One of the oldest ideas in the urban motorway plan, and one of the lowest priorities, Parkway E would have been a brand new motorway from Central London to the south.

The roots of this project date back to the very early 20th century, and an idea to link Central London to the Crystal Palace, then an enormously popular visitor attraction. Over time it became a major road proposal, and then in 1944 Sir Patrick Abercrombie, author of the Greater London Plan, turned it into Parkway E, a new high speed road from Waterloo to the south coast, calling at Crystal Palace Park on the way.

By the time London's motorways were being planned in the 1960s, the Greater London Council found a void in the pattern of radial routes striking out in all directions. South London's sparse network of major roads offered no way in or out of London between the M23 and A20, but Abercrombie's Parkway was in just the right place to plug the gap. Better still, its route had been protected since the late 1940s, so development controls existed and in many places land for it was sitting vacant.

This motorway version of Parkway E would have run from Ringway 1 near Brixton all the way to open countryside near New Addington, where it would end on Ringway 3. As an entirely new route it was less urgently needed than improvements to London's existing overloaded main roads, which meant that, of all the roads in the GLC's Primary Road Network, Parkway E was ranked last for construction.

In the end, its extremely distant opening date, and the fairly vague reasons for it to exist at all, made it an easy project to drop from the deeply unpopular roads programme.

Previous versions of this page used the placeholder name "South Cross Route to Parkway D Radial", or "SCRPDR", for this road. That name was never its official title and is no longer used here.

Outline itinerary

R1 South Cross Route

Possible interchange with M23 (Tulse Hill Interchange)

Local connections to West Norwood and Crystal Palace

R2 Southern Section (Elmer's End Interchange)

Local connections to Elmer's End and West Wickham

R3 Southern Section

Cost summary

| Property acquisition (1970) | £15,500,000 |

| Rehousing (1970) | £3,500,000 |

| Construction (1970) | £58,350,000 |

| Environmental works (1970) | £2,415,000 |

| Total cost at 1970 prices | £79,765,000 |

| Estimated equivalent at 2014 prices Based on RPI and property price inflation |

£660,588,814 |

See the full costs of all Ringways schemes on the Cost Estimates page.

Route map

Scroll this map to see the whole route

Scroll this map vertically to see the whole route

Route description

This description begins at the northern end of the route and travels south.

Brixton to Addington

Parkway E would begin on the Ringway 1 South Cross Route at Loughborough Junction station, where a large free-flowing junction was designed in 1965. Travelling south along the west side of the railway line, it would obliterate Shakespeare Road and much of Loughborough Park.

The motorway would then run on a viaduct through Herne Hill, destroying the southern end of Railton Road, much of Herne Hill's shopping district and the eastern corner of Brockwell Park. It would run above the A215 Norwood Road and the adjacent shops, following the curve of the railway tracks around the edge of the park. Further along, the handsome Victorian terraces on the east side of Norwood Road would be demolished to make way for the viaduct.

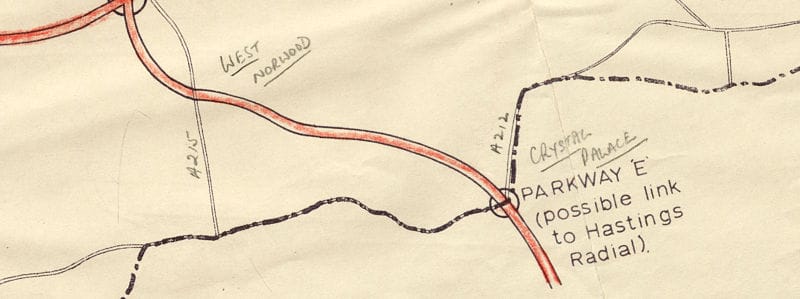

At Tulse Hill, the motorway would fly over the commercial district before turning south, joining the west side of the railway towards Crystal Palace and entering a deep cutting. Vacant land existed here in the 1960s. At West Norwood, the motorway would pass beneath the A215 Knights Hill and claim the whole of Cotswold Street before rising onto a viaduct again, passing over the industrial area at East Place. A corridor of land for Parkway E from here to Kingswood Primary School was protected from development and is still vacant today.

Dipping below Gipsy Road, the motorway would run through the northern edge of Norwood Park. A deep cutting or a tunnel would carry the motorway under the ridge at Crystal Palace itself, emerging on Anerley Hill, where a new line would be cleared through the houses on Cintra Park, Playdell Avenue, Waldegrave Road and Hamlet Road. Crossing the railway, the motorway would then curve around the playing fields before breaking through the houses on Wheathill Road and Cambridge Road.

A major interchange with Ringway 2's Southern Section would be located here, before Parkway E would turn south east across the cemetery and sewage works, skirting the houses on Long Lane, The Glade and Ash Tree Way. Houses on the south side of Aylesford Avenue would be demolished to smooth the curve to another vacant corridor at Monks Orchard, now occupied by Burrell Close.

Emerging into open ground, the motorway would turn south, brushing up against the Royal Bethlem Hospital and crossing Monks Orchard Road to reach the A232 Wickham Road. From here another protected corridor exists today between Oak Avenue and Bolderwood Way, preserved as woodland, on the boundary of the boroughs of Croydon and Bromley. Parkway E would follow this line south to reach open countryside at Addington Village, where it would turn south east to meet Ringway 3's Southern Section.

The parkway to the Palace

Nowhere are South London's roads worse equipped for fast and easy travel than in the wedge of suburbia from Southwark and Lambeth out towards Norwood and Croydon. That seems obvious now, but it was also obvious in 1905 - at least to one man.

William Rees Jeffreys was among the earliest people to understand and advocate for the world of the motor car. He was the first head of the Road Board, predecessor to the Ministry of Transport, and today a charitable fund exists in his name. Among his gifts were the paving of large parts of the British road network and the instigation of road numbering.

In 1905, a Royal Commission was examining traffic flow in London, and Rees Jeffreys had plenty of ideas for them. One of them, entirely new, was a grand avenue to approach the Crystal Palace, which had then only relatively recently been moved to its new permanent home atop Sydenham Hill. His sketches were remarkable, suggesting a wide new avenue in a ruler straight line from Waterloo Bridge to the Palace, brushing aside whatever buildings or geography may lie in its path.

Several of Rees Jeffreys' ideas were ahead of their time, not least his "grand boulevard" encircling the whole of London - a forerunner to the many ring roads proposed in the decades that followed. This was another.

The Crystal Palace itself burned down in 1936, but Jeffreys' new road still had its uses. It reappeared in Bressey's 1937 Highway Development Plan, reborn as an elevated road from Blackfriars to Camberwell and then a "New South Eastern Outlet" to the countryside beyond Beckenham. It returned in Abercrombie's 1944 Greater London Plan as a fast road with landscaped surroundings, running from Waterloo to Crystal Palace, Addington, and eventually the south coast near Hastings. Abercrombie called it Parkway E.

The Parkways in Abercrombie's plan were an ambitious hybrid of motorway and recreational parkland.

It is possible to give certain roads such a treatment that they partake of a park as well as highway character.

The dividing line between a normal road, which may be planted with trees, and a Motor Parkway is a matter of degree. …when a new parkway is being created it is a wrong conception to add a regular margin of green to the carriageways; the shape of fields, groups of trees, water courses or any other existing feature should help determine its boundary.

The vision for Parkway E was a landscaped road that would form part of London's system of parks and open spaces, while catering for the "colossal weekend traffic to the coast". It would open a corridor of interesting semi-rural greenery almost all the way to Elephant and Castle.

More speed, less Hastings

As with many of Abercrombie's grandest ideas, little progress was made on Parkway E when the war ended and rebuilding began. The Borough of Croydon was keen on it, and safeguarded its line from development by 1948. But the road ran along the borders of the Borough, so that only covered fragments of its route. Elsewhere not even that was done.

The idea was almost forgotten until the London County Council began tentatively sketching an urban motorway network for Inner London. Their early drafts included a handful of radiating arteries - including one called the "Hastings Radial". It struck out from the box of motorways surrounding Central London, passing through Tulse Hill and Crystal Palace on its way south. Parkway E was back in fashion.

Many of the LCC's plans were heavily amended as time went on, and when control passed to the Greater London Council in 1965, they were aligned more closely with the Ministry of Transport's ideas for the national motorway network. The LCC's "Norwich Radial" moved east and became the M11, while the "Basingstoke Radial" was abandoned in favour of the M3. But in the south, the GLC had a problem.

The Ministry didn't want a motorway to Hastings. They would provide the A20-M20 route into Kent, and the M23 south to Crawley. So those were in the plan. Between the two, though, no other major radial was intended.

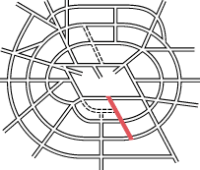

The issue was that the GLC approached planning as a science. They had worked out how dense their web of motorways needed to be to serve the whole metropolis evenly: between Ringways 1 and 2 the radial routes needed to be about four miles apart, but the lack of a motorway approaching London between the A20 and M23 meant a gap of about eight miles.

Their solution was to keep Parkway E in the plan, and simply abandon expectations that it would continue beyond London to Hastings. It was now a motorway reaching from Ringway 1 to Ringway 3, providing a new way in and out of the city for a part of London that otherwise would have none, and uniquely in the Ringways plan, it would be a radial route that only existed inside London.

The last in line

Because it didn't connect to any major road approaching London, there was no established flow of traffic to relieve, so there was much less urgency to build Parkway E than the other radial motorways. The GLC marked it as a project for "Phase 3" of their Primary Road Network, which meant work would start after 1991 - but it was also the lowest ranked of the Phase 3 proposals, so the bulldozers were unlikely to move in until much later still.

As a result, few detailed plans were ever made for Parkway E; it was just too far in the future for that to be worthwhile. Engineering drawings do exist for the section between Loughborough Junction and Tulse Hill, made in 1964, at a time when it would have met the Balham Loop, but the shape of the network changed a few years later without revised plans being made. The rest of the motorway's line was mapped for safeguarding purposes, so at the very least its route is known with some accuracy.

But everything else remained undecided, including Parkway E's possible link to the M23. Some outline plans of the Primary Road Network presented to the Greater London Development Plan Inquiry in 1970 suggest a post-1991 extension of the M23 north from Streatham Vale to reach Parkway E at Tulse Hill; it's even possible that the M23 would have taken over the northern end of Parkway E to reach Ringway 1. But there's no detail on that, and confusingly it's missing from other contemporary plans.

At the GLDP Inquiry, the panel didn't warm to Parkway E, and seemed not to share the GLC's view that a motorway was needed to fill the gap between the A20 and M23. The London Borough of Lambeth was also strongly against it. Their representative at the inquiry explained.

I have looked in vain for evidence that a radial route along the Parkway E line not extending beyond Ringway 3 is a demonstrable traffic need and in the absence of such evidence it does not appear that Parkway E is an integral or necessary part of the Ringway conception.

Lambeth argued that the GLC had no plans to build it for another 30 years - in which time, who could say whether it would still be worthwhile - but safeguarding the route was sterilising land in the here and now, preventing development of an industrial area in West Norwood and blighting Inner London neighbourhoods. The safeguarding should be lifted, they said, at least to allow tin shed industrial units, which would be life expired before the motorway was built anyway.

Layfield and his panel agreed. Parkway E was doing more harm than good, and there was no clear evidence that it was justified or even useful. Making a nice even pattern of motorways around London was not reason enough to pursue it.

Parkway E did not appear in the finished Greater London Development Plan in 1976, and in fact hadn't been mentioned for several years before then. It hasn't been seen since. Perhaps it was only ever a solution looking for a problem.

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Safeguarding plan showing line of Parkway E extracted from HLG 159/2441.

- 1947 planning map extracted from MT 106/5.

- Photograph of Railton Road is taken from an original by Des Blenkinsopp and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Aerial photo of Crystal Palace is courtesy Britain From Above, EPW021375. © Historic England. Used under the "blogging use" licence terms.

- 1963 LCC plan is extracted from MT 106/195.

- 1970 GLC optimum route spacing diagram is extracted from HLG 159/1024.

- Photograph of West Norwood Car Breakers is taken from an original by Robin Webster and used under this Creative Commons licence.

Sources

- Loughborough Junction interchange and route Brixton-Tulse Hill: GLC/TD/DP/LDS/02/097

- Route Tulse Hill-Addington: HLG 159/2441

- Rees Jeffreys proposal for avenue to Crystal Palace: Plate LXX, Vol. VI. Barbour, David; et al. (1905) Report of the Royal Commission on London Traffic.

- Bressey route from London to Crystal Palace and "New South Eastern Outlet": Routes 21 and 26, Highway Development Survey: General Report (1937), Sir Charles Bressey and Sir Edwin Lutyens, available at MT 39/360.

- Abercrombie's Parkway E and parkway concept: p76, p107-8, Greater London Plan (1944), Patrick Abercrombie, University of London Press.

- Croydon safeguarded land by 1948: MT 106/5

- LCC initial plan including "Hastings Radial": MT 106/195; GLC/TD/DP/LDS/02/097

- GLC optimal route spacing: HLG 159/1024

- Phasing of Parkway E as post-1991 and lowest priority: HLG 159/572; HLG 159/1024

- Post-1991 extension of M23 to reach Parkway E

- LB Lambeth evidence to GLDP Inquiry: HLG 159/1373