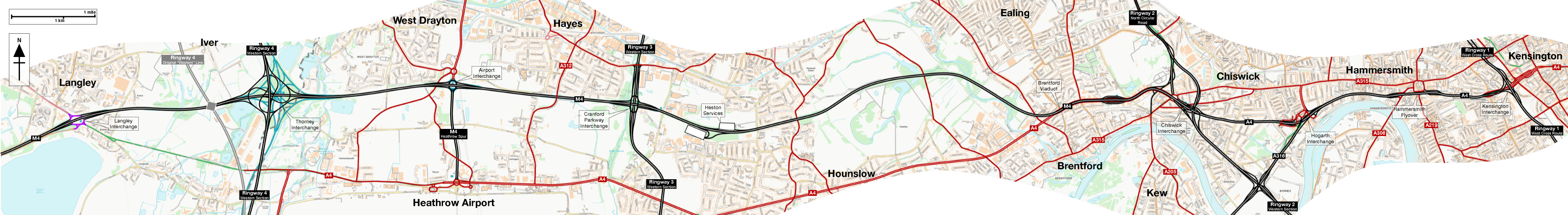

Serving Reading, Bristol and South Wales, the A4 and M4 are one of London's most important approaches. But the wildest fantasies of the sixties couldn't overcome its trickier problems.

Long before improvement work was ever contemplated for most of London's roads, the A4 needed special attention with a lengthy bypass of its worst bottleneck. Improved and extended over the following decades, a whole new route into London was progressively built. Just as it was completed in the early 1960s, it was bypassed again, this time by the new M4.

The M4 did a great deal to improve the journey west, whether motorists were heading for Cardiff or just to Heathrow Airport. But it included a fatal weakness that continues to plague the route even today.

At the London end, the M4 transitions from a dual three-lane rural-standard motorway to a claustrophobic two-lane elevated road suspended above the A4. This design choice ended up seriously limiting the ambitions of 1960s motorway planners, and will likely continue to limit the capacity of this route for all time.

Further in to London, plans for the A4 seemed straightforward, and by 1965 the requirement for a continuous two- or three-lane route from the M4 to Ringway 1 at Kensington appeared to be achievable. But uncertainty about how the remaining work could be done was hanging in the air right up to 1973, when all London's motorway plans were dropped.

This is a route where nearly everything that was planned in detail exists and can be driven today, but it's not without interest. The highlight is one of the most unlikely road projects ever proposed, in the form of an extended M4 where traffic would run on the wrong side of the road to traverse the whole of London. Needless to say, the idea didn't get far.

Outline itinerary

Continues to Slough and Reading

R4 Western Section (Thorney Interchange)

A408 and Heathrow Spur (Interchange)

R3 Western Section (Cranford Parkway Interchange)

R2 Western Section and R2 North Circular Road (Chiswick Interchange)

Local connections to Chiswick

A316 (Hogarth Roundabout)

A219 Hammersmith Broadway (Hammersmith Flyover)

B317 North End Road

R1 West Cross Route (Kensington Interchange)

Route description

This description begins at the western end of the route and travels east.

Iver to Kensington

Heading in to London from the west of England, the M4 already existed when London's Ringways were announced to the public, so this part of the route is no mystery. A four-way junction at Thorney would connect to Ringway 4's Western Section, close to modern-day junction 4B, though it would initially comprise a large three-level roundabout junction, with space for extra sliproads to convert it to free-flowing operation.

Continuing east, Airport Interchange (M4 junction 4) would connect to an improved Secondary Road north to Uxbridge, broadly on the line of the modern Yiewsley Bypass, and a spur south to Heathrow Airport. The next interchange, Cranford Parkway, would be converted to a three-level roundabout and would be the crossing point for Ringway 3's Western Section.

Shortly afterwards, Heston Services provides facilities precisely 12 miles from Central London, as per the Ministry of Transport's policy on motorway service areas in London. The road would then narrow from three lanes to two and the speed limit would drop as the road entered Brentford, running at the upper level of a double-deck road structure with the A4 below. All this exists today.

At the Chiswick Roundabout, a massively expanded interchange with free-flowing sliproads would link the M4 to the west with Ringway 2's North Circular Road and Western Section. The M4 would terminate here, and the A4 would continue the journey in to London as a three-lane dual carriageway.

Sutton Court Road would cross on a flyover, eliminating the traffic signals, and the A4 would bridge Hogarth Roundabout, serving the A316 from the south west. Large volumes of traffic would join the route here.

At the A219 Hammersmith Gyratory, one lane would peel off, and the remaining two would traverse the Hammersmith Flyover, rejoined by a third lane on the final approach to Kensington. The traffic lights at Gliddon Road would have been eliminated, though no plans have come to light for this junction.

Approaching the B317 North End Road, the carriageway would split, with two lanes rising to an upper level, avoiding the traffic lights. The A4 would continue at ground level, now a Secondary Road, and motorists wanting to continue in to Central London would stop at the lights before continuing along the A4 as it exists today.

Large volumes of traffic were expected to exit here, taking the upper level sliproad which would run above the A4 for a short distance before a free-flowing elevated junction with the Ringway 1 West Cross Route, and ending the A4's journey as a part of London's Ringway network.

Go West

The ancient coaching route known as the Bath Road became the A4 when road numbers were handed out in 1922, but such is its importance that it already incorporated the UK's first motor-era bypass. The initial section of the Great West Road opened to traffic in 1914, and was progressively extended until by 1925 an eight-mile road bypassed the narrow and easily-blocked High Street in Brentford.

The worst bottleneck was gone, but the rest of the road still needed urgent work. Completed over subsequent years, and still actively under construction in the 1950s, was Cromwell Road, an eastward extension of the Great West Road providing a southerly bypass of Chiswick, Hammersmith and Kensington. It's hard to believe now, but the whole modern A4 from Knightsbridge to Hounslow is a new road.

After the Chiswick Flyover opened to traffic in 1959, the missing piece in this epic project was the Hammersmith Flyover. Opened in 1961, almost half a century after the first length of Great West Road, it takes the A4 over the top of Hammersmith town centre. This ambitious and remarkable 16-span viaduct carries four lanes of traffic at rooftop height for nearly half a mile.

It was unprecedented in the UK when it was built, and despite suffering problems in the recent past thanks to its age and experimental design, it remains an astonishing reminder of just how much effort went in to improving the A4. Its completion meant the road had been comprehensively improved from Hyde Park to rural Buckinghamshire.

The Hammersmith Flyover might have completed the job but problems remained. The purpose-built arterial road of the 1920s and 30s was now built up, a slow drive through suburbia. Parts were famed for it - near Brentford was the "Golden Mile", lined with factories showcasing some of the UK's most stylish art deco architecture. A better way to Heathrow Airport was needed, and the new national motorway programme would provide it, bypassing the Great West Road.

Planning for the Chiswick-Slough length of M4 was well under way by 1957, before any motorways had actually opened in the UK, so this was a very early priority. From the outset an elevated road was planned above the A4 at Brentford, but initially consultants considered building the whole motorway like that, right out through Hounslow and past Heathrow Airport. The question was whether the upper deck, carrying the motorway, should have two lanes each way, or whether it should be a single three-lane carriageway, with a shared overtaking lane in the middle.

M4 better or worse

The naive single carriageway option was soon ruled out - an engineer's report stated it would be "regretted in a very few years" - and the current route of the M4 was selected. In November 1958, discussions were ongoing about how to build a viaduct that could carry three lanes each way.

The rural M4 would have three lanes each way, of course, so continuing them to its terminus at Chiswick was eminently sensible. But engineers found that suspending six traffic lanes above the A4 was much harder than four. A four-lane viaduct could be supported on a single line of piers in the middle of the Great West Road, but a six-lane structure needed pillars down both sides, requiring the relocation of all the underground utilities. It cost an additional £2m, a large sum at the time.

The clinching argument, though, was that the route would incorporate the Chiswick Flyover, which already existed and carried two lanes each way. There was no point providing three lanes when the motorway would have narrow to two anyway.

No matter, said the engineers: traffic moving at 70mph leaves long headways between vehicles. Slow it down to 40mph and the headways are shorter, so the same number of vehicles can fit into a smaller area. A two-lane viaduct could carry the traffic load of a three-lane motorway… in theory.

In practice, it can't. The eastbound queues that form every day, all day, on the M4 at Heston are a testament to that.

Construction of the viaduct was an ordeal. The roadworks were described by The Guardian as "intense agony", and the Ministry took the remarkable decision to issue the stark advice "don't go west" for the duration of the works. And the trouble didn't end when the road opened, because it quickly became clear that two lanes were inadequate.

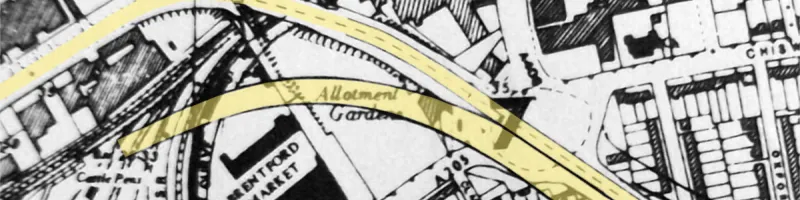

Widening the viaduct is an impossible task, but in 1969, just five years after it opened, and with its shortcomings already apparent, the Greater London Council thought it could be bypassed. A few rare plans for Chiswick Interchange show the Brentford Viaduct carrying only eastbound traffic, and point towards a new westbound M4 built along the parallel railway line.

Whether this intent was shared by the Ministry is unclear, but in 1973, the Layfield Report mentioned that the M4 had reached "the limit of possible improvements", having heard evidence from a Department of the Environment official who told them that widening or duplicating the elevated section would be "prohibitively expensive and destructive". Traffic would instead be encouraged to use other radial routes, a rather sad outcome for a road not yet ten years old.

With the M4 open, attention turned back to the A4 east of Chiswick - built in the 1950s but already inadequate. The MOT had responsibility until a point just west of Hammersmith, and from there to Central London the GLC took over.

On the Ministry's length, there were really only two problems: the roundabout at Sutton Court Road (now a set of traffic lights), where a straightforward flyover was designed in 1966, and the Hogarth Roundabout, the connection to the A316. Sir Bruce White, Wolfe, Barry and Partners, a firm of consulting engineers, were recruited in 1965 to suggest a temporary fix for Hogarth and a permanent scheme to be built later.

Pigs might flyover

Their immediate advice was straightforward: build a temporary flyover from the A316 to the eastbound A4, removing the main cross-traffic from the roundabout. Plans were delivered to the Ministry and the Ministry were pleased.

Suggestions for a permanent improvement were more questionable. In their 1967 report, the consultants made a series of proposals, not all of which were compatible with the brief they'd been given.

Their suggestions were:

- A curved flyover for the A4 with a small roundabout underneath, requiring minimal property demolition.

- A longer flyover for the A4 with a bigger roundabout underneath, requiring more demolition, but with potential to form part of a longer elevated road.

- An extension of the M4 east from Chiswick, above the A4, until a point east of the Hogarth Roundabout. Another crossover junction like M4 junction 2 would be provided near Sutton Court Road.

- An extension of the M4 as above, but travelling further, running parallel to the Hammersmith Flyover and finishing somewhere around Baron's Court.

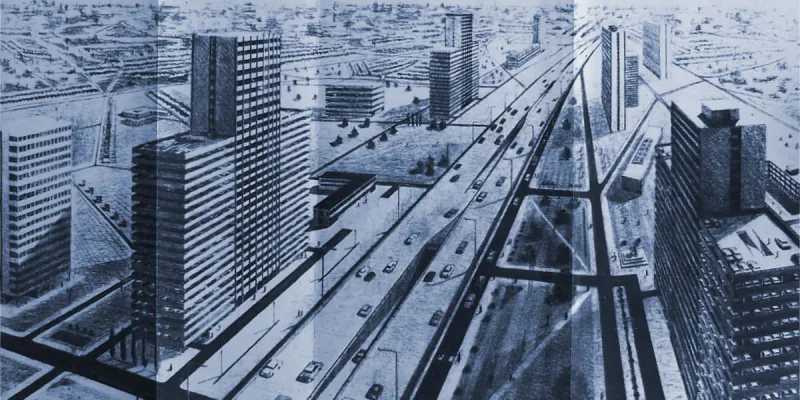

- An extension of the M4 using a novel "Centre Slot Elevated Road" system, where traffic on the upper level would run on the right hand side, and sliproads between the upper and lower levels would rise and descend through the middle of the structure (hence the name). This would involve crossovers to right-hand running at each end. It would run from Chiswick to a point east of the Hogarth Roundabout.

- An extension of the M4, using the "Centre Slot" system, but now continuing past the Hogarth Roundabout, parallel to the Hammersmith Flyover, along the A4, and then - in what appears to be a complete abandonment of the project brief - along Piccadilly, Shaftesbury Avenue and Holborn, through Bank junction in the City, and then out again on the A13, terminating somewhere near Barking.

Barking was both the terminus of the final proposal, and also an apt description of it. But the consultants seemed optimistic that the Hogarth Roundabout flyover project would usher in a new era of traffic flowing across London at rooftop level on the wrong side of the road, and had built models of the Centre Slot structure, stress testing them in laboratories at Imperial College.

Needless to say, all but the first two ideas were not just beyond what the MOT had asked for, but was also beyond what the MOT could do, since their responsibility for the A4 ended half a mile east of the roundabout in question.

The simpler flyover plans were preferred by civil servants. It would have been understandable if they had decided someone less prone to wild flights of fancy should design it, but they allowed Sir Bruce White's firm to continue, and in 1971 a further report was supplied to the Ministry. This one was mercifully free of wacky ideas for cross-London roads with wrong side driving, and instead made various proposals for Hogarth Roundabout itself. In some the A316 would free-flow into the A4, in others the roundabout would stay and the A4 would get a flyover or underpass. In many of them a new link road would be pushed through the houses to the north of the A4, forming a through route to Goldhawk Road.

It's not at all clear, at this stage, which of the many competing designs was preferred for Hogarth in the end. The text of the 1971 report has not survived, and neither has the Ministry's response to it, so we are just left with a pile of possible layouts. Complicating matters is a further layout that turns up in the evidence submitted to the Greater London Development Plan Inquiry in 1972, a year later, which is different again. The 1972 plan shares some elements of the 1971 designs, though it doesn't exactly match any of them, and is the latest version available, so it is the one depicted on the map at the top of this page - though, in truth, it's quite possible that a different design was preferred for Hogarth Roundabout. We may never know. The permanent flyover scheme came to nothing.

The temporary flyover opened to traffic in 1971, at which point all progress seems to have stalled. The reason appears to be very simple. Before making any final decisions about Hogarth, civil servants in Whitehall wanted to see the outcome of the GLC's study into their section of A4. It would reveal the capacity of the road inward from Hammersmith and inform the type of improvement that would be appropriate. It was even possible the GLC would recommend extending the M4 in to Ringway 1, which would recast all the plans for this junction: such a possibility was hinted at in an engineering report for Ringway 1's West Cross Route, though it wasn't considered a likely outcome.

In 1973, of course, the incoming Labour administration at the GLC cancelled all the council's road plans, which meant that there would be no Ringway 1 and no further capacity upgrades to the A4. With no new capacity between Hammersmith and Kensington, and nowhere to terminate a faster, wider road, the Ministry decided the temporary flyover would suffice for now. It has sufficed ever since, and is still there today, a little reminder that the A4 isn't finished, and never will be.

Sources

- Junction layout at R4: MT 120/234.

- Junction layout at R3: GLC/RA/D2G/03/083.

- Sutton Court Road flyover: GLC/TD/PM/CDO/07/098.

- Junction layout at R1: GLC/TD/DP/LDS/02/098.

- Great West Road and opening date: MT 39/511.

- Early planning for M4; route above A4 to Heathrow; single carriageway upper deck; discussion about six lane viaduct at Brentford: MT 95/309.

- Viaduct construction and advice "don't go west": MT 121/135.

- GLC plan showing second viaduct at Brentford: GLC/DG/AR/6/093.

- DoE evidence to Layfield panel that M4 would not be widened: HLG 159/626.

- Consultants' work on Hogarth Roundabout and centre slot system: MT 118/251, GLC/TD/PM/CDO/07/096, GLC/TD/PM/CDO/07/097.

- Compulsory purchase of houses on Dorchester Grove: MT 139/212.

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Artist's impression of Centre Slot flyover system and photograph of Hogarth Roundabout in 1966 extracted from MT 118/251.

- Photograph of the closed M4 at Boston Manor appears courtesy of Ian Mansfield and is taken from an original on IanVisits.

- Photograph of M4 under construction in 1964 is taken from an original by Clive Warneford and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Hammersmith Flyover is taken from an original by Richard Cooke and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Great West Road in 1949 is taken from an original by Ben Brooksbank and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Aerial photo of Great West Road is courtesy Britain From Above, EAW013190. © Historic England. Used under the "blogging use" licence terms.

- Photograph of Brentford Viaduct under construction is extracted from MT 95/726.

- Plan showing M4 westbound joining railway line at Brentford is extracted from GLC/DG/AR/6/093.

- Four 1971 plans for Hogarth Roundabout are extracted from GLC/TD/PM/CDO/07-097.