The previous two pages explain how road numbers all fit neatly into a system. This page is here to tell you that they don't.

Any description of the road numbering system will tell you the UK is divided into numbered zones, and roads within those zones take the first digit of their number from the zone they are in. A good description will mention that a different set of zones exist for motorways. A really good one will include the additional rules for allocating the rest of the digits according to the road’s proximity to the hub.

Few descriptions of the numbering system will tell you that nobody has paid much attention to those rules for the last 80 years, and that even where they are rigidly observed, there are countless exceptions and deviations that complicate everything.

Why? Because numbering is usually considered an afterthought, and often decisions are taken by people who don’t know, or don’t care, that there is a system at all.

Time to go through the rules again, from the top, and find out what really happens.

Single-digit A-roads form zone boundaries

Mostly they do, but there are plenty of exceptions. Sometimes a geographical feature forms the boundary - the Thames between zones 1 and 2, and Solway Firth between 5 and 7.

Occasionally there’s no single-digit A-road in the right place. In Central London, for example, A1 to A5 don’t actually all meet, so the A40 forms the boundary between zones 4 and 5 from Marble Arch to St Paul’s, and the boundary between 1 and 4 from there to Bank.

Zoom in even closer and it becomes apparent that many roads have now been declassified within the City, so that the zones are effectively undefined once you get inside the Square Mile.

In Edinburgh, zones 1, 6, 7 and 9 meet in the city centre. Three of those boundaries are formed by the A1, A7 and A8, but there also has to be a boundary between zones 1 and 9, which is marked in its entirety by the A900.

Incidentally, between Edinburgh and Newhouse, the A8 forms the boundary between zones 7 and 9, because zone 8 can only begin when the A9 branches off it. But the A9 hasn’t branched off it at all since Edinburgh Airport had its runway extended in the early 1970s, and the first part of the zone 8/9 boundary is now loosely marked by the M9 until the A9 finally starts near Grangemouth.

These things aren’t even new. In the original scheme, in 1922, the A4 ended at Bath, such was the dogged insistence that it should correspond to the ancient Bath Road. Between Bath and Bristol the boundary between zones 3 and 4 was continued by the A36. The A4 was only extended all the way to the shore later.

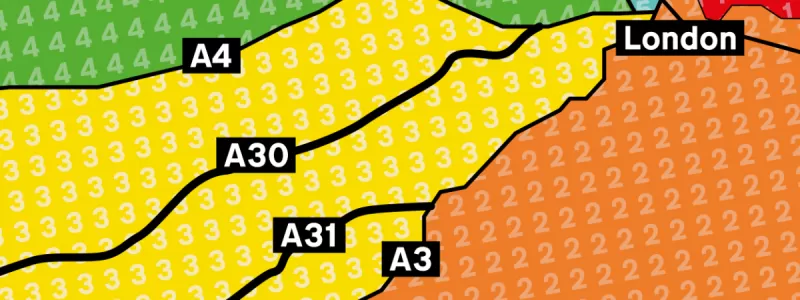

Then there are the locations where the single-digit road has been shifted off the boundary. Right back in the 1920s, the relocation of the A3 to follow the new Guildford and Godalming Bypass was accompanied by a decision that the zone boundary should not move, so between Burpham and Milford in Surrey, the A3100 is the boundary, not the A3.

However, there’s never been any consistency over what happens to the boundary when the road that marks it is redirected. Near St Albans, the A5 and A6 were downgraded so a pair of four-digit A-roads now mark those boundaries.

Around Newcastle, the A1 shifted east into the Tyne Tunnel in the 1960s with few ripples being made. Then, two decades later, the A1 moved again to the new Western Bypass - and this time the boundary did move, triggering a mass renumbering to put the whole of Newcastle and Gateshead in zone 1. This exercise was so zealous that it even got rid of several 6-zone roads innocently crossing the A1, something they are permitted to do, and instead cut them short at the zone boundary. As a result many (but not all) roads approaching Newcastle from the west now exchange their zone 6 number for a zone 1 number when they cross the bypass.

There are similar boundary problems on the motorway network. Regardless which of the conflicting schemes for motorway numbering zones you prefer, some of the boundaries are either formed by arbitrary straight lines or by following other roads like the A1.

Two-digit A-roads radiate clockwise from the hub

In the 1920s there was a lovely idea that the lowest two-digit roads in each zone would be additional radials from London and Edinburgh - so, in zone 1, the architects of the scheme assigned A10, A11, A12 and A13 in clockwise sequence, striking out from London in zone 1. Descriptions of the system often mention it.

They did the same in zone 2 (A20, A21, A22, A23, A24). Then, in zone 3, they were overcome with sentimentality.

The first radial within the zone, working clockwise, branches off the A3 at Guildford and runs down to Dorset. The second, further around, starts in Hounslow and runs to Basingstoke, Exeter and eventually Penzance.

The first should be A30 and the second should be A31. But it was decided that the Penzance road was the more culturally and symbolically important one, so the numbers were reversed to give it the more important-sounding number. As a result, the A30 goes to Penzance even though it was knowingly allocated out of sequence by the very people who made the rules.

Three-digit A-roads have lower numbers nearer the hub

You can look at a map and find that, for the most part, consecutively numbered three-digit A-roads will all be found in the same region, and that the numbers get higher as you move further from the hub. But even in the 1920s that was too restrictive to be applied across the board.

In the 4-zone, the idea was abandoned just five numbers in. A400 to A409 are found in the western and north-western suburbs of London, starting with the first four which all radiate westwards from the centre. But in the middle of the group two numbers were reserved for roads in the wrong place: the A405 was held in reserve for the North Orbital Road, out in Buckinghamshire among the A410s, while A406 was earmarked for the North Circular Road, closer to the hub than A405, but further out than A407. Presumably someone just liked those two numbers.

Important roads have shorter numbers

Some of them do, many of them don’t. This principle was easy to follow when the system was first being created, but as soon as changes began to happen and new roads began to be built, it was almost impossible to preserve.

Take the UK’s first new-build inter-urban highway, which was the Wolverhampton-Birmingham New Road. Forming a new main road between those cities, it was an improvement over the parallel A41, but the 4-zone had no short numbers left, so the important new road got the unimportant number A4123.

The next major inter-urban road was the East Lancashire Road, connecting Liverpool and Manchester. Its three-digit number, A580, makes it sound less consequential than the slow and unimproved A57 between the same two cities.

This happens an awful lot, often because the most important roads are a priority for replacement with better facilities. When the M4 was completed across England in 1971, it rendered virtually the whole A4 obsolete, so that single-digit A-road is a backwater for most of its length. More recently, the construction of a dual carriageway across Anglesey took the form of an extended A55, and is now far busier and more important than the A5 which runs right alongside but is little more than an access road for a series of towns and villages.

Roads crossing boundaries follow the anticlockwise rule

Roads don’t always stay in their own zone, so a rule exists that says roads crossing boundaries take their number from the furthest anticlockwise zone on their route.

This is fine in principal but has proved thoroughly dispensable when it became inconvenient.

Most of the roads that break this rule do so because they have been extended, and extensions are nothing unusual: if you have a useful and well-recognised road, you might like to capitalise on that by making it go further. Roads from zone 3 like to travel a lot, mostly thanks to this process.

The A34, for example, started life as the Winchester to Oxford road, but then got a bit carried away in the wide-ranging 1935 numbering review, ploughing onward to Birmingham and then Manchester. Its northern terminus is now in Salford. Meanwhile, the A38 is the UK's second longest classified road (after the A1), initially being an ambitious route from Plymouth to Derby before gaining extensions at both ends to become the positively astonishing Bodmin to Mansfield road. The A361 did likewise to become the scenic route between Ilfracombe, Devon and Kilsby, Northamptonshire.

The problem with this is that an extension might carry a road across a zone boundary, and by the middle of the twentieth century the emphasis was on retaining a suitably important number. The A66 is a good example, initially starting on the A6 at Penrith and running east to Scotch Corner and beyond. In the seventies it was extended west across the A6 and into the Lake District. It should now have a zone 5 number, but A66 sounds better, and avoided renumbering a lot of well established road east of the A6, so A66 it remains.

A similar trick was pulled off with the M62, originally intended to start at Manchester and travel east over the Pennines. While it was under construction the M52 Liverpool to Manchester motorway was absorbed to form almost a coast-to-coast motorway, with the result that the M62 is out-of-zone at its Liverpool end.

Each road number occurs only once

If you are directed to follow the A316 then, once you find it, you should be confident that you’re in the right place: there should only be one A316 anywhere in Great Britain. Unfortunately, for that to remain absolutely true would require better organisation and record-keeping than has ever been achieved by the people in charge of road numbering.

As a result, the UK has an interesting collection of duplicated roads, and this is not even beginning to consider that there are separate roads called A1 in Great Britain, Northern Ireland, Jersey and Man.

SABRE keeps a close watch on road numbering, and at the time of writing lists 37 duplicated A- and B-roads in Great Britain, and three more in NI. Almost all are the result of some sort of bumbling clerical error.

Take a visit to Leicester and you can enjoy a ride on the A594 Leicester Central Ring Road, built in the sixties and seventies to carry traffic around the city centre. I know what you're thinking, though: it's very urban, isn't it? Very built up? Not to worry; if you don’t like this A594 then we can go look at the other one. Motorists who tire of circling Leicester and pine for fresh air and scenery should choose the A594 from Maryport to Cockermouth in Cumbria. It's been there since 1922 (and was once much longer, before the A66 made its westward lurch) but that didn't stop someone mistakenly applying the number a second time in the East Midlands.

Broadly the same story explains most duplicates. Look hard enough and you'll find that as well as the B198 Lieutenant Ellis Way in Cheshunt, there's also a much older B198 running all the way through Wisbech. The B5444 crops up in both Swansea (in the wrong zone) and Mold (in the right zone), but not in between. There's plenty more.

A different kind of duplication happens where a long road is broken into parts, leaving multiple isolated lengths with the same number.

The usual culprit is a new motorway. The old road alongside it will be renumbered or downgraded completely, but only for the length that has been replaced, and sometimes not even for that. The M5, for example, relieves the A38 all the way from Birmingham to Exeter, but only south of junction 27 has the A38 been disguised as the B3181. The A38 is now effectively two separate roads, one from Bodmin to Exeter and then Sampford Peverell to Mansfield.

A more thorough effort was made by the M11’s designers. The old A11 was put through a bacon slicer to create a whole collection of new roads, becoming variously the A104, B1393, A1184 and B1383, not to mention some unclassified parts. It leaves a still-important A11 running from the M11 in Cambridgeshire to Norwich, and another more obscure A11 covering a few miles of road in East London. Much the same was done to the A47 with the arrival of M6 and M69 across the Midlands, leaving the old A-road with a gap between Birmingham and Leicester.

Road numbers are allocated according to the system

Lots of them are. Some of them aren’t. This is the uncomfortable truth that students of the road numbering system prefer not to mention: nobody responsible for numbering roads cares as much about the system as we do.

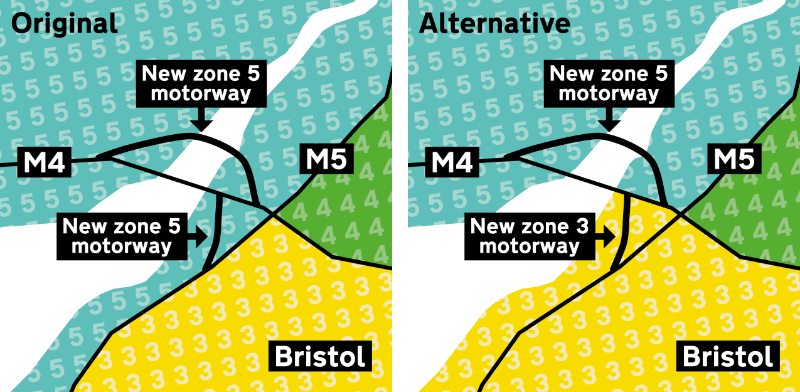

The best illustration is found near Bristol and concerns the motorway zones. This is a complex location: motorway numbering zones 3, 4 and 5 meet at Almondsbury Interchange, where the M4 and M5 cross, though the exact arrangement of zones here will vary depending which version of the motorway numbering system you prefer.

In 1996, the opening of the Second Severn Crossing (now the Prince of Wales Bridge) saw the M4 diverted onto a new route, leaving its former alignment across the Severn Bridge in need of a new number. As part of the same project, a motorway linking the new bridge to the M5 was created, requiring a second new number.

According to the original 1960s system, both would be in zone 5. According to the later system, one would be in zone 5 and the other in zone 3. Both zones, of course, have plenty of vacant numbers.

So what were these new motorways called? Why, M48 and M49, of course.

You can perform some theoretical gymnastics, if you wish*, to argue that M48 used to be M4, so a zone 4 number might be acceptable. You could even argue that the M49 is the only actual evidence for motorway numbers south of the M4 and west of the M5, so that must be somehow part of zone 4. The devil can cite scripture for his purpose.

The reality is probably more mundane. Nobody building motorways in the early 1990s was constructing elaborate arguments to twist the logic of the motorway numbering system. The likelihood is that there were few, if any, people involved in the project who would have any knowledge that a motorway numbering system had ever existed, and the policy developed for that purpose in the early 1960s would have been fading fast in the Department of Transport’s institutional memory.

The M48 and M49 don’t fit the motorway zones because the people who chose them weren’t interested in numbering. They wanted two numbers that seemed about right for their surroundings. They both meet the M4, so they begin with a 4. One meets the A48. Job done.

All over the UK you can find numbers that break the rules without looking monstrously out of place, because they were allocated by someone with no knowledge of the system who just chose something that looked about right. Usually that works OK, because most people don’t think twice about road numbering. But it doesn’t half cause sleepless nights for those of us who do.

Road numbers begin with A, B or M

Not even close.

The government, cartographers and highway engineers are part of a conspiracy. Yes, numbers that are part of Great Britain’s national numbering scheme are always prefixed by A, B or M. But many other roads in the UK - including bridlepaths, footpaths, green lanes, byways and other public rights of way - are also numbered.

Local authorities use the other letters of the alphabet to assign numbers for their own internal reference, making it easier to identify which High Street needs resurfacing or which Station Road has a light out. Most commonly these are C-, D- and U-roads. All are considered unclassified, since they are not numbered for Classification purposes, and the numbers are not supposed to be public. As a result you shouldn't see them on signs. They are unique only within each highway authority's boundaries, and they may not form logical routes.

The extent to which these exist is quite phenomenal. One report suggests that Devon County Council keeps such a close watch on the rights of way under its control that it uses virtually every letter in the alphabet, including X, to number the different types of track, back lane, cul-de-sac and footway that it maintains.

Occasionally these odd numbers do appear on road signs by mistake. Roads.org.uk has a photo gallery of locations where this has happened.

* Previous versions of this page did just this, with an extended explanation of how the numbers M48 and M49 could be justified with enough bending of the rules. But we’ve trimmed most of that out of this rewritten page since it obscures the uncomfortable truth about why these numbers were chosen.

Picture credits

- Photograph of C264 sign to Belfast is taken from an original by Jonny boy and used with permission.

- Photograph of Waterloo Place in Edinburgh is taken from an original by Thomas Nugent and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Map of Newcastle is extracted from Esso Motor-Map No. 5 Northern England (1985), and is a limited extract used for review purposes.

- Photograph of A55 on Anglesey is taken from an original by Ian S and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of A38 in South Normanton is taken from an original by Lewis Clarke and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of A594 Waterloo Way in Leicester is taken from an original by Mat Fascione and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Map of A11 and M11 near Bishop's Stortford is taken from Bartholomew National Map No. 16 Essex, Copyright John Bartholomew & Son 1975, and is a limited extract for review purposes.

- Photograph of C278 sign is taken from an original by Clive Jones and used with permission.

Sources

- Zonal system uses Thames, Solway Firth: MT 39/241

- A40 as boundary C London: "A40/Central London - Denham", SABRE Wiki

- A900 as boundary Edinburgh: "A900", SABRE Wiki

- A36 as boundary Bath-Bristol in original scheme: visible on OS Ministry of Transport Road Map Sheet 32 (Bristol and Cardiff) 1922-23, available on SABRE Maps

- A3100 as boundary Guildford, Newcastle changes: "Numbering anomalies - Move of zone boundary", SABRE Wiki

- A34 extended in 1935 review: MT 39/246

- M52 absorbed into M62: "M52", SABRE Wiki

- Numbers used more than once: "Duplicated road numbers", SABRE Wiki

- Motorway zones around Bristol: MT 112/67; Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions information leaflet referenced at "The UK Road Numbering System", SABRE