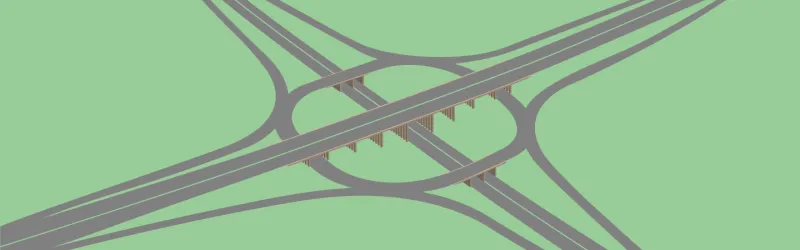

Cheaper than a row of run-down terraced houses in the path of a planned motorway, and about as cheerful, the three-level stacked roundabout (or "stackabout") is the blight of four-way junctions across the country.

Limited-access roads

Surface roads

Vertical levels

Bridges required

Access between roads

Number in UK

First built in UK

It's a junction that makes a statement, and the statement is "we didn't want to spend much money". As a result, these unfortunate interchanges have a reputation for causing chronic congestion and requiring expensive upgrade work.

They work best where a motorway crosses a fairly important A-road, but unfortunately many of them actually connect two motorways together, a job for which they don't usually have enough capacity.

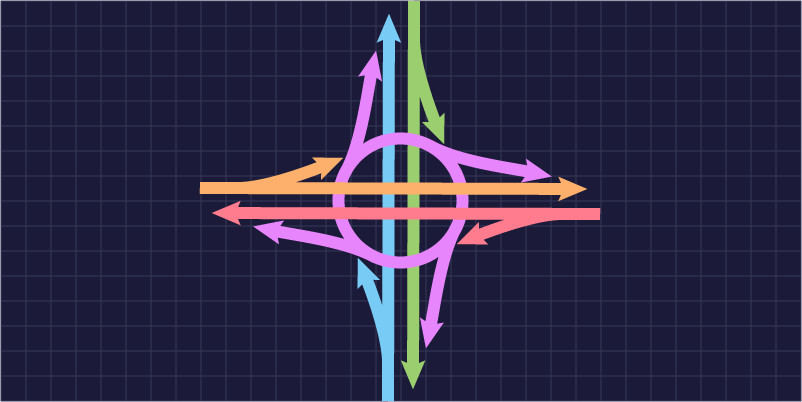

The stackabout is, of course, the bigger brother of the standard roundabout interchange — it's functionally the same except that there's a flyover to avoid the roundabout in two directions instead of one, so the roundabout is only handling traffic turning from one route to another.

Why build one?

The three-level stacked roundabout might actually be the motorway-to-motorway junction that is most numerous in the UK, so there must be something to commend it. And indeed there is. Compared to any other junction type, the stackabout is very small — and in the UK, where land is expensive and a major concern for any road scheme is minimising the amount of land it consumes, that's very important.

Another requirement of major junctions in the UK is that they need to accommodate other roads. In many places this type of junction was chosen because it means that a motorway-to-motorway junction can be combined with a junction for the local road network or a service area. The big roundabout can have lots of other entry points and accesses, meaning that this doesn't just have to be a four-arm junction, but instead could have any number of approaches. M4 J32 Coryton Interchange, north of Cardiff, is the most adventurous, with three local roads and a maintenance compound connected to its enormous roundabout, though strictly speaking it's no longer a true stackabout because a cut-through has been installed on the inside of the roundabout and one of the through routes has been signalised where it joins.

The Design Manual for Roads and Bridges actually recommends this junction type as the default for any connection between two motorway standard roads, and advises that a more elaborate, free-flowing interchange should only be built if traffic forecasts show that one of these would be unable to handle the traffic flows. That goes a long way to explaining its popularity: engineers are compelled to take this junction as their starting point, and have to make a very strong case if they want to build anything better.

The earliest example of a three-level stacked roundabout may be the Hendon Flyover, at the junction of the A406 North Circular Road with the A41. It was opened in 1965 and is positively tiny.

Advantages

- In comparison to any other four-way fully grade-separated junction, cheap and easy to build.

- Has minimal land-take outside the roads that are crossing.

- Easy to navigate and to correct navigational errors.

- Easy to upgrade capacity by adding traffic signals.

Disadvantages

- Large number of bridges and other structures.

- Three levels high, so can be visually intrusive.

- Low capacity — if both the major roads are motorways, the volume of interchanging traffic may be too high for a roundabout to handle.

- Apart from adding traffic lights, extremely difficult to upgrade. See M60 J18 Simister Interchange orM1 J42 Lofthouse Interchange for the type of struggle involved in increasing capacity.

- Excessively long name.

- Strange siren-like quality that causes otherwise level-headed planners to build them at major intersections.

Variations

Most of the variations on this type of junction are created through efforts to increase the capacity of the damned things.

The usual start point is to add traffic lights at every entry point. If (or, perhaps, when) this fails to fix the problem, the usual strategy is to add left-turn lanes bypassing the roundabout, so that the roundabout is then only handling right turns. The roundabout itself can also be widened, but this is expensive because it usually means widening or rebuilding bridges. The roundabout at M60 J18 Simster Interchange has now reached six lanes in width, which is double the width of any carriageway passing through.

A few desperate cases require more action. M1 J42 Lofthouse Interchange has had new sliproads tunneled underneath it at great expense and M25 J2 Darenth Interchange has had elevated sliproads added in two directions. In both cases these remove the heaviest traffic flows from the roundabout altogether.

The most exciting variant is at M6 J7 Great Barr, which is just mad.