There were two reasons to be interested in variable message signs in the 1960s: traffic control and emergency warnings. While Bergo were attempting to find solutions for traffic control, the Ministry was actually more interested in finding ways that electronic signs could be used to make motorways safer.

Elsewhere in Europe, development work was already taking place on technology that would allow signs to display multiple messages. Not all of this was for road signs: Solari S.p.A were an Italian company who manufactured departure boards for airports and railway stations, of the type that use motorised flip-over panels to display their message and make a noisy clattering sound as the panels change over. Initially the Ministry of Transport approached them to see whether motorway signs could be made the same way, but this idea came to nothing.

A more promising idea came from another Italian firm, Sipra S.p.A, who sent technical drawings of a series of signs that had been supplied for use on Italian Autostrade in 1962 and were already in use. This unusual design had a large two-panel sign, the top panel being a window through which one of a number of slides were visible, and the bottom being a static sign that served to hide the slides that were not in use. Multiple sign faces were stored one behind the other, and motorised rollers could move the panels in and out of view, much like a window blind. When there were no messages to display the top panel contained a slide showing the distance to the next city.

Five emergency messages could be displayed — accident, fog, ice, road works and snow plough, all in Italian, English and German — and two flashing lights on the front of the sign were used to draw special attention to accidents and snow ploughs.

The Ministry of Transport's search for a way to warn drivers about motorway conditions up ahead had the potential to deliver a very lucrative contract for signal equipment, and one company, AEI, not only came up with an entirely new solution but also published lavish, glossy brochures titled "What's Ahead?" in order to sell the idea — perhaps a strange thing to do as there would only ever be one buyer in the market.

AEI's experience was in railway signalling and they adapted a system where a single circuit connected all the signs along a road, and mechanically tuned reeds in each sign would each respond to different sonic frequencies, enabling one pair of cables to send all manner of signals and instructions to signalling equipment along many miles of motorway.

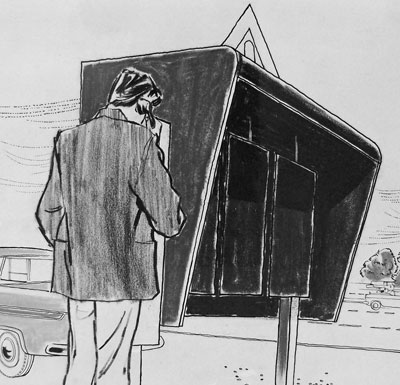

Their proposed signs were, however, much less clever. A large hooded box was proposed, with a warning triangle on top, and inside three panels on vertical spindles that could be rotated to present a blank face or a warning sign to traffic. The three warnings they proposed were letters: A for accident, I for ice, F for fog.

The design was meant to allow the signs to be used in remote areas where no power supply was available: the signs had no illumination and the motors were to be battery-driven. When it came to installing permanent signs for real a few years later, the Ministry of Transport got around this problem in a different way by just installing a power supply.

This system was not perfect, and was never tried out for real (though AEI had a hand in the communications system eventually developed for a permanent signalling system in the late 1960s), but AEI's engineers had at least spotted and avoided some problems that would come to plague systems that did get trialled on the roads. They suggested that the idea of manual control, meaning operation of the sign by a police officer parking his car and walking over to it, was not efficient and would not allow the sign to respond very quickly to changing conditions. They also recognised that maintaining accurate warnings about fog patches would be almost impossible. This is a problem we still have today.

Rotating panels had also been trialled in the USA in a different form, with a system of signs that had various legends printed onto the faces of rotating boxes, rather like a tombola drum with writing on the sides (shown left; click to enlarge). Multiple boxes, for different parts of the warning message, were contained within a metal cabinet with windows in the front — a heavy duty solution to the problem.

The device, produced by the United Sign Company in New Jersey, was widely used in the north-eastern United States, particularly on the New Jersey Turnpike. Their product line also included some very inelegant neon signs that made no attempt at all to hide their message when not in use, and which were fitted with a bell that would ring when one of its messages was illuminated.

The Ministry of Transport had brochures from this company, and many others, on their files, but in the end they decided to come up with their own design.

Accident, Skid Risk, Fog

Ultimately, the idea that gained traction was for signs with panels that could be illuminated to show a range of messages, in the belief that mechanical signs would not be "sufficiently reliable on so big a scale". The intention was that new signs might help during the winter when terrible accidents seemed almost guaranteed on a fog-bound motorway. A trial was to be run on part of the M5 in Worcestershire, where a system of remotely-operated signs would be installed every mile or two at the side of the motorway, linked to a central Police command post. They would be switched on to warn motorists of hazards further up the road.

Design work started in 1962, a time at which this sort of technology was still very expensive and when there wasn't very much experience with the best ways to communicate messages to fast-moving vehicles. The Ministry settled on the concept of written warnings to make the installation as economical as possible.

The method of control was a lot like AEI's proposal a couple of years before: to link the signs to a control centre, the Ministry rented spare wires in the telephone cables that had been laid down the verges of the M5 by the Post Office, who at that time maintained the emergency telephones. The original proposal had been to run the trial on the M1, which suffered from the worst fog-related accidents, but the telephone system on the M1 didn't have spare wires and the system on the M5 did.

Different sonic frequencies were transmitted down the telephone cables to trigger different signs. With a range of 18 frequencies available, a single pair of cables could control 15 signs, with 15 of the available frequencies used to identify the location of the sign to be activated, and the remaining three to select one of three messages. In this way any number of signs could be illuminated at any one time, but the control system only allowed one sign to be switched on or off at any given moment.

In February 1964, one experimental sign was installed on the northbound side of the M5, two miles north of what is now junction 6. It had three messages — Accident, Skid Risk and Fog — and was manually controlled. The word "Slow" would be illuminated at the top of the sign whenever any of the three messages was lit. Every letter of every word had its own lamp, with the letter cut out of a mask, and a lens in front of that.

This first trial was only meant to test how visible and legible the sign was in different light conditions, and the Ministry's press release warned that:

"To gain the maximum experience in the shortest time, the warning may appear even when no special hazard exists."

Some might say that electronic signs on motorways have been giving false alarms ever since.

In July 1964, work started on fitting out the remote control system using the GPO's telephone cables, and soon afterwards another 21 signs were installed at two-mile intervals on both sides of the M5, all remotely controlled from Hindlip Hall, the headquarters of Worcestershire County Police Force. Now a 35 km (22 mile) section of motorway was equipped with signs that could instantly be used to warn motorists of upcoming hazards, and the future had arrived on an unlikely section of motorway near Droitwich.

The trouble was that the trial was still in its early stages, the system was nowhere near ready to be rolled out nationwide, and the Ministry was about to come under enormous pressure to act more quickly.

Elsewhere on

Roads.org.uk...

Skid Risk, Accident, Fog 10 March 2025

For the first time, we can share pictures of the pioneering experiment that lit up the Worcestershire countryside with enormous signs 61 years ago.