Glasgow has long been Scotland's first city. With the colonisation of the New World, the city was well placed to serve as a port for shipping to the Americas and West Indies. By the 1700s Glasgow was a key trading centre and its heavy industry, shipbuilding and port activity continued into the modern age. In the 1930s Glasgow could claim to have built a quarter of all railway locomotives in the world.

By the middle of the twentieth century, Glasgow was beginning to suffer the sort of industrial decline that was affecting much of Britain. Growth in cheaper manufacturing overseas and a decline in shipping meant that the city was looking elsewhere for future prosperity. By the 1960s the City Council had a framework in place and was set to begin the transformation.

Large scale redevelopment

The future was a move away from industry and shipping, and a shift into service industries. If Glasgow was to survive it had to become more than just a modern city; it needed to become positively futuristic. The brave new world called for offices, commerce, communications and all the infrastructure that these things call upon.

There were few problems in the 1960s that could not be solved by massive capital investment in things that were made of concrete. So, the whole city was surveyed and divided into districts, each of which were assessed. Some passed the test and would be left intact. Many more - mostly inner-city, working class residential areas - were declared unfit and were to be renovated. They were given reference numbers to demonstrate the efficient, production-line regeneration that was planned. Glasgow called them CDAs - Comprehensive Development Areas.

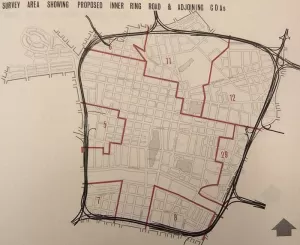

This was a useful mechanism for providing new infrastructure: if these areas were to be redeveloped, they could be carved up and disfigured without fear of the consequences to what was already there. It would all be replaced anyway. The new road infrastructure that was proposed was therefore designed using the CDAs as stepping-stones to avoid too much damage to the more desirable areas. The diagram above neatly illustrates how the Inner Ring Road was almost entirely within the boundaries of the CDAs surrounding the city centre.

Moving the people

A major part of the renovation was the almost obsessive destruction of the tenements. Many of Glasgow's poorest citizens had lived in cramped, substandard one-room accommodation for decades in areas like the Gorbals. In the 1960s, following a trip to Marseilles to see the new tower blocks being erected there by the famous architect Le Corbusier (such as the Unité d'Habitation, left), the council's policy was to demolish tenements across the city and re-house Glasgow's poorest residents in marvellous new tower blocks.

Even with the New Towns created at East Kilbride and Cumbernauld, the massive relocation of people happened mostly within Glasgow's city boundary, with the creation of districts like Easterhouse. Some cynics have claimed this was done to prevent the left-wing city council losing too many working class voters.

Either way, all of this was part of the one big plan: the renovation, effectively, of an entire city. Clearing out the tenements and re-homing their inhabitants in tower blocks freed up valuable space for new infrastructure. Areas like Springburn saw people stacked vertically to make way for the A803 Springburn Expressway which now slices the area in two.

A different approach

When the City of Glasgow appointed consultants to develop first its highway plans, and later its whole transportation strategy, the proposals they drew up were unlike any other plan produced in Britain. The reason was that they had followed American practice.

The whole concept of urban area renewal on such a scale was alien to the UK but had a precedent in the US, so when Scott & Wilson, Kirkpatrick & Partners were asked to consider the regeneration of Scotland's largest urban area they found that best practice had been established across the Atlantic. At least one expedition of representatives from Glasgow City Council and the consultants went and explored the extensive freeway networks on the east coast of America. They returned buzzing with ideas about a hierarchical structure of roads, elevated freeways and the wholesale regeneration of huge swathes of a city.

The resulting proposals were incredibly co-ordinated. Re-housing plans, for example, had new residential districts planned in connection with proposed new roads. Each phase of the plan dropped in to place with precise knowledge of how later schemes would tie in.

How this manifested itself on the ground is explored on the next page.

Picture credits

- Image of Unité d'Habitation taken from an original image by Rightee, used under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 licence.

With thanks to Fraser for information on this page.