The start of work on the motorway network in the late 1950s created a whole new type of road and called for a whole new set of numbers.

In many ways this dealt the original numbering system a blow from which it never recovered. Since the new motorways often replaced the most important A-roads, the association between short numbers and important roads was broken: long lengths of the A5 were now a backwater with a grandiose number, for example. Indeed, the whole idea that A-class roads were the highest and best grade was lost.

At the earliest stages, there were discussions about using A-road numbers for motorways, though the only specific suggestion was that A50 should be used for what is now the M1. That would have been difficult in practice, so it didn't take long for separate numbers with the prefix "M" to be favoured.

This page looks at how motorway numbers are allocated, and later how those confusing A(M) numbers work. Brace yourself: even though there are only 56 distinct M-numbers in use across the whole UK, there are three separate systems for allocating them (well, of course there are), so we’ll need to discuss England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland separately.

England and Wales

The system for allocating A- and B-road numbers has many rules, but step back and it has a certain elegant logic too. The zones count clockwise around the country while numbers get higher as you travel away from the hub. It’s rather pleasing.

The rules for allocating motorway numbers in England and Wales are a little bit like that, except entirely without the elegance. Scotland is not included in this system because, by the late 1950s, Scotland was looking after its own trunk roads, thank you very much, and so Scottish motorways were none of the Ministry of Transport’s business. Heaven knows what this system would look like with Scotland included too.

The allocation of numbers works according to zones, divided up by single-digit motorways, so that much at least is familiar. With London as the hub, the motorways M1 to M4 radiate outwards, starting with the M1 parallel to the A1.

Hence the first four routes run:

- M1 London to Leeds

- M2 Medway Towns Bypass

- M3 London to Southampton

- M4 London to Pont Abraham

There are two further routes, dividing what would otherwise be an extraordinarily large zone 4 into smaller pieces:

- M5 Birmingham to Exeter

- M6 Rugby to Carlisle, via Birmingham

In what way are these last two radiating from London? It’s all about branching. The M5 runs south from the Midlands, but for numbering purposes we must take its start near Birmingham as being the London end of the road. It's all rather Biblical: in the beginning there was London; and London begat M1; and M1 begat M6; and M6 begat M5. Examine the diagram and you can see - in a twisted way - that M5 is clockwise of M4, and M6 is clockwise of M5.

Even accepting this topological contortion, we immediately have a problem, because few of the main routes continue far enough to be a complete zone boundary.

The M2 doesn't live up to its important-sounding number, covering only part of the distance from London to Dover, so - as with the A- and B-road system - the boundary between zones 1 and 2 is the Thames estuary, and the M2 has no numbering significance.

There are then two competing schools of thought about how the other blanks are filled in.

Two tribes

The original numbering scheme, approved in 1961, sees the zone 1/6 boundary veer east to Hull; the zone 2/3 boundary extend in a straight line south west from M3 junction 8 to somewhere around Plymouth, and everything west of the M5 and M6 in zone 5.

However, publicity sent out by the Department of Transport and its successors in the late 20th and early 21st century shows a different pattern, with the M1’s boundary continuing up the A1 to the Scottish border; the M3 forming a boundary all the way to Southampton; and the area of England west of the M5 and south of the M4 being part of zone 3.

How or when the system might have been revised is anyone’s guess, and indeed the later version may even be in error - but it is fair to say that in both systems the result is a pattern of zones that is pretty arcane.

Just like the A- and B-road system, any motorway starting within one of these zones takes the zone's number. Hence the London to Birmingham motorway in zone 4 is M40; the Bristol Spur is in zone 3 and therefore M32. Motorways that cross zone boundaries take their number from the furthest anticlockwise zone on their route, so the M25 has a zone 2 number even though it then finds its way through zones 3, 4 and 1.

There are no further rules about selecting the rest of the digits. In many places an opportunity was taken to match the number of a parallel A-road, but not always. Numbers don’t have to be lower near the hub, or appear in geographical groups, or be allocated in sequence, or anything else. They just have to have the right first digit.

A few motorways suggest that other ideas were sometimes at play: the M27 was once planned to get a series of spurs with the matching numbers M271, 272, 273 and so on, while in Leeds someone had a bit of fun with the motorway linking the M62 to the M1, and called it M621.

You may wonder what disastrous consequences come of having two competing sets of zones that don’t entirely match. But so few motorway numbers have been allocated since the 1960s (and so few exist in general) that, in practice, there's almost no effect.

In the north east of England, the area that may be either zone 1 or 6 has no M-numbers. In the south west of England, the area that may be either zone 2 or 3 has only the M271, which may not have been numbered by someone paying close attention to the zoning rules anyway, if they were more interested in making all the M27’s spurs match. And in the area that might be either zone 3 or 5, there is only the M49, which would be wrong no matter what and was clearly chosen by someone who didn’t give a stuff for your silly zoning rules.

If you’ve made it this far, you deserve a break. Let’s travel to Scotland.

Scotland

From chaos to simplicity: the Scottish motorway numbering system can be explained in three steps, which include the whole process of selecting a route and constructing the road. This is all you need to do:

- Identify a congested route that should be relieved by the construction of a new motorway.

- Build a motorway next to it.

- Give the motorway the same number as the old road.

The result is logic and clarity: the M8 replaces the A8; the M9 replaces the A9; the M80 replaces the A80. This system immediately answers the question about why there is no M7: it's because there has never been a need to replace the A7 with a motorway, and alongside the A7 is the only place the M7 could ever go.

There are two little dark clouds on our otherwise clear blue horizon. The first is that any motorway that replaces an A-road with a long number must also be doomed to carry a long number. Just ask the M876: it’s a vital link in Scotland's motorway network, but it parallels the A876, and therefore it has a ridiculous number even though M81 to M89 are all still available.

Slightly more problematic is what happens if you build a motorway on a whole new line rather than shadowing an A-road. Scotland’s simpler trunk road network didn’t call for routes like this, equivalent to England's M1 or M6, but there is one exception. The M73 is an eastern bypass for Glasgow that was built on a whole new route. It had to take its number from the A73, which lies some way away and performs a completely different function. But it's, you know, roughly parallel. So that's fine.

Northern Ireland

Before the Ministry of Transport settled on the headache-inducing zones for England and Wales, it briefly toyed with another idea: a tree-and-branch system, in which motorways took their first digit from the route they started on.

Such a system was found to be overstretched by the network planned for England, but it was a good fit for the one Northern Ireland was hoping to build in the 1960s. Their proposals would see a number of routes all radiating from Belfast, and some of those would have had a few branches and spurs. A tree-and-branch system was ideal.

Many of NI’s planned motorways were never built, but the ones that do exist all follow this original scheme.

- M1 and M2 strike out from Belfast.

- M3, M4, M7 and M8 were proposed as Belfast radials.

- M5 and M6 would split from the M2 as further main radials.

- M1 would have branches M11 and M12, while the M2 would have branches M22 and M23. M21 was reserved for a future airport motorway, which would branch off the M2.

At the time the system was proposed, NI’s government was often accused of favouring the province’s Unionist communities. If you have ever doubted that road numbering can tell you more about a place than just how it numbers its roads, then look no further than NI’s motorways, whose designations might contain some hints about the way their creators saw the Province.

Take a look at the M23. There was enormous pressure to build a motorway to the province’s second city, which is predominantly Nationalist. A motorway was duly planned, but not a main radial with a single digit number, even though M9 was available and it would be one of the longest routes. Instead it was classed as a spur of the M2. The same happened on the Dublin road: a motorway was proposed, and again one that would be longer than many single-digit main radials, but it was classed as a spur, M11. We don’t know why these decisions were taken, of course, and it’s possible to read in all sorts of things that may not be there. But they are rather striking choices.

Anyway, we are not here to talk politics. We’re here for road numbers, and we’ve yet to tackle the weirdest of them all.

A(M): the other kind of motorway

There is another type of motorway number and it's unlike anything used anywhere else in the world. Only in the UK do we have a designation that’s a hybrid of two other types, with a letter in brackets after the number. It is usually described as an "A-road with motorway restrictions". These roads are proper motorways - the restrictions are the same and the standard of engineering matches the best and worst of regular motorways - just without a motorway number.

They have been used for a range of conflicting reasons over the years, but their original purpose was rendered obsolete half a century ago.

In the late 1950s, plans were being produced for the Doncaster Bypass, and a decision was made to build it as a motorway. But it wasn’t going to form one of the new inter-city motorways like the M1 or M6: it would just be an isolated bypass for a section of the A1, and the original intention was for a motorway that held the number A1.

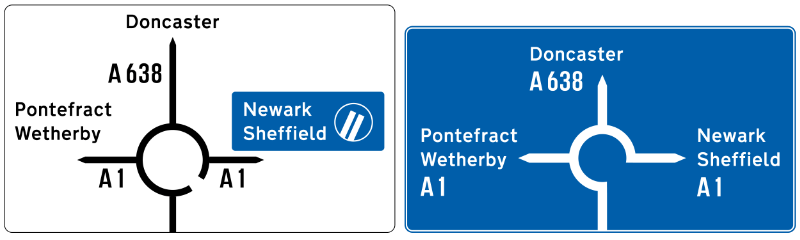

That was fine until December 1960, when the Anderson Committee published their recommendations for motorway signs. Early experiments for signs on ordinary roads approaching motorways had used colour coding, so the motorway arm of the junction was highlighted in blue. In a last-minute U-turn, the Committee abandoned that, and in the end all signs on all roads approaching any sort of motorway junction would be completely white-on-blue.

The unforeseen consequence was that, if the Doncaster Bypass was a motorway with the number A1, then the new signs gave motorists no indication which roads called A1 were motorways and which were just the ordinary A1.

It was too late to change the new system of signs, so the easiest fix was to add some extra text to indicate motorway status. How about an M for motorway?

In 1961 we gained our first two suffixed motorways, the A1(M) Doncaster Bypass and the A20(M) Maidstone Bypass, along with guidance that this new type of number was intended for motorway bypasses forming part of longer A-roads.

Then, in 1964, the Worboys Committee produced new designs for signs on non-motorway roads, sweeping away the strange decision to use all-blue on the approach to motorways, and removing the purpose of that extra text. And yet it made no difference: it was only needed for three years, but the (M) was here to stay.

Since that time it has found a range of different uses.

Jack of all trades

In their original guise, these numbers were supposed to be for short motorway bypasses of A-roads. Official guidance said that, when they were extended into a longer motorway, they should assume a full M-number. So the A20(M) ate its vegetables, grew up to be big and strong, and now goes by the name M20.

This hasn’t always gone to plan, though. The A74(M) was used for short sections of A74 that were upgraded to motorway in the 1990s, but no renumbering happened when the route was joined up, so half of the motorway from Glasgow to Carlisle is the M74 and the other half is arbitrarily A74(M). Meanwhile, in England, there are now multiple lengths of A1(M) - one almost 90 miles long - but even when joined up they can’t be given an M-number because the M1 already exists.

A(M) numbers then started to be used for short spurs of bigger motorways, in places where the spur and its parent motorway together formed a bypass for a section of A-road. Hence the A48(M) gets its number because it and its parent, the M4, could be described as bypass for part of the A48 between Cardiff and Newport.

Then there are A(M) numbers used as temporary placeholders, some more temporarily than others. The M23 was known, in the earliest stages of planning, as the A23(M), but it was given a “proper” number long before it opened to traffic. In more recent years, A446(M) was used to refer to what is now the M6 Toll during the extended period where a motorway was being planned and built but no public designation had been chosen.

The waters were further muddied in 2017, when Highways England (now National Highways) unveiled their “Expressway" concept, which would see dual carriageway trunk roads in England upgraded. An unexpected detail was that the highest standard Expressways would be given motorway status. In future, they said, an A(M) designation would indicate an Expressway, except in places those numbers were already in use, where it wouldn’t.

To demonstrate their enthusiasm, they announced the under-construction A14 between Alconbury and Cambridge would now be known as the A14(M). But the legal orders to make the road a motorway were never made, and the road opened in 2019 as plain A14. There have been no further attempts to redesignate any current or planned road with an A(M) number, and the concept appears to have been abandoned.

As a result, there are only so many A(M) roads in the UK - indeed, Wales and Northern Ireland only have one each. Thanks to their inconsistent use, obscure purpose and limited geographical spread, they are quite bewildering to a large proportion of motorists. The A1(M) is frequently and understandably confused with the M1, and doubt reigns about whether roads with these numbers are “proper” motorways and whether motorway rules apply to them. (They are and they do.)

On the other hand, we are rather stuck. There’s no simple way to discard them: you can’t convert them all to M-numbers, because many of the corresponding M-numbers already exist and refer to entirely separate roads. You also can’t convert them all to A-numbers, even though the original reason for sticking an (M) on the end is long since obsolete, because many of them branch off or run parallel to their matching A-road. We have painted ourselves into an awkwardly bracketed corner.

With Ax(M) designations we have what might be the most unusual road numbers in the world. But then, if you have made it to the end of an article about motorway numbering that’s as long as this one, that fact will probably not surprise you in the least.

Picture credits

- Photograph of M876 sign near Dennyloanhead is taken from an original by N Chadwick and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of A1(M) from Low Road footbridge is taken from an original by Jonathan Thacker and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of A74(M) at Elvanfoot is taken from an original by JThomas and used under this Creative Commons licence.

Sources

- 1960s version of zonal system; A(M) suffix added due to signage changes; A(M) bypasses replaced with M-numbers when joined: MT 112/67

- 1980s/90s version of zonal system: Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions information leaflet referenced at "The UK Road Numbering System", SABRE

- Scottish rules; NI tree system: "Classification", SABRE Wiki

- NI M21 reserved number: "N.IRL: M21 question resolved", Wesley Johnson via SABRE Forums, 21/01/09

- A23(M) as placeholder: "A23(M) Provisional Allocation", SABRE Wiki

- A446(M) as placeholder: "A446(M)", SABRE Wiki

- Expressways to take A(M) numbers: "Strategic Road Network Initial Report", Highways England, December 2017