The system of A- and B-roads we use today in mainland Great Britain is now more than a hundred years old. How does it work?

These days, travel around the world and you will find road numbers of some description in almost every nation. They are a staple of navigation, one of the basic expectations of a modern transport network. But the details vary from place to place: sometimes there are letter prefixes to distinguish different types of road, and sometimes stylised shields or other graphical devices. Some are laid out so the numbers form meaningful grids or trees or spokes, while others are scattered over the landscape at random.

Here in the UK, we settled on the letters A and B, and with them a whole list of rules about how to form numbers based on the importance and location of each road - rules that have persisted since 1921.

Classified details

Before we get on to numbers we need to begin with Classification. All-purpose roads in mainland Britain - that is, all public motorable roads, excluding motorways - are divided into three classes.

The first two types are referred to as classified roads, and highway authorities receive an annual maintenance grant from the Treasury proportionate to the classified roads they maintain.

- Class I roads are major through routes, forming the basic network of main roads. They qualify for a higher grant rate, and they get numbers prefixed with an A.

- Class II roads are less important, often of a lower physical standard, and serve smaller settlements or form connections between other roads. They get a lower grant rate and numbers prefixed with a B.

The third type of road is, logically enough, unclassified. These are the minor roads that are left over - country lanes and city streets. Unclassified roads don’t get public numbers. (This category actually has multiple variations, including “Classified unnumbered”, but we're not going to get bogged down in that here.)

So, we have a letter. Now we need some digits.

Hubs and spokes

The allocation of numbers is based on a hub-and-spoke system, with the country divided into nine zones that radiate from a central point. Because mainland Britain is long and narrow, and because things are always a bit different north of the border, there are actually two hubs, London and Edinburgh.

Radiating from these hubs are the nine principal A-roads. There have been a few changes since the 1920s, and today they can be broadly described like this:

- A1 London to Edinburgh

- A2 London to Dover

- A3 London to Portsmouth

- A4 London to Avonmouth

- A5 London to Holyhead

- A6 London to Carlisle

- A7 Edinburgh to Carlisle

- A8 Edinburgh to Greenock

- A9 Edinburgh to Scrabster*

These roads divide Great Britain into nine distinct zones. Each one takes its number from the A-road on its anticlockwise boundary - so, for example, zone 5 lies between the A5 and the A6. The exception to this rule is the boundary between zones 1 and 2, which is formed by the Thames Estuary and not the A2, in order to prevent a thin sliver of zone 1 being orphaned in the north of Kent. As a result the A2 doesn’t form a zone boundary.

All other A- and B-roads get their number from the zone they lie in, so a road in zone 5 will have a number that starts with a 5. Simple.

Of course, there are also rules to decide how the rest of the digits are assigned, and we'll come to that shortly. But there's a more pressing concern to examine first.

Crossing the line

In the real world, roads aren't as neat and tidy as you might hope. If you don't keep a close watch on them, they have a tendency to clear off in whichever direction takes their fancy, and just because you have declared that this is a certain zone and that is a different one, it won't stop roads from wandering away across the boundaries.

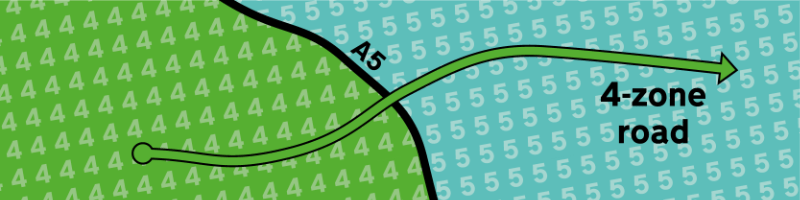

The zones count clockwise around their two hubs, and roads that cross boundaries also follow a clockwise rule. If a road crosses a zone boundary, it takes its first digit from the furthest anticlockwise zone it enters.

In this example, the road lies across two zones. It has a number starting with a 4 because zone 4 is at the furthest anticlockwise part of its route. It can proceed eastwards into zones 5, 6 and 1, but it can't go the other way into zone 3. If it did enter zone 3, it would need a zone 3 number.

The furthest anticlockwise zone doesn’t need to be at one end or the other. If you examine the route of the A41, you can see that both its ends are in zone 5, but in the middle it crosses the A5 to spend quite a lot of time in zone 4.

This clockwise rule means that you should find no zone 3 roads in zone 2, but you'll find plenty of them in zones 4 and 5. (The reality, though, is that you can find roads out of zone, simply because the rules haven’t always been followed.) Some roads really take advantage of the clockwise rule and clock up some serious mileage: one of the most adventurous travellers is the A38, which leaves its home zone by crossing the A4 in Bristol and proceeds through zones 4 and 5 to end in zone 6 at Mansfield (where, presumably, it has a well-deserved sit down).

Two’s company

Now we have a system for allocating the first digit of all road numbers, and for dealing with the many roads that will cross zone boundaries, we need to fill in all the other digits.

The system was intended to allocate shorter numbers to important roads and longer numbers to minor ones. A-roads can have one, two, three or four digits, while B-roads can only ever have three or four digits.

As a result, the next most important routes, after A1-A9, are the two-digit A-roads. Or, at least, they were: a hundred years of changes to the road network has messed things up an awful lot, not least the introduction of the motorway network, which leaves many short numbers allocated to roads long since bypassed or demoted. The A66 is still very important, for example, but the A32 is of little consequence today. The number of digits no longer has the significance it once did.

Nonetheless, our two-digit numbers are next in sequence. In each zone, the lowest two-digit numbers are used - where necessary - as further spokes radiating from the hub city, arranged in clockwise fashion. The remaining numbers are then used cross-country, with lower numbers nearer the hub and higher numbers further away.

Zone 1 illustrates this nicely, with A10-A13 radiating clockwise from London between A1 and A2, and A14-A19 progressively further north:

- A10 London to King's Lynn

- A11 London to Norwich

- A12 London to Great Yarmouth

- A13 London to Southend

- A14 Rugby to Felixstowe**

- A15 Yaxley (Peterborough) to Hull

- A16 Stamford to Grimsby

- A17 Newark to King's Lynn

- A18 Doncaster to Grimsby

- A19 Doncaster to Wide Open (Newcastle)

Three’s a crowd

Next in turn are three-digit numbers. Since we are now looking at the allocation of hundreds of numbers, which are likely to be much less easy to arrange in logical sequence, the rules for allocating a three-digit number are more fluid.

The same rule applies to both three-digit A-roads and to all B-roads, which is that numbers are allocated beginning at the hub and working outwards. As a result, A-roads in particular are often found in clusters, like the A650s which are all around Leeds and Bradford.

In zone 4, you can clearly see that A400-409 start in central and west London; A440-449 are in Worcestershire; and A480-489 are all found in western Wales.

Any observant driver will intuitively see when this convention is broken, even if they don’t know what the rules are. A403, for example, was once allocated to Western Avenue in West London, a perfect fit for the group A400-409. But a numbering change caused it to become vacant in the 1950s, and it was later recycled for the main road through the industrial areas of Avonmouth west of Bristol. The number 403 feels a bit out of place there.

Similarly the A130s are all found in Essex, except for A135 and A139 which have both ended up in Stockton-on-Tees, where its near neighbours are all in the 170s. They are, again, recycled numbers that were originally given to roads in Essex.

In allocating B-roads, little distinction was made between three- and four-digit numbers, and allocation started with the three-digit numbers close to the hub and worked outwards. Hence Central London is full of unsignposted streets with numbers like B105 and B406, and four-digit B-roads start to be seen a little way out of London. In Scotland, where the population (and road network) are often much more sparse, four-digit B-roads are noticeably rarer; in zone 8 there has never been a need for a B-road higher than B8087.

All fours

Four-digit A-road numbers work slightly differently. Back in the 1920s, the architects of the numbering system hoped they might not need them at all, but it soon became clear that 999 A-roads would not be enough: even in zones that didn’t exhaust the full set of three-digit numbers, there would be few spares to use in future.

There are, fittingly, four categories of four-digit A-road, none of which were allocated in the same way: these numbers really were an afterthought.

The first set are numbers used because there weren’t enough three-digit A-roads. They tended to be used for slightly less important A-roads as part of the original allocation. So you’ll see, in zone 5, that A5000 is in North London, but A5004 is in Buxton, because they were just scattered through the zone as required.

The second set were used when it became clear that Central London’s roads were getting busy with traffic very quickly, and (since initially road numbering was all about traffic levels and funding) lots of urban roads needed an upgrade to Class I status. That meant a whole slew of new four-digit numbers, all in close proximity. They span zones 1 to 4, since those four zones are present in Central London, but for consistency they all have 2 as the second digit. Hence Westminster and surrounding boroughs are full of numbers like A5202 (Pancras Road), A1210 (Mansell Street) and A4201 (Regent Street).

The third set are for new roads in the 1920s and 30s. For the first couple of decades after roads were first given numbers, there existed a convention that new roads - sometimes including even bypasses - were given the next available four-digit number in their zone. The same applied where B-roads were elevated to A-status: the next number in the queue was allocated regardless what it was.

As a result, the UK’s first entirely new inter-city road was the Wolverhampton-Birmingham New Road, opened in 1927, which became A4123 - a completely unremarkable number that failed to convey the new road’s significance, selected because it was the next unused number in its zone. It was followed by A4124, an upgrade of a former B-road to Class I status later the same year. This strict sequence rule was gradually abandoned because it was inflexible and in many cases adjusting an existing number was preferable for navigation purposes.

The fourth group is, loosely, everything else. Today, thanks to the fact that each zone still has vast numbers of unassigned four-digit A-road numbers, new road numbers are often hand-picked to sound or look memorable. There is no particular sequence or logic; instead a number is often chosen to reflect other nearby roads or a previous number for the same road.

When the M40 opened between Oxford and Birmingham, for example, the old A34 was renumbered to A3400 - a longer number, reflecting its lower status, but containing a less-than-subtle hint about its former designation. It’s the only number in the 3400s. Or take the new road opened in 2015 that links Switch Island, junction of M57 and M58, to Crosby and Formby. In a nod to the fact it opens up access to both those motorways, it was given the number A5758. There are barely any other 5-zone numbers above A5284, the last sequential one in that zone, but it doesn’t matter because its number is catchy and memorable.

Northern Ireland and elsewhere

So far we’ve only discussed the zonal system of A- and B-roads in Great Britain. We should also talk about the rest of the UK and its associated dependencies.

Northern Ireland is, obviously, not part of the British system of nine numbering zones. Classification work started in NI at the same time, and numbering happened almost in parallel, but with significant differences.

NI has Class I and II roads, of course, and allocates them A and B letter prefixes just the same. But it has no zonal system for allocating numbers, nor does it worry too much about the length of the number. Consequently it won’t take long to describe because the system is rather more informal - or, if you are the sort of person who likes to see a logical system for everything, it’s just plain chaotic. Look:

- NI’s A1 runs south towards Dublin.

- The A2 travels all around the coast, a bizarre route that nobody in their right mind would use from end to end.

- The A3, 4, 5 and 6 are the four other most important routes across the province. Other main roads then take numbers counting up to A55 in the original specification.

- There are then a scattering of other numbers, seemingly randomly chosen, for A-roads allocated over the following decades (A68, A76, A97), until in the late 20th century a series of new A-roads were created which, oddly, are all in the 500 series - A500 to A523 - but barely any other three digit numbers exist.

B-roads in Northern Ireland are also rather haphazard, though they do seem to have been allocated in groups that run county by county. They begin at B1 - because, why waste a good number? - and progress to B210; there is then a big gap before another group of B-roads in the 500 series, presumably because someone in Northern Ireland thought the 500s were cool.

You’ll see A- and B-roads in other places, too. The Isle of Man has them, as does Jersey; in both places there are quite a lot of numbers in a small area with indications of a system where main roads radiate clockwise around the principal town. Britain’s influence stretches wider, too, with echoes of a similar system in some Commonwealth African and Caribbean countries.

* The A9 is actually Grangemouth to Scrabster these days, but the zone boundary continues even where the A9 doesn’t, so Edinburgh is a fair approximation.

** Originally the A14 ran from Royston to Alconbury, a short link between the A10 and A1. Most of this route is now numbered A1198. The modern A14 was created in the early 1990s as a new cross-country route to the port of Felixstowe. It breaks the numbering rules as it starts in zone 5, but apart from this act of rebellion, it works nicely as part of the zone 1 sequence in this new location.

Picture credits

- Photograph of A403 at Hallen Marsh junction is taken from an original by Bill Boaden and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of A4123 Birmingham New Road is taken from an original by Steve Daniels and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Map of Belfast area is an extract from the Reader's Digest Book of the Road (1967), incorporating the Ordnance Survey four miles to the inch series.

Sources

- Classified I and II; hub and spoke system with nine zones: MT 39/241

- Rules about crossing zone boundaries, length of road number corresponding to importance, number of digits in B-road numbers, new roads to take next number in sequence: "Memorandum on Route Numbering", Ministry of Transport, 28/06/22

- Northern Ireland numbering principles: "Classification - Northern Ireland", SABRE Wiki