In the 1920s and 30s, miles and miles of new roads were built around the fringes of London in one of the biggest roadbuilding booms the UK has ever seen. They were designed to speed traffic around historic bottlenecks and open up new land for development, and even today the Arterial Roads built in that era form the backbone of the road network in many parts of the city.

Most of them are famous (and quite a few of them are downright notorious). Western Avenue, the Great West Road and the North Circular Road are well known to everyone. The A127 Southend Arterial Road actually has "Arterial Road" in its name. Others, like the Barnet Bypass or Sutton Bypass, might be less well known.

There are a few, however, that are almost completely forgotten — so much a part of the furniture that you might have to look closely to realise that they weren't always there, or perhaps so small and unexpected that you'd never think they were once part of a thrilling programme of new roads.

This feature takes a look around London and ignores the grand thoroughfares of the thirties to take a look at some of the more obscure creations of the pre-war era: London's forgotten Arterial Roads.

Greenford Road

If you're not local to north-west London you might never have heard of the A4127 Greenford Road. And why would you? It's a main road that travels north-south across suburbia, connecting Southall to Greenford and Sudbury. It meets the A40 Western Avenue at Greenford Roundabout.

For reasons that are not entirely obvious, it was built as part of the Arterial Roads Programme and opened in 1928 — meaning it pre-dates other more important roads like the eastern half of the North Circular and most of the Great Chertsey Road, and some maps even show it open while Western Avenue itself was still under construction. It runs for nearly four miles, so it was not a trivial piece of roadbuilding.

The actual Arterial Road runs from the A4020 Uxbridge Road to the A4005 Sudbury Hill. Today the A4127 extends both north and south from those points, but those extensions were later additions, created by reclassifying existing roads.

It's now largely built-up and looks like many other suburban main roads, but its width gives it away: not only is it reasonably wide, with broad pavements and a road surface capable of carrying four lanes of traffic (even if many parts are not marked out that way), it's precisely that wide all the way from Uxbridge Road to Sudbury Hill. Normal roads, that developed over time, rarely have a consistent width; new roads built from scratch are much more orderly.

The width of Greenford Road, from edge to edge including the pavements, is a perfect 60 feet (18.3m). It is also laid out, like many roads of its time, with long straight sections linked by occasional curves, and on a map it's clear that it is remarkably direct compared to other roads.

Near Greenford, it passes over the top of the Grand Union Canal. The bridge is number 15A, which means the road definitely wasn't there when the canal was built. From above there is a concrete parapet with minimal detailing; from below it's actually rather handsome. The faces of the bridge have arches, but if you look behind them, all the other bridge beams are horizontal and the whole thing is made of concrete. The arches are just decorative and this bridge isn't as old as it looks.

Where the Central Line crosses the road, the arched viaduct is actually even newer than Greenford Road itself: the tube didn't start running here until 1947. Behind it is another, lower railway bridge carrying an ordinary railway line. Both bridges clear Greenford Road in one single span of precisely 60 feet.

It might now be built up and not as fast as it used to be — you can bet that very little of it had a 30mph limit when it first opened — but Greenford Road is still the fastest route north and south in these parts, and still does what one suspects it was meant to do: connect suburbs in the vicinity of Harrow and Southall to the thrilling Western Avenue.

Bridgewater Road

Not far away from Greenford Road is the A4005 Bridgewater Road (though its southern section also goes by the names Ealing Road and Hanger Lane). It connects the A404 at Sudbury Town with the A40 Western Avenue, but you might know it as "the road at Hanger Lane Gyratory that isn't the A40 or A406". It appears to have been designed to divert traffic off the A404, allowing the new Western Avenue to function as a bypass for the Harrow Road from here into central London. Its opening date is difficult to pinpoint, but it was certainly open to traffic by 1928. It was probably built at the same time as Western Avenue itself.

Its start point is at a huge circular roundabout on the A404, a junction that could afford to be so spacious because the terminus of the new road was almost in open country when it was built. From there the road is marked for four lanes of traffic, with broad verges and parallel footpaths on both sides. Houses are set back on service roads. This is living!

The part called Bridgewater Road really is new, and runs parallel to the Piccadilly Line to bypass Wembley town centre. From Alperton to Hanger Lane Gyratory, existing roads were widened and straightened to the same standard as the new section to continue the smooth ride all the way to Western Avenue.

At Vicar's Bridge, the road crosses the River Brent, a mucky brown watercourse in a concrete channel. The bridge, despite being made of poured concrete, is more handsome than required for a road lined by pre-war semis and retail parks: it has balustrades that would be more at home in the gardens of a country house.

The width of the road, from boundary to boundary, is a generous 80 feet (24m) for its entire length. In places this is marked with two lanes each way with refuges and turning lanes, and in others three. Towards the northern end, Brent Borough Council maintain a short stretch with four lanes and a devil-may-care 40mph limit.

At the southern end this generous width is, instead, marked out for one lane northbound and three southbound on the approach to the terminal junction. That sort of flexibility is often missing on main roads in cities, but on a purpose built Arterial Road there's plenty of space to play with.

Hampton Court Way

1933 was a good year for bridges in London. Three opened all at once, two at new sites and one to replace an existing bridge. The two new crossings were Chiswick and Twickenham, both for the Great Chertsey Road; the replacement was at Hampton Court. Edward, Prince of Wales, opened them at a joint ceremony in July 1933.

The bridge he opened at Hampton Court is a handsome arched structure, designed by Lutyens, with carved stonework detailing and fine decorative lamps. It was intended to fit its historic surroundings: the stone and brickwork, and its ornamental detailing, are designed to complement Hampton Court Palace which is just next door.

If you look closely at the picture, a brick folly with three arches is visible immediately adjacent to it: the abutment of the original bridge, now a viewing platform. The new bridge is not just to one side of the original, but also at an angle to it.

This means that Bridge Street in Molesey is now a quiet shopping street and no longer leads over the Thames. It also means that the new bridge leads directly onto a road that didn't exist before: the A309 Hampton Court Way.

Leaving the bridge behind, Hampton Court Way strikes south, wide and straight, over another bridge for the River Mole. This one's not as elaborate but it has some similar detailing to the first and belies the fact that Hampton Court Bridge and this road were built as part of one grand plan.

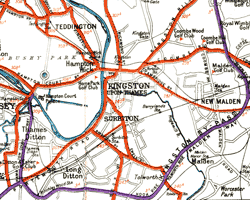

Hampton Court Way is, in fact, the completion of the Kingston Bypass. It opened just six years after the Kingston Bypass itself and travels in an almost straight line from the bridge to the Scilly Isles roundabout to meet it. Together with its older brother, it forms a three-quarter circuit of Kingston, intercepting all the main approach roads and removing all through traffic from the town.

The road itself should be familiar enough by now: broad, straight, with grass verges and footpaths on either side. Its width is not just consistent but also one of those nice, round numbers that inter-war roadbuilders liked so much: 80 feet (24m), just like Bridgewater Road.

Spur Road, Isleworth

There is more than one Spur Road. One is, by comparison to this, reasonably well known: Spur Road in Orpington is a spur from the Orpington Bypass, now part of the A232. This Spur Road is even more obscure.

Opened in 1925, the Great West Road is one of London's earliest Arterial Roads and, indeed, one of the oldest bypass roads anywhere in the country. But its builders laid a second Arterial Road as part of the same project: Spur Road in Isleworth, now part of the B454, forming a short link from their bypass back to London Road.

Only half that distance was actually built for Spur Road. Connecting to the A4 Great West Road is Syon Lane, an existing road that was borrowed to get traffic over the railway. South of the railway bridge, a new road was built — Spur Road — running 330m (0.2 miles) to reach the A315 London Road. It's not just the shortest Arterial Road in this list; at only 40 feet (12m) wide it's also the narrowest.

The reason it exists is because, at its southern end, it leads directly into the A310 Twickenham Road. Back in 1925, that was the main road towards London from Twickenham and other parts of Surrey. Without a connecting spur to the new Great West Road, all that traffic would continue to travel the old road through Brentford.

As well as the shortest and narrowest Arterial Road here, it may also be the most disposable. In 1933 the Great Chertsey Road was opened, forming a direct route from Twickenham and Richmond to London, and after just eight years' service Spur Road was no longer the main road to anywhere.

Charter Way

Today this route is little more than a sliproad off the A406 North Circular Road. Nobody is even sure what its classification is. The Ordnance Survey marks it, strangely, as part of the A1; Openstreetmap consider it a part of the A598. Either way, it is (today, at least) a single corner of the junction of the North Circular and Regent's Park Road in Finchley, a place better known as Henlys Corner.

Running for just a couple of hundred metres, and effectively one-way, it provides an exit from the eastbound A406 towards the A598 and is separated from the rest of the junction by Charter Green, a pleasant patch of open space. But don't be fooled by its diminutive appearance: it was once wider and more important. It was, in fact, the eastern terminus of the North Circular Road.

The first phase of the North Circular ran from Stonebridge Park, near Wembley, to this point, and no further. At its eastern end, it curved north to merge with Regent's Park Road, and that curve is Charter Way. The original plan had been for the North Circular to use a section of Regent's Park Road northwards from here before branching off to the east, which is why it ended like this. A few years later, when the North Circular was extended onwards, it was taken directly east on a new line instead, and this little stub was left behind.

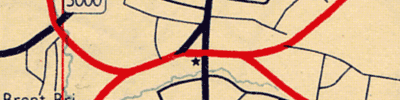

You might think that the story would end there, but because Charter Way was built as part of the Arterial Roads programme, it held a strange fascination for cartographers for decades afterwards. Even though it had become just a road between two arms of a junction, fronted by some 1930s flats and a synagogue, it continued to be specially marked on road maps of London as an "Arterial or Bypass Road" long after it should have faded to obscurity.

At its northern end, where it meets Regent's Park Road, is a bronze statue (locally known as the "Naked Lady", but officially called "La Délivrance") commemorating the victory of France and her allies in the First World War. It's a copy of a French memorial that was commissioned by Viscount Rothermere, proprietor of the Daily Mail, in 1927. His chose its location because he passed it frequently when visiting his mother.

Whether the Viscount passed through on the brand new Arterial Road that terminated here isn't clear, but certainly when this statue was erected, it stood at the end of one of London's great new highways.

The statue also gives away Charter Way's former width. It stands in a small flowerbed that has been designed as a traffic island, but it's no longer in the middle of the pavement. Charter Way has been made narrower, and the Green slightly larger, but the statue's garden fence still marks the original boundary of the road, making it possible to measure its original width. Just like the other Arterial Roads, it was a round number: 70 feet (21m), good enough for three lanes of traffic.

It might not be much of a ride today, but if you get a chance, turn left at Henlys Corner and take a trip on Charter Way — one of London's forgotten Arterial Roads.

Picture credits

Extracts from the following maps appear in this article:

- Geographia Two-Sided Road Map of London and SE Coast backed by 12 Miles Round London (undated, but from various incomplete Arterial Roads is circa 1928)

- Geographia "Up-to-date Road Map of Kent" (undated, but the Great Chertsey Road is shown so it is post-1933)

- Daily Mail Motor Road Map of South East England and Motor Road Map of London and 10 Miles Around (1946)

- Esso Road Map No. 1 London (undated, but shows the Barnet Bypass as A555 so it is pre-1954)

- Dunlop "Motoring About London" 3rd Extended Edition (undated, but shows the M4 Brentford Viaduct so is post-1965)