A missing link that’s still missing today, the Eastern Avenue Extension was a companion to the Westway, but of a very different breed.

Plans for an “east-west route” dated back to the early 1900s, and by the 1960s the concept of a motorway linking Angel with Hackney and Eastern Avenue was well established in the planning system.

It might have been expected that the Greater London Council would scrap it, considering their policy not to build new major roads within Ringway 1 and not to encourage car commuting to Central London. But they saw its value as a relief road, taking through traffic off the jumbled streets of East London, where there was no simple main road for even essential traffic to follow. They classified it as part of the Secondary Road System and as such it survived despite the abandonment of other roadbuilding in Central London.

Keen to reduce the impact of the original plan for this major new road, and equally keen to learn from their predecessors’ experience of designing the Westway, the GLC extensively reworked and rerouted it to produce the most unobtrusive and unobjectionable urban motorway they could manage.

Their instincts were vindicated when construction of the Westway just a few years later quickly proved disastrous for the suburbs it bisected. The Eastern Avenue Extension would not be like that. But then, partly thanks to the fallout from the creation of the Westway, in the end it would not be built at all.

Outline itinerary

Ends at A501 City Road

A10 Kingsland Road

Tunnels under A1208 Hackney Road

Tunnels through Victoria Park

R1 North Cross Route and East Cross Route (Hackney Wick Interchange)

Continues towards M11 as A106 Ruckholt Road

Cost summary

| Total cost at 1970 prices | £39,750,000 |

| Estimated equivalent at 2014 prices Based on RPI and property price inflation | £594,925,000 |

See the full costs of all Ringways schemes on the Cost Estimates page.

Route description

This description begins at the western end of the route and travels east.

Angel - Hackney

The motorway would begin at Angel, today a simple urban crossroads where the A1 meets London’s Inner Ring Road. Early 1960s plans showed a three-level stacked roundabout junction here, with the A1 in tunnel, though by the end of the decade that design was abandoned and the junction was simply marked as requiring further study.

The first part of the route would probably have two lanes each way, running underneath the A501 City Road. This would continue for about a kilometre until, near Mora Street, the motorway would curve gently east.

After passing under the B144 Shepherdess Walk, it would emerge into an open trench, staying below ground level with vertical walls on either side. It would then run along the southern side of Nile Street and Bevenden Street; numerous bridges would allow the many side streets in this area to cross it. Some plans suggest that this length would have an overhang on each side, so that the trench would not be fully open to the sky.

The eastern end of Haberdasher Street would be destroyed as the motorway curved slightly to pass through the gardens at Royal Oak Court, leaving two of the residential blocks looking out over a deep cutting, and a third demolished to make way for it. The Eastern Avenue Extension would then pass under the A10 Kingsland Road immediately north of the railway bridge at Old Street.

A curve would bring it underneath the line of the A1208 Hackney Road, entering another tunnel. Above, a huge gyratory system would be formed, with streets widened to make a smoothly flowing circuit around Kingsland Road, Hackney Road, Curtain Road and Shoreditch High Street.

Sliproads to and from Hackney Road would descend into the ground, merging with the tunnel underneath, so that traffic could join the Eastern Avenue Extension eastbound and exit it westbound. This junction would serve traffic to and from the City.

From here the motorway would follow a widened Hackney Road for almost a mile to Cambridge Heath station. Below ground would be a deep trench for the Eastern Avenue Extension, while above, Hackney Road would form another dual carriageway, overhanging each side of the cutting but not entirely covering it, so for most of the time there would be an opening in the middle with the sunken road visible below.

After crossing the A107 Cambridge Heath Road, the motorway would run in deep cutting along the south side of the B127 Bishops Way. The road would then enter Victoria Park at Bonner Gate, entering a cut-and-cover tunnel to dive below the Regent’s Canal, before emerging again at the A1205 Grove Road.

Running in open cut through the northern edge of the park, past the fountain and East Lake, there would be two further short lengths of tunnel, first underneath the paths at Queen’s Gate and then the A106 Victoria Park Road. Houses on Brookfield Road and Homer Road would be demolished to clear a path through to Hackney Wick, where the road would pass underneath the junction complex before merging with sliproads from the Ringway 1 East Cross Route, joining the line of the M11 towards Wanstead.

A Hackneyed idea

Eastern Avenue dates back to the 1920s, and the concept of a main road east-west through London is older still, originating with the 1905 Royal Commission on London Traffic. The idea from the outset was simple: a main road across the central area, extending east and west to link up with new arterial roads to the suburbs and countryside.

Open by 1924, Eastern Avenue was a new road from Redbridge to Black’s Bridge, east of Romford, where it ran head-on into another new project, the Southend Arterial Road. It was intended all along that this would be a first phase, the part in open country that was easy and quick to build.

The difficult urban part would come later, but even at the road’s genesis at the 1910 Arterial Road Conferences the start point was described as “Hackney Road at Cambridge Heath Station”, with a “new street” to be built linking it to Angel.

The Ministry of Transport remained serious about finishing this “Great Eastern Road”; in 1926 drawings were produced for a single project to connect Redbridge to Western Avenue at Wood Lane, an extraordinarily ambitious route right across Central London to be built all at once. In 1945 a listing of major roads in London indicated that Eastern Avenue was due a possible extension “westward to Western Avenue: approx. 12 miles”. And in the London County Council’s 1951 Development Plan, the extension popped up again, now as a widened Hackney Road reaching in to Old Street.

New plans were drawn up for a more ambitious urban road in 1962. By 1965 it had broken into two parts: an outer length from Redbridge to Hackney Wick, which was still being pursued by the Ministry and eventually came to incorporate the M11 extension; and an inner length to be built by the new Greater London Council from Hackney Wick to Angel that would be a new dual carriageway on the line of the Regent’s Canal. The canal would be drained to provide an easy route for the new road.

Having just inherited the proposals from the Ministry, the GLC looked at this road plan - which would build a major urban road parallel to, and not far away from, the North Cross Route, and which would obliterate a canal in order to push its way through residential areas - and decided to see if there was a better way of doing things. In July 1965, just a few months after taking over, it commissioned an investigation at a cost of £25,000 to evaluate all the options.

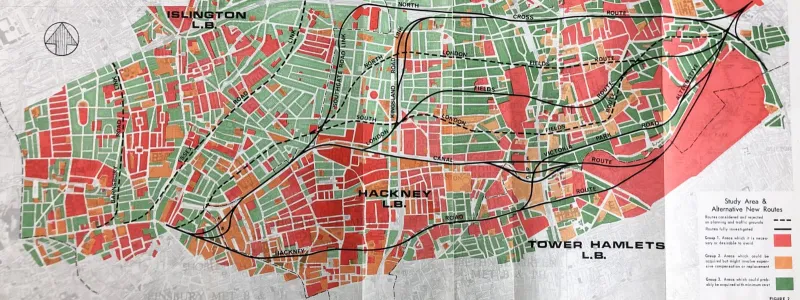

In all the study examined about a dozen routes, some quite a way off the original. Several were much shorter, travelling north to join the North Cross Route, effectively using part of Ringway 1 to avoid more urban roadbuilding.

Consulting engineers Freeman Fox and Partners produced their report in 1967, and the GLC accepted their suggestion for a very different road.

From Westway to Eastway

The route selected by the GLC was, at first sight, quite shocking. It would slice off the northern edge of Victoria Park, passing through a couple of tunnels to reduce its impact but mostly just digging a cutting through what had been open lawns. Further west, instead of following the canal, it cut an entirely new path, running beneath a vastly widened and changed Hackney Road, and contemplating an extremely unusual tunnel just below City Road.

At face value, these were terrible choices for a new road. Three times more people would have to be rehoused than if it followed the canal, and of all the options considered it was the most expensive. Ordinarily that would make it unacceptable. But the report’s authors had done their homework.

The canal was not a good place to put a road project. British Waterways hoped to make changes to create an attractive route for walking and cycling, an asset with desirable waterfront properties rather than a decaying channel of stagnant water. Recognising its potential as a rare slice of open space in East London, Freeman Fox weren’t keen on replacing it with a sunken road. Building an elevated road over it also came in for gentle criticism.

“Although this…would enable the canal to be converted for amenity use the presence of an overhead road would considerably reduce any amenity value.”

In fact the Hackney Road route offered some distinct advantages. The canal would be preserved, and plans for new housing estates adjacent to it could go ahead. Fewer objections were expected along Hackney Road since the properties there were so undesirable and many were due for rebuilding.

More to the point, the end result could be much better. Hackney Road and City Road would be extensively rebuilt, better providing for local traffic on the existing road network, while the surrounding buildings could be cleared and new developments put in their place, improving local housing and commercial stock, and including proper environmental treatments to make life near a major road more liveable.

The two double deck sections were particularly interesting. In the west, along the northern edge of the City, the motorway would be built underneath City Road. Construction would have involved closing the road entirely, digging it out to almost the full width of the street, inserting a concrete box below ground level that would be wide enough to carry a dual-two lane motorway, and then reinstating City Road on top. Whether that would be possible while retaining the existing buildings is unclear - possibly its designers envisaged clearing one or both sides of the street and rebuilding afterwards.

In the east, along Hackney Road, the cutting would contain either a dual-two or dual-three lane motorway. It would, again, be built by digging a trench underneath the existing street, but here the whole street would be widened, so everything on the south side and most buildings on the north side would be demolished. Hackney Road would become a two-lane dual carriageway, with a wide central reservation through which could be seen a motorway below. New buildings would be erected on each side, soundproofed and probably facing away from the road.

Angel’s advocate

We should pause at this point to consider the concept produced by the GLC - a sunken road, covered over in many places, surrounded by sympathetically redeveloped suburbs and landscaping - and how different it would be to the Westway, planned just a few years earlier, but entirely lacking the same concern for its surroundings. Thinking had advanced dramatically.

Today a road like that would still be considered a brutal intervention in an urban environment, but for its time it was very forward thinking. That was because the GLC was a long way ahead of everyone else on urban road design.

The “Hackney Road Route (Depressed)” option from the Freeman Fox report was approved by the GLC’s Highways and Transportation Committee, but news of their decision was most unwelcome at the Ministry of Transport.

The Hackney Road route would cost an extra £8m, and the Ministry wanted only the cheapest option to be selected. One internal memo noted, with considerable distaste, that the two routes give “equally satisfactory” engineering results, and the reason the GLC chose the more expensive one was “largely amenity”. That was dismissed as being trivialities like “noise” and “impact on the area”.

A meeting was called, at which the GLC were asked to explain their misbehaviour. They pointed out that the Hackney Road route could be built in two stages rather than one, and that property costs might reduce the overall price since the buildings on Hackney Road could be redeveloped, making way for the widened road, before work actually started. They also wanted a road that had the least negative impact on its surroundings.

Unconvinced, the Ministry demanded a review, and said any changes would have to be agreed with the Ministry of Housing and Local Government. It felt rather like they were sending the GLC to see the headmaster.

It took until June 1968 for the Ministry of Housing and Local Government to review the options. They wrote to the MOT’s London Highways Division to say they strongly supported the Hackney Road route, since it would preserve the canal as a link between leisure facilities in the Colne and Lea Valleys; it avoided dividing existing communities, which the canal route would; and it would bring much needed redevelopment to the area of Hackney Road. The GLC, in other words, were right, and the Eastern Avenue Extension didn’t have to be another Westway.

Unfinished business

The point of the motorway - foreseen right back in the 1920s - was to link the major roads of East London to the City and to Euston Road, so in that sense too it was a mirror of the Westway. Today, since it was never built, it is the only missing link in the chain formed by the A40 Western Avenue, the Westway, the A501 Marylebone and Euston Roads and the A12 Eastern Avenue.

One part was built, though, back when the first phase of Hackney Wick Interchange was put in place for the East Cross Route. Where the modern A12 approaches the unfinished junction from the east, the carriageways split apart to negotiate the railway bridges and the westbound tunnel, and two very large carriageway stubs appear in the middle. They point west, towards Victoria Park, and they were supposed to be the start of the Eastern Avenue Extension.

We’ve discussed the repeated attempts to complete this link in the 1920s, 30s, 50s and 60s. But it’s also worth saying that the concept has yet to die.

In 2014, the then-Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, unveiled plans for a 22-mile tunnelled ring road for Central London. Sudden, surprising announcements of grandiose and unlikely infrastructure projects are something of a motif through Johnson’s political career. In this instance, the intention was to free up space for development on the surface while accommodating the steep rise in London’s population that was expected.

News reports talked about a new Inner Ring Road in deep bored tunnel. But the plans showed something else, which most didn’t mention, and which hadn’t been requested when Johnson instructed Transport for London to develop the concept.

Transport planners at TfL didn’t just draw a circle around London. They drew a circle with a branch, which linked the tunnelled ring road to the A12 at Hackney Wick. They included in this plan, entirely unprompted, an underground version of the Eastern Avenue Extension.

The plan came to nothing, of course, because it was forecast to cost £30bn and there was no way to pay for it, but it still taught us one unexpected lesson. That missing link between Central London and Hackney is still bothering London’s planners even today, more than a century after it was first suggested.

Sources

- Royal Commission and East-West Route: "Report of the Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Means of Locomotion and Transport in London", HMSO, 1905.

- GLC retained EAE as Secondary Road: "A Secondary Roads Policy", GLC, 1970.

- Route and interchanges, Angel-Hackney; 1965 version of plans; GLC refer plan to Freeman Fox; report published 1967; justification for route and dispute with MOT and MHLG: MT 106/406.

- Pre-war Eastern Avenue intended as first phase with urban section to follow; description of route from 1910 Arterial Road Conferences: HLG 46/74.

- Whole route planned in 1926: MT 57/147.

- 1945 suggestion to extend west: MT 39/511.

- Inclusion in London County Council 1951 Development Plan: GLC/TD/DP/DC/43/010, and in "Administrative County of London Development Plan 1951: Statement", London County Council, 1951.

- Stubs built as part of Hackney Wick Interchange: MT 106/297.

- 2014 plan for tunnelled Ring Road; spur to Hackney: multiple reports of scheme including spur are online; one example is Murphy, J. (2014) "Mayor sets out plan for 22-mile ring-road tunnel under London", Evening Standard, 12 May.

Picture credits

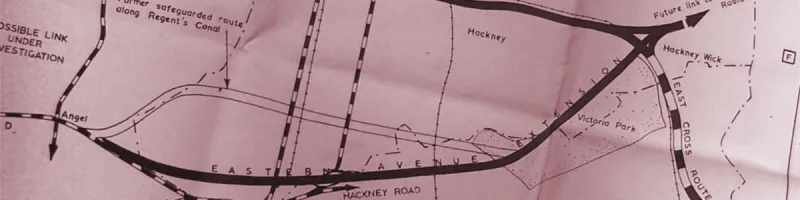

- Composite plan of all possible routes and plan of route under Hackney Road are extracted from MT 106/406.

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Outline plan showing EAE is extracted from MT 106/195.

- Photograph of City Road is taken from an original by David Hawgood and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Victoria Park is taken from an original by Paul Gillett and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Regent's Canal at Shoreditch taken from an original by Ian Capper and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of shops on Hackney Road is taken from an original by Dr Neil Clifton and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Acton's Lock is taken from an original by Robin Webster and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Image of carriageway stubs at Hackney Wick © 2023 Google.

- Diagram of 2014 tunnel proposal was released for publicity use by Transport for London.