings.

Unwrapping the box

The Motorway Box and the other plans coalescing around it remained a secret even as firms of consulting engineers were brought in to help develop them. Husband & Co. had, for example, prepared an engineering report and detailed designs for the Westway and the first phase of the West Cross Route by the end of 1961. But still it was all under wraps.

The cat was let out of the bag in the most bizarre of circumstances. In 1964, Battersea Borough Council wanted to build a swimming pool as part of the new Winstanley Estate near Clapham Junction, but couldn't get planning permission.

The fact came out under persistent questioning that the then London County Council was sitting on plans for a vast network of motorway rings round London, a section of which would sweep through the site where the baths might be.

Government files from the same period suggest the dispute was not as dramatic as this article would suggest, but nonetheless a situation was reached where not just some swimming baths but also a brand new twelve storey tower block were on the line of a planned motorway, resulting in the exchange of a considerable amount of disgruntled correspondence.

The secrecy would have to come to an end because the plans were going to have to be published sooner or later, but that wouldn't be the London County Council's problem.

On 1 April 1965 the old LCC was abolished and replaced by the new Greater London Council, which would pick up the task of planning London's future road network - and it would do so with more enthusiasm and vigour than any organisation before or since.

Sources

- Proposal to reverse roles of "A" and "B" Rings, cancellation of Routes "X" and "Y": MT 95/86; London Road Plans 1900-1970 (1970), CM Buchanan, GLC Information Centre.

- Attempts to safeguard line of Arterial "A" Ring; route, engineering standard, proposed restrictions: MT 110/3.

- M1 to terminate near Marble Arch: MT 112/67.

- Road proposals in London County Council Development Plan 1951: GLC/TD/DP/DC/43/010; London Road Plans 1900-1970 (1970), CM Buchanan, GLC Information Centre.

- London Traffic Survey: Strategic Planning in London: The Rise and Fall of the Primary Road Network (1976), Douglas A. Hart, Pergamon Press; Movement in London: Transport Research Studies and their Context (1969) GLC.

- Motorway Box in planning despite not appearing in 1951 plan; early draft for eastern flank via Rotherhithe: MT 106/195.

- Westway and West Cross Route planning: West Cross Route: Interim Report on Stage I (1962).

- Planning dispute over Winstanley Estate: GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/027; extract from New Society: T 319/1842.

Picture credits

- Plan and artist's impressions of the Arterial "A" Ring extracted from MT 110/3.

- Photograph of Montagu Square taken from an original by David Edgar and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Draft plan of London Motorway Box circa 1963 from MT 106/195.

- Graph showing vehicle numbers extracted from Traffic in Towns (1963), HMSO.

- Photograph of the Winstanley Estate taken from an original by Derek Harper and used under this Creative Commons licence.