The sun was shining on the morning of 5 December 1958 when Prime Minister Harold Macmillan took to the podium. He made a speech and put on what was, by all accounts, a very convincing Scottish accent to read some poetry by Robbie Burns:

I'm now arrived—thanks to the gods!—

Thro' pathways rough and muddy,

A certain sign that makin roads

Is no this people's study:

Altho' I'm not wi' Scripture cram'd,

I'm sure the Bible says

That heedless sinners shall be damn'd,

Unless they mend their ways.

The Preston Bypass, said Macmillan, was a sign that Britain was finally beginning the process of mending its ways, bringing them up to the standard that a modern country could be proud of. At this point, press releases promised the sight of him pushing a button which would automatically cut the ribbon and unveil the plaque, but unfortunately the system couldn't be made to work and so on the day there was no button and no ribbon. Instead, he simply had to reveal the granite plaque himself, and then get into the first car of the motorcade.

In doing so, he became the first person to travel by motorway, and also the first to break the brand new Motorway Code. The Ministry's new leaflet, distributed across Lancashire and available in shops elsewhere from the opening of the Bypass, clearly stated that "you must not walk on to the carriageways or cross them on foot", but Macmillan threw caution to the wind by getting out at two points on the Bypass to inspect the road. (One wonders if he truly appreciated the experimental wet mix layer in the road's sub-base or if he was just looking at the view.)

The Motorway Code, 1958

814.05 KB

The road he inspected was, in 1958, a revelation. From a new roundabout on the A6 at Bamber Bridge, laid out for a future continuation southward, a dual carriageway with a hawthorn hedge down the middle rolled over the Lancashire countryside, crossing the valleys at Walton Brook and Samlesbury on striking viaducts, slicing in and out of the Ribble Valley in majestic cuttings and finally coming to stop eight miles later at another roundabout near Broughton.

In the middle, the centrepiece was Samlesbury Interchange, with four looping sliproads running down to the A59 at the riverside. It was exciting stuff; so much so that coach trips were organised to that the people of Preston could see it.

There were concerns that the new motorway would cause motorists to lose their senses and start travelling at incredible speeds. Some less confident drivers actually avoided the road because they were scared of being overtaken by a line of sports cars doing warp 9 in the right hand lane. The police report into the first month of operation of "Motorway Six" actually revealed quite the opposite:

"Generally speaking, the standard of driving on the road has been good, the remarkable feature being the moderate speeds that vehicles are travelling. Our radar checks have only, on one occasion, found a driver going faster than 75 m.p.h., whilst most people drive at 40-50 m.p.h."

That month also saw the first motorway accidents, though both were single-car incidents with no serious injuries. The first happened on Sunday 7th December, two days after the opening of the road. An inexperienced driver stole a Ford Zephyr, lost control shortly after joining the motorway at Bamber Bridge, and went down the embankment, overturning the car in a field. The second was a fourteen-year-old who was so keen to see the new road that he took his father's Vauxhall Velox saloon out on Christmas Eve, joined the motorway at Broughton and got up to 70mph before losing control on the sharp bend, again dropping down the embankment and overturning the car in an adjacent field.

With vehicles travelling happily along at moderate speeds, things were going smoothly for the motorists. The same couldn't be said of the road itself. An unusually fast change in the weather caused the ground to thaw much more quickly than usual, and because water drained off the hard road surface into the hard shoulder - where it seeped into the base layers of the road and subsequently froze - the result was a motorway with patches of broken or crumbling surface. James Drake took the decision to close the motorway altogether to carry out repairs.

The papers were, of course, unimpressed. Just six weeks old and it had to close? How was this progress? But with no speed limit and no established way to carry out maintenance, it was thought safer to close the road altogether to allow work to proceed as fast as possible. Traffic was lighter in the winter anyway, and police reported that the old road through Preston was coping reasonably well during the closure.

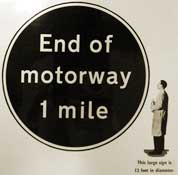

The final novelty was the new set of road signs. The Times reported that the signs were "a complete breakaway from present British usage" and that "some of them are 20ft. high". The signs initially erected on the motorway (like the one shown right; click to enlarge) were from an interim report produced by the Anderson Committee, which hoped to use them as a trial before making its final recommendations on the design of motorway signs. The very first ones were mounted on temporary scaffolding.

With the re-opening of the road in early 1959, the Preston Bypass was away and the motorway dream had become a reality. Already James Drake had turned his attention to construction work on the Lancaster Bypass and the Stretford-Eccles Bypass, both of them motorway projects on which work had started before the Preston Bypass was open. Further south, the first section of the M1 was less than a year from opening. The future of motoring was very bright indeed.

Picture credits

- Photographs of Broughton Lane Bridge and frost damage on the motorway are courtesy of the Motorway Archive Trust.

- Aerial photograph of Samlesbury Interchange appeared in the Manchester Guardian on 5 December 1958.