For a while, the M5 ended at a 270-degree loop - but long after the motorway was extended past it, it kept on catching drivers unawares. In the end, it had to go. What did we learn from the Strensham Loop?

Imperfectly Odd is an ongoing series of blog posts about some of the strangest stories of UK roads past and present. In this post we're visiting Worcestershire, and a road junction that caused no end of headaches from its opening in 1962 to its eventual obliteration thirty years later.

It's also the explanation for the Imperfectly Odd logo. That odd loop-the-loop warning sign is the one that was used at Strensham, in one of many attempts to tame the junction's terrible accident record.

What's so odd about the Strensham Loop?

It doesn't exist any more, but when it did - from 1962 to 1992 - the loop formed the southbound exit from the M5 to the M50 at junction 8, Strensham Interchange. It was just a very sharply curved sliproad, really, but the lessons learned from it are now applied to sharp bends on roads across the whole UK. To understand what made it so important, we need to go back to the earliest days of the motorway programme.

The M50 opened in 1960, initially running from Twyning, north of Tewkesbury, to Ross-on-Wye, linking the A38 Birmingham-Bristol trunk road to the A40 towards South Wales. It was meant to connect industry in Wales and the West Midlands, promoting trade, a task considered so vital to post-war Britain that the M50 took top priority for construction. It was the fifth motorway in the UK to open.

Joining it in 1962, the first length of M5 started on the outskirts of Birmingham and ran to Strensham, the site of present day junction 8. It would one day be extended to Bristol, but until then the only way off at its southern end was onto the M50.

Linking the two motorways were sliproads, part of an interchange at Strensham that would one day connect with the next section of M5. Eastbound M50 traffic curved left and joined the M5 northbound. Southbound M5 traffic had a more convoluted journey: it curved left through 270 degrees, passing under itself, to join the M50 west. Both motorways, and the junction between them, were built to early standards that would soon be revised - but even compared to other roads of that era they were basic in their layout.

To say that the loop was a surprise to motorists would be an understatement. Unused to driving in motorway conditions, drivers found gentle curves for mile after mile, until suddenly the road veered left and careened around a sharp turn that was passable at only about 30mph in a car and less in a lorry. From the day the motorway opened, there were accidents.

Show me a sign

The M5 and M50 both had just two lanes each way in 1962, so the non-junction at Strensham should have seen both traffic lanes passing through uninterrupted. But on opening day not even that was right.

The road was laid out anticipating a future southward extension of the M5, of course, but work had yet to start on it. Still, for reasons best known to themselves, the designers of the road had painted some of the junction's road markings as though it was already there.

On a site visit in September 1964, two years after it opened, the Ministry's engineer Mr. Massey observed the completely misleading layout facing southbound drivers.

"Just before the bend the two lanes developed into three… Then at the start of the acute turn the nearside lane disappeared into the hard shoulder, leaving a potential three lanes of traffic to sort themselves into two at the very worst point of the bend. A similar set of markings were on the northbound carriageway."

There was also a series of warning signs on the approach, and at the point where the road veered left, a strange chequerboard sign with a pointed end was mounted on unusually high supports.

Massey observed that the warning signs already in place had "French Horn" symbols - a special loop-the-loop warning created specially for this location in spring 1963, at the request of the police. The combination of unusual road layout, unusual markings and unusual signs was not working. Even a word with a police patrol wasn't enough warning for some.

"The police quoted the recent case of a motorist being warned (just before leaving the nearby Service Area) of the hazardous bend and becoming a casualty there immediately afterwards."

He noted that vehicles on both bends tended to cut the corner, veering into the hard shoulder. The chequerboard sign was too high to catch headlights at night, and in the daytime the pattern actually made it blend in to the trees behind it. And on the northbound side, a large "services 1/2 mile" sign had been thoughtlessly erected on the inside of the corner, restricting forward visibility at the sharpest part of the turn.

Massey recommended replacing the chequers with the new black-and-white chevrons introduced by the Worboys report, painting "SLOW" on the road, removing the services sign, and fixing the road markings.

What he absolutely could not do, though, was add signs suggesting a speed for the corner. The Ministry of Transport refused to even consider them, because no signs showing advisory speeds were permitted in those days. Telling drivers how fast to take a corner was ridiculous, you see: every driver and every vehicle was different. A well-educated driver would select a safe speed for the conditions and for their vehicle.

No one speed could be right for everybody. The police agreed. The accidents continued to happen.

The magic number

It was summer 1965 when a crew was finally dispatched to Strensham Interchange to fix the signs and the road markings. Not long afterwards there was cause to think again.

Back in 1963, the Worboys Committee had recommended new signs indicating to drivers the severity of bends. Since then, the Road Research Laboratory had been looking into it, and in August 1965 they published their findings.

They examined signs from the USA and New Zealand, where bends were routinely marked with advisory speeds, before investigating home-grown ideas that suited the Ministry's dogged belief that signposting speeds for bends was a terrible idea.

Among the possibilities were a series of changes to the "bend" and "double bend" warning signs, with symbols variously showing gentle and sharp corners. Another was to use star ratings for bends - with one, two or three stars depending on the severity of the turn. The Strensham Loop would surely have been a three-star corner.

Probably the strangest idea was the installation of white poles by the roadside, on the outside of a bend, which would vary in height. The shortest pole would be at the beginning of the turn, with taller poles through to the apex, and then gradually shorter poles again until the road was straight. The same number of poles would be installed at every corner, so gentle turns would have them widely spaced and sharp turns would have a cluster all together. But the RRL found that bends of wildly different severity would look the same at night from certain angles, so that was a non-starter.

Later the same month, with the report in their hands, the Ministry relented, approving trials at about 30 sites nationwide for "maximum speed" advisory plates to be installed at dangerous bends. One was on the M5, where southbound traffic would now see an advisory speed of 30mph in addition to the French Horn symbol.

Around the horn

The new advisory speed signs remained in place for evaluation, and by the summer of 1968 the results were clear.

Before the changes were made, the top recorded speed around the loop was 45mph. With the advisory speed signs, that dropped to just 33mph, and the number of vehicles exceeding the safe speed of 30mph dropped from 81% to just 6% of all traffic.

The Ministry had been right, of course, that drivers should select a safe speed for a corner based on the conditions and the capability of their vehicle. We all do it every day. But at a place like Strensham, where accidents kept happening, drivers were obviously having trouble getting it right. It turned out that suggesting a safe speed, in a place where a safe speed was hard to judge, was helpful after all. Who'd have thought?

The French Horn signs continued to play their strange tune for another two years, until February 1970 when the next section of M5 opened to traffic, extending the motorway south to Tewkesbury. At that point all the signs were changed to suit the new junction, and the unique symbol was consigned to history.

The advisory speed limit of 30mph remained, though. Over the following years the concept of an advisory speed limit under a warning sign for a bend came to find acceptance with highway engineers.

In fact, many of the complex interchanges built and opened in the following decade, during the peak of Britain's motorway construction boom, feature advisory speed limits on their sliproads - a very plain indication that the thing the Ministry had once banned was now fully embraced.

An unexpected solution

The sharp turns at Strensham were no longer the accident blackspot they had been, but there was still a tendency for vehicles to overturn occasionally as drivers either failed to see or failed to follow the advice on the signs.

In the early 1980s, another attempt was made to improve the situation with a new paint job, reducing all four sliproads to a single lane with lots of white paint. The new arrangement led vehicles as gently around the corners as possible, removed the temptation for overtaking manoeuvres, and maximised forward visibility around the corners.

The changes made a huge difference, and almost completely fixed the junction's problems with overturning vehicles - but the Strensham Loop's days were numbered. The M5 between junctions 4 and 8 had been built in the early 1960s with just two lanes each way, something that was acknowledged to have been a mistake just a few years later. By the mid-80s the two-lane motorway was suffering chronic congestion, and work began to widen it.

Many of the junctions built in 1962 were replaced with new layouts, providing more capacity and eradicating sharp turns and narrow sliproads. Strensham Interchange was no exception. The loops and corners were a recognised hazard, and no amount of white paint would make them safe enough. Compounding the problem was the proximity of Strensham Services, which caused weaving problems as traffic jostled to enter and leave the M5 in a very short distance.

The solution - designed in the late 80s, and built in the early 1990s when widening works finally reached junction 8 - was to replace the trumpet interchange completely with a new roundabout under the M5. The M50 would terminate on the roundabout, and the sliproad from the southbound service area would reach down to meet it too. The northbound service area was relocated to an entirely new site further north.

Not everyone was convinced. The new layout replaced a free-flowing interchange with one that caused everyone joining and leaving the M50 to negotiate a roundabout - hardly an upgrade for a motorway-to-motorway connection. The history of Strensham Interchange and the reason for such a seemingly backwards move is a regular topic of debate for road enthusiasts. But there's no denying the fact that the new junction did, at least, eliminate something that had been causing trouble since 1962.

The Strensham Loop left behind two things. One is visible on aerial photographs of M5 junction 8, where the shape of the former junction with its looped sliproads is preserved in the boundaries of the woodland just east of the motorway. You can see that the loop was, incredibly, smaller in diameter than the roundabout that replaced it - no wonder people kept getting it wrong.

The other is that we now post advisory speed limits on bends where it's easy to misjudge the safe speed, an innovation that makes it easier to take a corner safely and confidently even if you're not intimately familiar with what lies ahead.

That's a formidable contribution to road safety, nationwide, and an impressive legacy considering that the loop was just one largely forgotten sliproad, and one that only existed for 30 years. It was, in every way, imperfectly odd.

Comments

As far as I'm aware, the M50 no longer has very much traffic with the reduction in industry in South Wales, and is a bit of an historic relic of the past. Still useful though !

Still the fastest way from the midlands to South Wales, just need a Little Chef services halfway along to add to the retro feel

Bend signs with a similar symbol to the three star sign exist on the A44 just outside Broadway.

BroadwaS? Yes, those signs still exist all over the place.

No, Broadway – or more specifically Fish Hill, as seen here https://goo.gl/maps/v5qVbZdaG8owcLjo9 . I think these non-standard signs are used because at this point you're already on a bend so there needs to be a sharper sign to indicate that the bend is about to get much worse.

(It's really confusing of the A44 to go through two villages in the same county which differ by only their final letter, and to be pretty twisty both times!)

Gregg- only just seen you reply, apologies. Yes, it's very inconsiderate of them- I bet a lot of post goes to the wrong places. - I see what you mean about the sign. Cheers.

Interesting article. I remember very well travelling on this loop as a child on the way to holidays at Weston, when traversing the bend our luggage all used to slide to the right - travelling too quickly maybe! This service road looks like it could be part of the original loop left in place? https://www.google.co.uk/maps/@52.0479944,-2.1342589,3a,37.5y,276.61h,8…

Here on the east side, around what is now woodland; https://www.google.co.uk/maps/@52.0472874,-2.133391,246m/data=!3m1!1e3

I think that's an abnormal load holding area, but the northern half (with yellow stripes) appears to be the temporary southbound off-slip that was used during construction of the roundabout. It isn't part of the loop, though, which was all to the south-east of that bit of road.

That's right, there was a tiny roundabout placed on the alignment of the old underbridge. Here's a photo: https://www.sabre-roads.org.uk/wiki/images/f/f9/M50_-_Junction_8_M5_-_C…

Looking at the picture of the lorry on its side it looks like that bend has whats known as an "adverse camber". Or is it a trick of the camera?

I was 5 when the Strensham loop was built and I remember my father's fascination with it. He called it "the dough hook". I was sad to watch an iconic motorway junction being replaced with a boring roundabout, and always look out for the remnant still showing its yellow slow down stripes.

Wasn't there an early plan to build a motorway linking the M50 with the M69? The M69 South - M6 North interchange has a similar bend, although nowhere near as tight.

There was such a plan, but it postdates this junction by several years. The loops here would certainly have been removed because they'd be in the way of any east to south links.

The layout they came up with (as seen on Pathetic Motorways here https://pathetic.org.uk/unbuilt/strensham_solihull_motorway/maps/I/sect… ) still has a fairly tight loop, but it goes west to south which is a much more minor traffic flow.

Thanks a lot for writing this article - I've been wanting to know more for a long time about what the M5/M50 junction was like prior to the early 90s when it was rebuilt as a roundabout. Do you know roughly when the lights along this stretch of the M5 were first installed (it was definitely after 1962 and before 1992)?

The lighting was installed, during a number of separate contracts in the early 1980's. It was intended to be a ''temporary safety measure'' to operate only for while carrying out the reconstruction works on the (then) 2-lane motorway. It kind of got left.

The current load bay was formed out of part of the temporary (small) roundabout that was installed to facilitate movements during the Widening and Junction works.... I have a picture somewhere and will try to find it.

If you look up "Strensham to Solihull" motorway you will find the original plan to link Junction 8 with (what are now) M40/M42

Is the overturned lorry photo actually at Strensham ? Its bend is to the right, whereas Strensham in both directions was to the left. The photo does not appear to be reversed.

Yes, it was taken on the eastbound to southbound sliproad during the 1970s. There are seemingly no pictures of accidents on the original southbound to westbound loop, so this is the closest match I could find.

I have found a couple of RTA on the SB to WB link - and will post when sorted.

I remember the concrete used on parts of the M5, in Somerset I think. Going south it always made me realise not long until the seaside!

As for the M50, wasn't it intended to replace the A40 beyond Ross?

There's nothing to suggest the M50 was ever going to extend any further west than Ross. It was intended to get from the M5 to the A40, from where the A40 itself was dualled.

Was the OG Strensham interchange the only time a trumpet was used as a temporary terminus for a Motorway?

Off the top of my head, the former western end of the A20(M) near Aylesford (now M20 junction 6), and the eastern end of the A4(M) at Huntercombe (now M4 junction 7) were originally built as half-trumpets, similar to Strensham. However in both cases, the joining traffic went round the loop, rather than the exiting traffic.

There's a slightly stranger contemporary example in southern Hungary at the M6/M60 interchange - at the moment, all traffic is routed through the very large loop, though land has been cleared to build direct right-turn sliproads in both directions.

Having passed up and down this Mway many times, I've always wondered at he strangeness of the Strensham interchange, and avoid that service station unless absolutely necessary. Now I know why it's all so weird there! Thanks for this information.

I have a definite memory of this bizarre 270-degree motorway bend from 1965 when we visited friends and relatives in England. I have never before or since seen a motorway transition like that, and finally found it documented!

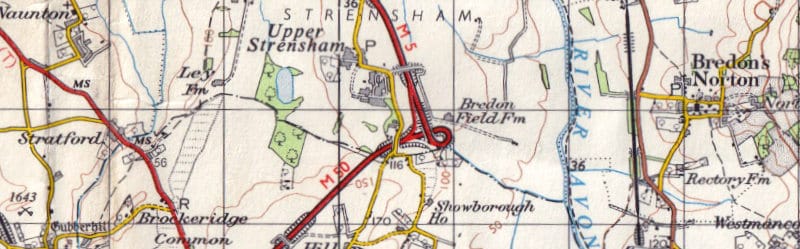

I noticed that on the OS map from 1962 the M5 and M50 are marked in red. Anyone know when OS went over to blue for motorways? As well as being interested in transport Im interested in cartography.

It was the introduction of Second Series 1:50,000 mapping in 1974 - see the SABRE Wiki.

Thanks for that.

By the way..I was the (then young) engineer who designed all those white paint markings ..before the widening and redesign

Add new comment

Sources

- MOT correspondence on warning signs at Strensham; RRL experiments in warning signs for severe bends: MT 112/159.

Picture credits

- Map of Strensham Interchange in 1962 is taken from Ordnance Survey One Inch sheet 143, 1953, revision A//*/*, revised 1962, on which Crown Copyright has expired.

- Aerial photograph of Strensham Loop is taken from "M5 Official Opening", 1962, published by Monk and now out of copyright; scan appears courtesy of LCC Municipal.

- Plan showing "French Horn" sign locations is extracted from MT 112/159.

- Archive photographs of overturned lorry, exit from M5 and works to re-mark the junction with single lane sliproads all appear courtesy of Paul T.

- Photograph of Strensham Interchange today is taken from an original by Philip Halling and used under this Creative Commons licence.

The very symbol of the series!