Road numbers involve a world of zones, boundaries, rules, conventions and intricacies. Who was behind all that detail, and why did they think it was important?

Today we take road numbers for granted - they’re just there, and they have been there for a hundred years, which means that none of us have ever known a world without them. But it’s interesting to step back and ask just why roads were ever numbered. Why hubs and spokes? Why A and B? Who thought it all up? And how are numbers devised and applied today?

The story of classification in the UK is not quite as straightforward as it might be - disrupted by war, complicated by a French industrialist and sabotaged by cartographers. This is the story of how the Men from the Ministry came up with an awful lot of numbers.

A world without numbers

Since humans first inhabited the British Isles there have been roads, but they all looked much the same and it was often difficult to tell them apart. That didn’t matter too much until the early twentieth century, when motor cars appeared and the demands being placed upon city streets and country lanes began to change enormously.

Local authorities found it difficult to keep track of maintenance work. Central government had no accurate measure of the distances between towns. Travellers lost their way because one road was much like another, and road signs were generally poor.

In 1910, with motor traffic rising, action was taken to sort out the mess. A government body called the Road Board was set up under William Rees Jeffreys. He was instructed to upgrade existing roads and build new ones using money from the new ringfenced road and petrol tax.

The trouble Jeffreys and his colleagues faced was in working out where to spend their enormous budget.

There was nothing to tell roads apart and no data to say which roads were busy. Information was needed and, in 1913, work to gather it began under Sir Henry Maybury, one of the Board's senior engineers. The task was to classify each road depending on its traffic level. Once classified, roads could also be assigned numbers for reference. A document from about 1914 explains:

"The object of numbering roads under the scheme for the classification of roads is obviously for the purpose of easy reference between the Central Department and the Local Authorities and others.

"The proposal is to give a road one reference number from its commencement to termination; e.g. the Great North Road from London to Inverness will be given one number throughout its entire length.”

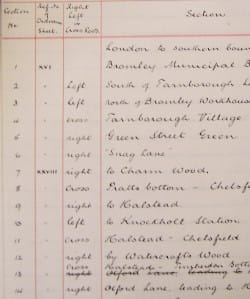

This concept evolved, so that each road was split into numbered sections. A new section would begin at each road junction, and the location of maintenance work could then be identified as being at "5-315", that being section 315 of road 5.

A circular was sent to all County Councils in April 1914 asking them to commence traffic surveys so that classification on this basis could begin, and a sample scheme for Kent was drawn up.

The intention right at the beginning was for three categories - Class I and Class II, for the two busiest groups, and everything else being regarded as “unclassified”. But the nature of the numbers kept shifting, and after a while numbers would be specific within individual counties, so roads would gain a new number when they crossed county boundaries.

The outbreak of the Great War in 1914 brought all work to an abrupt stop. It was only in September 1919, as affairs were returning to normal, that Sir Henry was invited to resume his classification work, now under the Ministry of Transport.

Men of letters

Setting up the new Ministry took time. When enough staff became available for the project, Sir Henry and his colleague Colonel Richmond wrote again to County Councils asking them to perform traffic surveys on all their roads and return the data so that classification could begin. This work got under way in 1920. The system of Class I and Class II roads was retained, but there was now a new concern, which was that road numbers might be useful for navigation. With this in mind the idea of duplicating numbers in each county was scrapped.

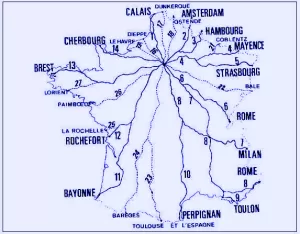

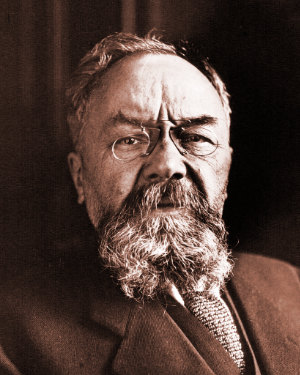

It's hard to say how influential the Michelin company was in the numbering system that was eventually adopted, but it was certainly influential in most areas of motoring in the early twentieth century, and André Michelin himself (its founder) took a great and personal interest. He wrote four papers on the subject of French and British road numbering, specifically for the Ministry's attention, explaining the French system and proposing a system for Britain.

Michelin suggested numbering main roads from London, and other key cross-country routes, as “National” roads, with the letter prefix N - much like in France. Those radiating from London would count clockwise, and the rest would be numbered from north to south. There couldn’t be too many N-roads because they would be contrived to divide the country into exactly 24 sectors.

"Each sector would be distinguished by a letter of the alphabet (except the letter "N").

"All the first class roads in a sector would be given a capital letter as allocated to the sector, followed by a number (Example: A49, H54). All the second class roads in the sector would be given a serial number followed by a lower case letter as allocated to the sector (Example: 59a, 54h)."

Sir Henry Maybury, in receipt of all this, thanked Michelin for his trouble. Nothing further appears to have ever been said about it at the Ministry.

As the survey results came in, maps were marked up to show which roads carried enough traffic or connected sufficiently important places to be regarded as Class I, and which were Class II. The initial proposal was to use the letter prefixes T and L when allocating numbers for navigation - standing for "Trunk" and "Link" - but that was soon replaced by the idea of simple A and B designations. The letters A and B don't stand for anything in particular. It's more like a school report where the best roads are awarded grade A, and the smaller connecting roads dread parents' evening because they only got a B.

Interestingly, T and L did survive a while longer. Classification was happening in parallel with Southern Ireland seeking its independence from London. When the Irish Free State was founded, it did so when classification was finished, but before numbering had started. Until 1977 Ireland had T and L roads.

Enough letters: it was time to start pencilling in some numbers.

Crunching the numbers

Civil servants in London numbered only roads in England and Wales, with Scottish counterparts numbering their own roads shortly afterwards. A hub-and-spoke system, loosely modelled on the one used by France, was the intention from the outset. But exactly what form the system would take, and where the spokes would lie, was a problem.

One document lists the London radials and numbers them from one to five - missing out the London-Dover route and giving England and Wales just five zones. It's not clear whether this is just a mistake in an early draft, as there are references on the same page to six zones.

A paper titled “Suggested System of Route Numbering”, written by Col. Richmond himself in May 1921 (referring only to England and Wales) lists to the A6 as running to Glasgow, and states that "number 6 sector is bounded on the North by the Carlisle - Berwick-on-Tweed Road to which No. 7 is allotted". Had the A7 run along the England-Scotland border it would have split the system into two very clear parts, with zone 6 prevented from entering Scotland at all.

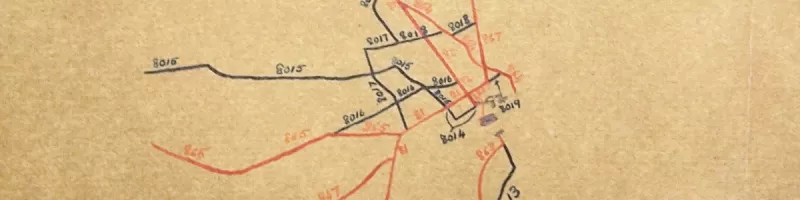

The process of allocating numbers within zones was even more intriguing. There appears to have been a system of letter codes indicating first and second class status, probably used to distinguish one from another while decisions were taken about which routes would take precedence where roads of the same class met. Often Class I roads in a given area were given a single letter and Class II roads a pair of letters.

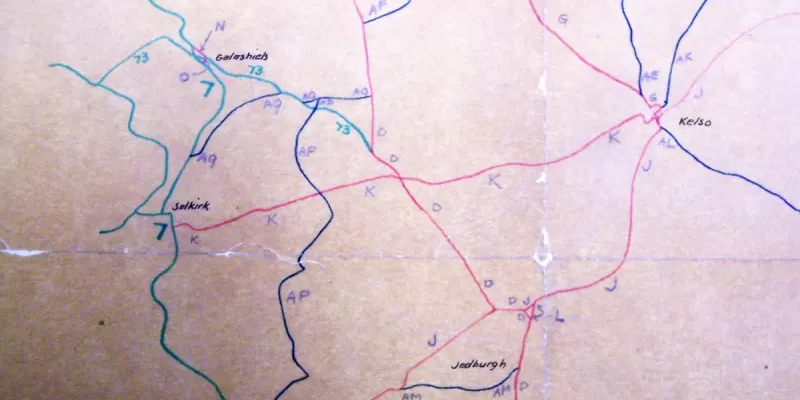

By August 1921, much of this initial work was nearing completion, and correspondence was being sent north for Scotland's highway engineers to begin considering their own scheme. There was still great uncertainty about what would happen north of, and even along, the border.

W.L. Campbell at the Roads Department in Edinburgh was instructed that "the routes you should number in Scotland are 7, 70, 71...79; 8, 80, 81...89, and 9, 90, 91, 92...99." The letter continued:

"There is an objection to route 6 terminating at Edinburgh. All roads in each English sector can be numbered with 3 numerals - the extension of Sector 1 into Scotland would necessitate some of the roads in the Scottish portion of zone 6 bearing four numerals.

"I, personally, see no objection to number 7 being given to the border road and the length Hawick to Edinburgh being 7a."

English numbering was now in progress, and Scottish numbers were about to be produced, but this was still a system in its infancy. It would not be long before engineers found that four-digit numbers were inevitable on both sides of the border and in every zone. But we came very close to having a bizarre "A7a", which would only exist to contrive a change of zone along the border.

The same letter went on to suggest that, north of the recommended route for A8, which was Leith to Gourock, there would probably be enough zone 8 numbers to dispense with zone 9 completely.

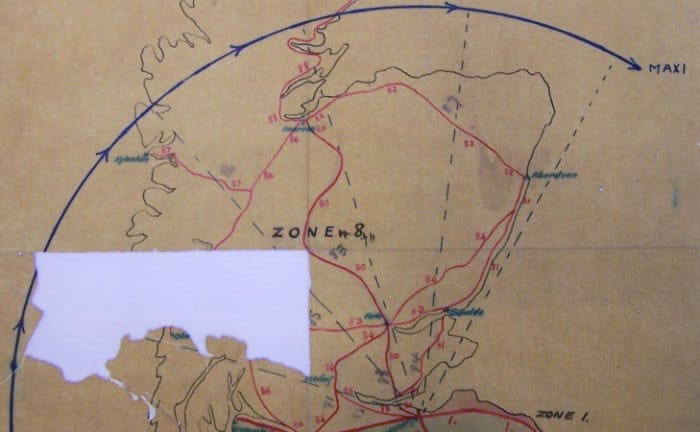

This was a serious proposal and diagrams were produced to demonstrate that it was viable. In this interesting scheme the rest of zone 8 was allocated as follows:

- A80 Edinburgh - Inverness via ferry across Forth estuary

- A81 Rosyth - Aberdeen via ferry across Tay and Dundee

- A82 Aberdeen - Inverness

- A83 Oban - Perth - Dundee

- A84 Glasgow - Perth - Stonehaven

- A85 Edinburgh - Stirling

- A86 Glasgow - Fort William - Inverness

- A87 Fort Augustus - Kyle of Lochalsh (for Skye)

- A88 Inverness - Thurso

It’s not clear why this considered. Possibly the engineers simply thought there was no need to use more numbers than necessary. It’s been suggested that, with Irish independence still a few months away and by no means certain, zone 9 was being reserved for Ireland. But that is highly unlikely because, even before independence, both Northern and Southern Ireland were operating as self-rule territories that would decide their own entirely separate numbers - which, of course, Northern Ireland eventually did.

Another possibility was that numbers beginning with 9 would be useful spares, with a stock of important-sounding two-digit numbers ready to be deployed anywhere in Great Britain when new roads opened.

All the same, documentary evidence is patchy, but in the end zone 9 was retained, and both Classification and the first round of numbering were finished by 1922. The first numbers, A1 to A99, were cleared to go on signs.

Going public

Map publishers had long known that road numbers were coming, and most of them were very eager to get hold of these exciting new codes that identified each link in the network. Bartholomew’s were so eager to get a head start on their competitors that they published a map with leaked information on the routes of A1 to A99. The company was left looking a little foolish when the final scheme was revealed with several noticeable differences the following year.

Michelin were keen too. When the first batch were released in July 1921 they were invited to send representatives to the Ministry to inspect the new scheme. In order that there would be no doubt whatsoever, no matter how minor the question, a series of obsessively large-scale maps were drawn up for the handful of places where the running of two route numbers concurrently could not be avoided.

There was also a great deal of interest from members of the public, and archive documents on the subject contain an incredible number of letters asking how road numbers were allocated or how the system worked. Each one got its own reply, individually written but always along the same lines.

In an attempt to better inform the public, the Ministry published a booklet called List of Class I and Class II Roads and Numbers on 1 April 1923. In parallel, the Ordnance Survey published a series of half-inch “Ministry of Transport Road Maps” which were specially annotated with all the new road numbers - today you can, incredibly, see almost all of them on SABRE Maps. But the public’s interest was not as great as hoped. Most copies of the booklet went unsold, and it was never updated; the maps, meanwhile, went through periodic revisions but never gained great popularity and were discontinued in the 1930s.

Out on the roads, local authorities were actively encouraged to put numbers on new signs, and to begin appending them to existing ones, as soon as the first batch of numbers were made public in summer 1921. The Ministry of Transport covered all such costs, and once the first 99 A-roads were done they were keen to see the signposting applied to progressively smaller and smaller routes.

It's just as well that it took a while to get the numbers out in public, because errors did creep in to the original system. In September 1924, the Ministry sent a letter to their Divisional Road Engineer in Yorkshire to ask whether any signs had yet been erected on the Hook Moor to Towton road east of Leeds - the reason being that, while it started on the A1 and headed east, placing it entirely in zone 1, it was originally numbered B6379.

There was a sigh of relief when the response dropped onto the Ministerial doormat, because the answer was no, and the number B1217 was applied without having to change any signs. In 1999 the closure of its connection to the A1 meant that it was extended west, into zone 6, and it is now again wrongly numbered, but the B6379 couldn't possibly make a return from its 75 years in exile because it now lies between Scholes and Low Moor elsewhere in the county.

T for trunk

A and B were settled, but before long the letter T was threatening to make a comeback. By the 1930s, long-distance motoring was becoming a reality and the Ministry of Transport was concerned that major long-distance routes were inconsistently maintained by County Councils. The Trunk Roads Act of 1936 would resolve this by giving the Ministry direct control of major roads.

The Act stipulated that the new Trunk Roads must be numbered for reference, and there was much head-scratching about what the numbers should be. In one draft plan, A-road numbers would be reorganised so each trunk route had the same A-number from start to finish. That idea would see the A62 and A63 replaced by a coast-to-coast A580 between Liverpool and Hull. This was abandoned in favour of new T-numbers, most of which would be produced by copying the number of the A-road that each Trunk Road used for the greatest length, such as the T30 from London to Penzance. However, a few wayward decisions were also taken - the T22 crossed northern England, bearing no relation to the A22.

For a while the Trunk Roads were going to be extremely conspicuous. A draft policy document stated:

"All posts on Trunk Roads carrying directional, mandatory or other signs to be painted red and white chequer instead of black and white as at present. This would ensure immediate recognition of any Trunk Road."

In addition, where T-numbers appeared on road signs a distinctive cartouche would be used: a giant T on a pale green background, which would also appear on marker posts placed by the wayside.

The reason to make these new numbers public was simply so that maintenance crews could be directed to work sites. For this reason alone it was expected that motorists between, for example, Birmingham and Birkenhead would have to get used to driving on the T42 instead of the A41.

T-roads never came to pass, thanks to a remarkable coincidence. In mid-1937 the Ministry became aware that the Ordnance Survey were providing a new way of locating points on their maps with the National Grid - so any point could be located to within a few yards by a string of coordinates.

It was discovered quite by accident. A senior cartographer at the Ordnance Survey was enlisted to write a leaflet explaining the new coordinate system, and sent his draft text to an old friend to get his comments on it. The old friend happened to be a senior Ministry of Transport civil servant working on Trunk Road numbering. He immediately realised that it would be possible to send work crews out with a map and a set of co-ordinates, which meant the Ministry could keep the whole messy business of Trunk Road numbers out of sight. T-numbers were created, but used in the end just for internal reference.

If it wasn't for a chance encounter between old friends, we might even today be driving on T-roads.

The history of motorway numbering

The story of how motorways came to be numbered is every bit as interesting, and slightly more panicked, than this one. The full story is over at our sister site Pathetic Motorways.

A century of change

In 1937 the T-road question was resolved by the Ministry’s dedicated Roads Classification Section, but road numbering would not stay novel or important enough to retain its own department for long. Over time it has been progressively demoted to a point where it sometimes feels like an afterthought.

The original 1920s system was, for a short while, maintained with extreme diligence. Through the rest of the twenties, annual revisions to road classifications were produced, with numbers being changed wherever traffic levels called for an amendment to a road’s class. A major revision was carried out in 1935, with several main roads being diverted in an attempt to improve long-distance navigation. But that was the last time road numbers would receive a complete review.

The strictest rules of the original system were progressively abandoned. New roads no longer had to receive the next number within their zone in strict sequence, and existing roads began to be diverted on to bypasses rather than staying doggedly on their original line. Concurrencies - what road enthusiasts often call multiplexes - where one road number is “carried” along another, reappearing later, began to be permitted. Pragmatism replaced purity.

There is some evidence that the Ministry’s own management of classification deteriorated over the decades. By the late twentieth century its card index of all road numbers was no longer accurate or useful, with many new numbers missing, old numbers out of date and itineraries incomplete. It is fair to say, at this stage, that SABRE holds a far more complete and accurate record of the UK’s road numbers than the modern Department for Transport or any other highway authority.

Then, the greatest change since 1935 happened in April 2012, when the Department for Transport handed responsibility for classification over to local authorities. Road numbering is now decentralised and devolved. No approval is needed if your local council wishes to make a new A-road or delete an existing B-road. They may do as they please.

On the face of it this sounds like a recipe for chaos, but the official guidance does place a responsibility on authorities to consult with each other when they want to make changes to a road that crosses a boundary. The DfT also states, as part of this policy, that it will maintain a central register of all road numbers (good luck!) and should be contacted to obtain an unused number when a new one is needed. However, they also admit that “the department recognises that neither local authorities nor central government will have comprehensive records of classification decisions taken before 2012”.

It remains to be seen whether the walls will come down on the road numbering system in light of this development, or whether the nine zones and other associated rules will survive in some form.

Most likely we will keep muddling through with a mix of good and bad decisions and a system of numbers that only grows more complex with time. When you’ve been numbering roads for a hundred years, it could hardly be any other way.

Picture credits

- Photograph of High Street, Broadway, is taken from an original by the Kenrick Family and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Classification form and sample itinerary are extracted from MT 38/18.

- Photograph of André Michelin is in the public domain.

- Diagram of Napoleon's Routes Impériales is in the public domain.

- Diagrams of numbering process, lettercodes and Scotland without zone 9 are extracted from MFQ 1/708.

- Diagram showing T22 at Brigg is extracted from MT 39/770.

- Image of front cover of 1923 road numbering booklet is from "1922 Road Lists", SABRE Wiki.

- Photograph of B-road sign in Somerset is taken from an original by JR and used with permission.

Sources

- Road Board instigates Classification, 1913; Classification process and forms, 1914: MT 38/18

- Classification restarted 1920; Michelin correspondence; Trunk and Link designations replaced with A and B; hubs and spokes modelled on France; early draft lists only five London radials; A7 along England-Scotland border; A7a suggested between Hawick and Edinburgh; no zone 9; Bartholomew publish map with leaked numbers; error in numbering B6379: MT 39/241; MFQ 1/708

- Maps to show concurrencies: MFQ 1/708

- Numbering booklet and OS maps published: "1922 Road Lists", SABRE Wiki

- Trunk Road numbering and signage recommendations: MT 39/770

- Concurrencies now permitted; DfT hands classification responsibility to local authorities: "Guidance on Road Classification and the Primary Route Network", Department for Transport, 13/03/12