This page is about abandoned proposals to incorporate the M23 into an urban motorway network for London. Information about the motorway as it exists today is in the Motorway Database.

It might be the most obviously unfinished motorway in the whole UK, let alone in London. The M23 was supposed to link London with Crawley - but its urban section was a problem that couldn't be solved.

The earliest plans for a motorway heading south from London were made in 1906. It was the first such plan in UK history, a private toll motorway from London to Brighton. A similar idea returned in the late 1920s, before plans were made by various branches of Government in 1937, 1944 and 1959.

A definitive plan was produced in 1964 and a line was fixed for the whole motorway, beginning at Streatham and extending to the south of Crawley, but the same question vexed this plan as all the others - which of South London's inadequate roads could offer a terminus for the M23? The issue plagued planning for the motorway and no satisfactory answer could be found, until at last in 1969 the GLC unveiled their new suburban orbital motorway, Ringway 2. It finally meant that legal orders could be made and a public inquiry held. All that remained was to build it.

In the early 1970s, a contract was let to build the rural southern half of the M23, the part outside London. It was completed in 1976. The remaining urban section was only waiting for the conclusion of the Greater London Development Plan Inquiry. But the fallout from the Inquiry, and the other political changes happening in London, meant that it became impossible to build, and despite attempts to develop a new plan, the problem of the M23 could never be solved.

Today the motorway begins just outside London at junction 7, where empty bridges and stubs of road point north towards a city the M23 will never reach. The unbuilt length continues hold a strange fascination, though, and it's described here in detail.

Outline itinerary

Possible extension to Parkway E

R2 Southern Section (Streatham Vale or Delta Interchange)

A236 Croydon Road (Mitcham Common Interchange)

A232 Croydon Road (Beddington Interchange)

R3 Southern Section

A23 Brighton Road (Hooley Interchange)

R4 South Orbital Road (Merstham Interchange)

Continues to Gatwick Airport and Crawley

Cost summary

| Property acquisition (1970) | £17,400,000 |

| Rehousing (1970) | £2,900,000 |

| Construction (1970) | £50,075,000 |

| Environmental works (1970) | £1,995,000 |

| Total cost at 1970 prices | £72,370,000 |

| Estimated equivalent at 2014 prices Based on RPI and property price inflation |

£741,563,976 |

See the full costs of all Ringways schemes on the Cost Estimates page.

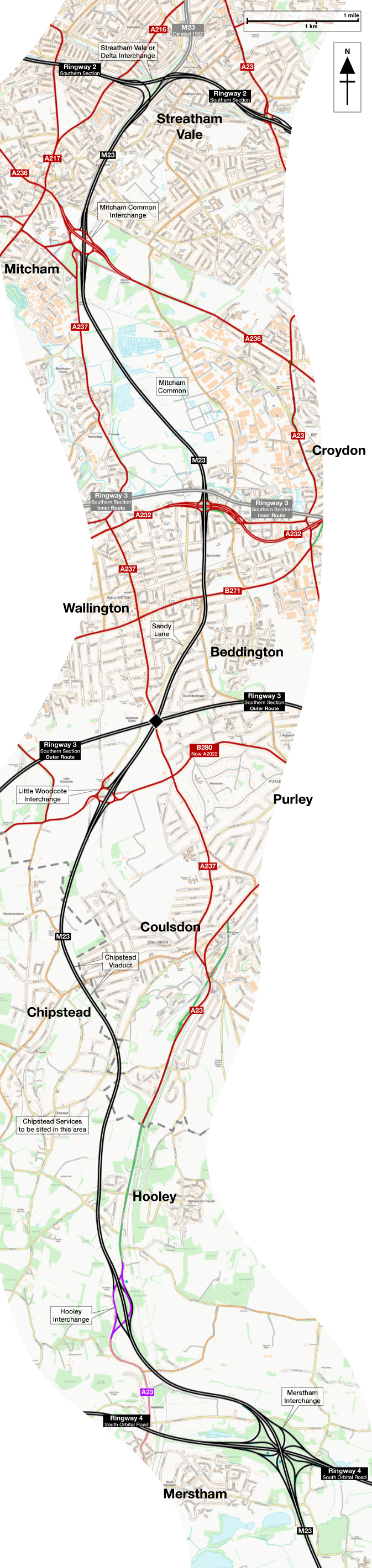

Route map

Scroll this map to see the whole route

Scroll this map vertically to see the whole route

Route description

This description begins at the northern end of the route and travels south.

Streatham to Merstham

The M23 would begin on Ringway 2's Southern Section at Streatham Vale, at a three-way free-flowing junction, known variously as Streatham Vale Interchange or Delta Interchange. Two-lane sliproads from each direction would come together to form a dual four-lane motorway.

Running along the east side of the railway towards Mitcham Junction, the motorway would pass through areas that were vacant or brownfield land in the 1960s, but have since been infilled with housing developments. Grove Road, and all the houses facing it, would be obliterated. Emerging into the open space of Mitcham Common, a vast three-level roundabout junction would be formed to connect with the A236 Croydon Road and A237 Carshalton Road.

The motorway would then curve south east to cross the common diagonally, skirting the water treatment works and passing through the grounds of Carew Manor to reach the A232 Croydon Road. Here another three-level roundabout interchange would provide access to an upgraded road towards Croydon, and if Ringway 3's Southern Section had been built on the inner route, it too would have crossed here.

The M23 would then enter a walled cutting. The woodland on Queen Elizabeth Walk, and the adjoining houses on Rookwood Avenue, would all be cleared to make space for the motorway to run in a deep trench.

Crossing Tharp Road and taking the corner of Mellows Park, the motorway would then join the east side of Sandy Lane, still in cutting, requiring the demolition of large detached houses. It would turn south west, staying parallel to Sandy Lane South, but now running through the long back gardens between the houses on the south side of the road. The large houses would remain, but would have short gardens overlooking the motorway.

If Ringway 3's Southern Section had been built on the outer route, it would meet the M23 near the A237 Woodcote Road. The motorway would continue into open countryside, and a roundabout interchange would be provided at the A2022 Woodmansterne Lane.

Curving south and then south east, the motorway would cross the B2032 Chipstead Valley Road, and Chipstead itself, on a long viaduct across the deep valley, passing between what were then the primary and secondary schools. A service area was proposed somewhere near this point and would likely have been called Chipstead Services.

The M23 would cross Rickman Hill Recreation Ground before crossing Rickman Hill itself, cutting a broad gap through a street of established houses. It would then turn south to run parallel to the A23, around the west side of Hooley, before arriving at Hooley Interchange, modern day junction 7. Here all northbound-to-northbound and southbound-to-southbound movements would be possible.

Almost immediately afterwards would be the four-level Merstham Interchange, giving access to the Ringway 4 South Orbital Road. The M23 would then continue south towards Gatwick and Crawley.

Brighton or bust

The London to Brighton road has been associated with motoring since the nineteenth century. The Locomotives on Highways Act 1896 made it possible to drive a motor car at 14mph and without a flag bearer walking ahead of it, and its passing was celebrated with the "emancipation run", a parade of about 30 cars travelling from London to Brighton. It's commemorated annually to this day in the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run.

But this route has always been a problem. Shuffling through suburban South London, it was granted a bypass of Croydon, Purley Way, designed in 1910 (when it was justified by the "perfection of the petrol combustion engine") and open by 1924. It wasn't much, and it was derided even when it was new for passing too close to the town centre and for its shortsightedly narrow roadway.

Private investors had different ideas. A "London to Brighton Motor Way" was laid before Parliament in 1906, though it wasn't approved. Created under railway legislation, since there was no other way to make a private road for motor traffic, it would have run from Croydon to Patcham in Sussex, but lobbying from the railways and landowners saw it off very quickly.

Another private plan arose in the 1920s, from the brand new Kingston Bypass to the fringes of Brighton, complete with a tunnel at Balcombe, and survived several years before it too faltered from lack of official support.

The aspiration for a motorway never went away, though, because the A23 was a terrible road carrying an awful lot of traffic. Bressey's 1937 Highway Development Plan recommended a motorway from the fringes of London to Brighton, and in 1944 Abercrombie went a step further, drawing up plans for an "Express Arterial" road from the "B" Ring at Stockwell to the coast.

Abercrombie got the Ministry of Transport to take it seriously, and they asked Surrey County Council to come up with a detailed route. Their 1959 plan recommended a motorway from Crawley, north through Mitcham, to end on the A23 at Hermitage Bridge in Norbury. It went no further north because that was where the A23 ceased to be a trunk road, so its traffic problem ceased to be the Ministry's concern. Beyond Norbury the congestion belonged to the London County Council. Surrey's plan was not a very neighbourly one.

The M23 was included in the pledge to build 1,000 miles of motorway by the 1970s, so Surrey's sketch needed to be turned into a full set of designs. The Ministry asked consulting engineers Travers Morgan to come up with a final plan.

No end in sight

Travers Morgan mostly kept the rural part of Surrey's line, but binned much of the urban section. Everything hinged on where the M23 would terminate, and that was a problem.

We formed the opinion that neither the A.23 nor any other existing radial roads…would have the capacity to carry the traffic leaving the motorway, and that therefore even a temporary junction with the A.23 at Hermitage Bridge was not viable. [The] terminal for the motorway should be at a junction with a ring road or tangential road capable of distributing traffic concentrated on the motorway in at least two directions onto the whole network of radial roads in the existing system. Since at the time there were no such facilities existing or proposed by L.C.C., we suggested a new road between Tooting Bec and Tulse Hill which, together with the A.214, would be capable of providing some of the capacity required until an urban motorway system in London was planned and built...

Travers Morgan's "new road" was the Tulse Hill Link, a two-lane expressway from the A214 at Tooting Bec Common to the A205 South Circular Road in Tulse Hill. It would disperse traffic from the M23 to surrounding roads, though it was only expected to be temporary until the M23 was pushed further north. As temporary measures go it was a magnificently expensive and destructive one.

A public inquiry was held and legal orders were published for the M23 from Crawley to Mitcham in May 1968, but they stopped short at Mitcham because the details of the northern terminus were still uncertain.

That was because nobody really liked the Tulse Hill Link - it carved a new route through dense suburbia, bisecting Streatham town centre, and its ability to disperse traffic onto the A23, A24 and A215 would barely have matched the torrent of vehicles arriving at the end of the motorway. By late 1964 it was abandoned in favour of an extension north to meet the LCC's proposed urban motorways, an idea that required the destruction of most of Tooting Bec Common and an interchange in the middle of Balham town centre. Nobody liked that either. But in 1965 the LCC were replaced with the Greater London Council, and the GLC had a plan.

The impossible question was finally answered by Ringway 2. Once the GLC designed its motorway to replace the South Circular, the M23's terminus was simple. It would end on Ringway 2's Southern Section, a high capacity orbital that would disperse traffic on to surrounding roads and remove the need for a destructive onward extension through Balham.

A road like no other

The troublesome terminus wasn't the only problem. The M23 would be the only major, high capacity north-south route in South London for several decades until Parkway E was built, if Parkway E was ever built. Forecasts suggested the demand for travel was greater than the motorway could possibly accommodate.

The Ministry's preference was for a dual three-lane motorway, that being the maximum width their policy would allow at the time. If demand outgrew it, another motorway should be built. But in South London there was nowhere else to put another parallel motorway; the M23 occupied the only available line. So if demand was going to be higher, the road had to be wider.

The idea of a motorway with four lanes, not three, was so troubling that Travers Morgan were brought back to do another study. In August 1967 they reported that a motorway could be built with four lanes each way without causing the downfall of civilisation, but to guard against the additional risks, recommended hard shoulders on both sides of both carriageways - four in total.

They calculated that the inner hard shoulders should be 7 feet 6 inches (2.2m) wide, judged to be enough for a motorist to get out of the driver's side door and then change a wheel, something they would do just a few inches from moving traffic in the fastest lane of the motorway.

Even with four lanes the road would be overwhelmed by commuter traffic. Three ideas were considered to keep traffic moving.

One was to have no London-facing sliproads inside the Ringway 4 South Orbital Road. Travers Morgan ruled this out as being too blunt, since it would prevent the road being used to its full potential outside peak hours. The second option was tolling, which was dismissed out of hand.

The third option was "motorway management". This would take the form of equipment to dynamically open and close the north-facing sliproads when the motorway did not have the capacity to accept vehicles to or from a particular exit.

Northbound entrances would close in the morning peak, and southbound exits in the evening, to make the M23 useless for short-distance commuting to Central London. Automatic traffic counters would link to a central computer, with variable message signs and physical barriers at entrance points. If the plan had been put into place, the M23 would have been a strange and very unique motorway.

The secret extension

With design work finished, legal orders published for Crawley to Mitcham, and draft orders made for Mitcham to Streatham, the M23 was almost ready to go. But the project was paused until the end of the Greater London Development Plan Inquiry, which would rule on transport policy across the city.

The GLC's submission to the GLDP Inquiry included a map of the Primary Road Network they wanted to build - the urban motorways, in other words. It included an unexpected detail. In South London, it showed the M23 extending north of Streatham Vale to reach Parkway E at Tulse Hill.

By all accounts, the northern terminal of the M23 was going to be Ringway 2 and the motorway would go no further. The plan to reach Ringway 1 was dead. That was official GLC policy from 1966. Referring to early designs for Ringway 2, a GLC report on the M23 said:

We consider that, if it is decided to provide such a road, it should become the terminal point for the M.23 motorway.

And yet, in 1970, here was a northward extension of the M23 on the map of roads the GLC hoped to build. It pops up again, here and there, but confusingly is sometimes absent, so its status is entirely uncertain.

There's no detail on this extension beyond a line on a map, so the rationale can only be guessed at - but presumably the idea was to provide a route from the M23 through to Ringway 1, preventing radial traffic having to mix with orbital traffic on Ringway 2.

There are other hints that the GLC were keen on this idea. One is the junction numbers on the M23 today. The northernmost, at Hooley, is junction 7, meaning that six numbers were reserved for the unbuilt urban section. Six is too many for Hooley to Streatham, but it's a better fit for the number of junctions the M23 would have if it borrowed the northern part of Parkway E and ended on Ringway 1 at Loughborough Junction.

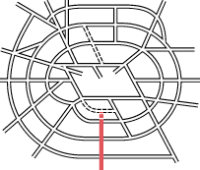

The other hint is the design of the interchange with Ringway 2. The sliproads to and from Ringway 2 are laid out to leave a clear path through the junction, which doesn't exist for any engineering or topological reason. It can only be explained as futureproofing in case the main line of the M23 needed to continue north.

Loose ends

Unlike most of London's motorways, the M23 survived the GLDP Inquiry - but Ringway 2 didn't, and nor did any of the other motorway ring roads it would have met. That turned the clock back to 1964, with a line for the motorway but nowhere to end it.

In 1976, the new Department of Transport (DTp) launched an investigation, the A23/M23 Route Study, to consider its options. A motorway was ruled out because it would concentrate too much traffic in a single corridor. Instead, an "A23 Relief Road" was considered from the M23 at Hooley to Mitcham Common, where it would split into single-carriageway link roads west to Mitcham and east to Croydon.

The report's final recommendation was even more modest: a dual carriageway from the M23 north to the A2022 at Little Woodcote, and nothing more.

In 1978, the DTp officially abandoned all plans to extend the M23 north, facing the reality that there was nowhere for it to end. Civil servants then had another think about the aimless relief road to Little Woodcote, which offered no relief to anything much, and in 1980 abandoned plans for that too.

Following a brief inquiry, legal orders for the M23 between Hooley and Mitcham were revoked. Orders for the northern terminal had never been published in the first place. Stories exist suggesting that the land safeguarded for the motorway continued to be protected until the mid 1990s, but it's not clear what for - the motorway was dead in 1978, and any hope of any road on that line vanished two years later.

Today the northern end of the M23 at Hooley still has a short length of derelict motorway pointing at the doomed northern extension.

The M23's story goes back to 1906, but the four years between 1969 and 1973, in which Ringway 2 was an active road proposal, were the only fleeting moment in its 74-year history when it had anywhere to go. Without Ringway 2, it was a lost cause, and it disappeared very quickly indeed. In hindsight it seems rather incredible that it was ever thought possible.

Sources

- Extant length of M23 opened 1974-76: Network Changes - 1970s, SABRE Wiki

- Layout of Streatham Vale Interchange; route, Streatham Vale-Hooley: Engineering plans of M23 produced by George Wimpey Ltd for borehole drilling contract, held in private collection

- Purley Way proposed in 1910; criticised for inadequate alignment and width: MT 38/36

- Purley Way open by 1924: MT 39/511

- 1906 private scheme for London-Brighton motorway: "London and Brighton Motorway" (1906) HL/PO/PB/3/plan1906/L4

- 1925 private scheme for same; tunnel at Balcombe: "Southern Motor Road" (1929) HL/PO/PB/3/plan1929/S8; HL/PO/PB/3/plan1929/S8/1; HL/PO/PB/3/plan1929/S8/2

- Bressey proposal for London-Brighton routes 25 and 61: Highway Development Survey: General Report (1937), Sir Charles Bressey and Sir Edwin Lutyens, available at MT 39/360.

- Abercrombie proposal for Radial Route 9: p73, Greater London Plan (1944), Patrick Abercrombie, University of London Press.

- 1959 Surrey CC alignment; Travers Morgan investigation and report; introduction of Tulse Hill Link; "motorway management" concept: Proposed London-Crawley Motorway: Report, R. Travers Morgan and Partners, March 1964

- Layout and route of Tulse Hill Link; abandonment of same in favour of LCC scheme to reach R1: MT 106/219

- M23 to terminate on Ringway 2 adopted as MOT policy: MT 106/219; adopted as GLC policy: MT 120/293

- Report on fourth lane and centre hard shoulders: MT 106/285

- PRN map showing M23 extending north to Parkway E: HLG 159/1024

- A23/M23 Route Study and recommendations: GLC/DG/PUB/01/362

- Abandonment of M23 and of A23 Relief Road; orders revoked: MT 152/419

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Plan of terminus on Tulse Hill Link extracted from MT 106/219.

- Photograph of M23 approaching Hooley is taken from an original by Ian Capper and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Merstham Interchange is taken from an original by Colin Smith and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Thornton Road in 1981 is taken from an original by Dr Neil Clifton and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Plan and model of 1928 scheme are from Modern Transport, 2 May 1925, and now out of copyright.

- Photograph of A23 at Hermitage Bridge is taken from an original by Robin Webster and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Diagram of centre hard shoulder extracted from MT 106/285.

- Diagram of M23 route and Tulse Hill Link extracted from Proposed London-Crawley Motorway: Report, R. Travers Morgan and Partners, March 1964.

- Plan showing M23 extending to Parkway E extracted from HLG 159/1024.

- Photograph of Woodmansterne Lane is taken from an original by Dr Neil Clifton and used under this Creative Commons licence.