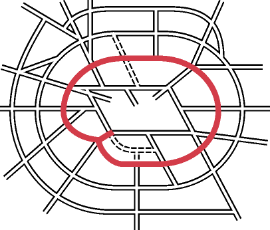

Ringway 2 was the direct replacement for London's inadequate North and South Circular Roads, creating a motorway-standard ring road about six miles from Central London. It was supposed to allow easier movement around the city for people living and working in the suburbs.

By the 1960s London already had a ring road about six miles from the centre, but it was nothing like a motorway. The North Circular Road had been built in the 1920s, picking its way through patches of open land from Ealing in the West to Woodford in the East. The need for it to become a full circuit was recognised in the 1930s by Bressey and then in the 1940s by Abercrombie, but ambitions to create a matching South Circular were punctured by the Second World War. A substitute then came into being as a signposted route along existing streets.

By the time the Greater London Council were drawing up a motorway network, they were faced with a purpose-built (but badly outdated and congested) road in the west and north of the metropolis, and a ramshackle collection of backstreets in the east and south. The easier task, upgrading the existing North Circular corridor to modern standards, fell to the Ministry of Transport, since it was a trunk road and already their responsibility. Those plans were already in hand. The GLC faced the bigger challenge: building a new road through the suburbs from scratch, and providing the starting point for a half-way acceptable road network for South London.

While Ringway 1 was planned as the starting point of most of London's radial motorways, not all would reach that far in, so Ringway 2 would also form the terminus of several major routes, including the A10, M12 and - most importantly - M23.

The appalling state of the road network south of the Thames called for a solution anyway. But the GLC reached for a greater justification, one that went beyond simply replacing an inadequate ring road.

Each of their orbital roads had a specific purpose. Ringway 2's calling - and the rationale for bulldozing swathes of leafy middle class semi-detached houses from Eltham to Wandsworth - was to enable orbital travel within the urban area, providing smooth journeys between suburbs ill-served by a public transport network focussed on journeys to and from the centre. Commuters who lived in Barking and worked in Croydon, deliveries from Hendon to shops in Barnes: these were the trips Ringway 2 would serve.

But the demand for orbital travel in the increasingly decentralised city meant that a huge road was needed to satisfy the traffic projections, and it had to be right in the thick of the suburbs - not in areas designated for slum clearance, and not through the industrial districts or brownfield land that other roads further in or further out could sometimes utilise. That was fine on the North Circular, where a corridor had been established before the surrounding suburbs had developed. But in the south, the planners were forced to blast a new line through well-off suburbia, and the name "Ringway 2" became synonymous with the worst horrors of the urban motorway programme. The GLC's claims that it would improve house prices fell on deaf ears.

In the end, the southern side of Ringway 2 was one of the first elements of the motorway programme to be killed off when the public turned against the GLC's plans, effectively taking the M23 with it, and the Ministry's upgrades for the North Circular stalled in the years that followed. But the need to move around London's suburbs more effectively never went away, and when the GLC was abolished in the 1980s the Department of Transport announced plans for huge upgrades to the North Circular and a new part-tunneled South Circular.

Those plans gave us the fast dual carriageway sections of the North Circular that exist today, but the southern section faced the same opposition that saw off Ringway 2. London is left where it has been for the last century: blessed with a mostly decent ring road to the north and west, and cursed with no way of providing one to the south.

The following pages describe the route of Ringway 2 clockwise from the M4 in West London.

Picture credits

- Archive photograph of M23 interchange architectural model is used under licence from London Metropolitan Archives, City of London (Collage record number 247786).

- "Ringway 2" booklet cover and photograph of Catford are from Greater London Council, "Ringway 2: Norbury to Falconwood" (1969), Collins & Wilson, London. Scan kindly provided by Mike Ashworth.

Sources

- R2 to replace South Circular Road: Greater London Council, "Ringway 2: Norbury to Falconwood" (1969), Collins & WIlson, London. Scan kindly provided by Mike Ashworth.

- R2 to allow easier movement around the suburbs: Greater London Council (1969) "This way to London: A summary of the Greater London Development Plan".

- Claims R2 would improve house prices: "New Giant Shadows the Streets", Evening News, London, 17 July 1969.