The pictures in this section document the construction of the final length of the M65 between Preston and Blackburn. This page outlines its history: why is there a motorway from Preston to Colne, and why is it one of the UK's newer routes?

Most of Lancashire's modern roads can be traced back to a single document written by one man: the Highway Plan for Lancashire, a hefty book full of maps published in 1949, and written by the county's Surveyor and Bridgemaster, Sir James Drake - the man often remembered today as the father of the motorway network.

The M65 is the exception. Drake never envisaged an east-west route linking Preston to Blackburn, Burnley and Colne; he was mainly focussed on links between Manchester and Liverpool, and connecting Lancashire's other major towns to those two cities. It wasn't until the 1960s that a report was commissioned with the intention of improving connections to North East Lancashire, and it recommended the construction of an "east-west fast route", a dual three-lane motorway from Preston towards the Pennines.

It took a decade for the project to get under way, partly because it was the first to be subjected to a new method of public involvement in the design process. The first section of brand-new M65 opened in 1981 near Burnley, and through the decade another four short lengths were completed, creating a strange route from Blackburn to Colne that locals called the "road to nowhere". Its aim was to connect North East Lancashire to the wider world, kick-start its regeneration and bring prosperity to a struggling region, but in its unfinished state it did none of those things.

No through road

The missing section, from Preston to Blackburn, was the most difficult, because the route had been sketched out in the 1960s and - in a decision typical of that decade - it was supposed to pass through the centre of Blackburn. The western end of the unfinished route was at junction 6, where the terminal junction was laid out (as it still is) with space for a flyover that would continue the motorway in to the middle of the town.

That idea, unsurprisingly, wasn't especially popular, so the Department of Transport decided to involve the public again, and in 1975 mounted a consultation exercise on an unprecedented scale that offered a choice of six routes. Two would see the M65 pass through the middle of Blackburn, as planned; the other four were dual carriageway bypasses of the town that would be built as A-roads. The public choice was the green route, which was one of the least economical and which had been rejected in the original 1960s report at an early stage. The green route was announced as the preferred route in 1977, and then dropped from the roads programme in 1980 - so the M65 was already orphaned from the national motorway network before its first section had opened.

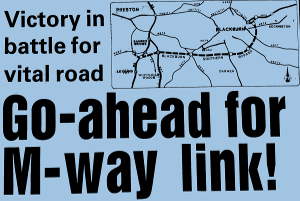

There followed a long fight, mounted by Lancashire County Council and backed by MPs and the various other local authorities linked by the brand new road to nowhere. They succeeded in getting the Blackburn Southern Bypass returned to the roads programme in 1984, but still not as a motorway. In the end, four years later, Transport Secretary Peter Bottomley caved in to the relentless pressure from across the county, agreeing the road would be built as a two-lane motorway, adding about 15% to its construction cost. A motorway, he announced, would give a more effective boost to the economies of Blackburn and Burnley.

A fight at every step

The trouble wasn't over. The public inquiry was the next hurdle, a rancorous event held at a disused Indian restaurant, because Blackburn Town Hall had been the target of a fire bombing attack in the weeks before it began. Multiple complaints were raised against the Department of Transport for failing to exhibit planning documents and notify landowners of their plans, and there were disruptive demonstrations from the Green Party, the Save the Heart of Lancashire Campaign and a one-man protest calling himself the Campaign Against Corrupt Planning. There were also a lot of complaints about the toilets in the disused restaurant.

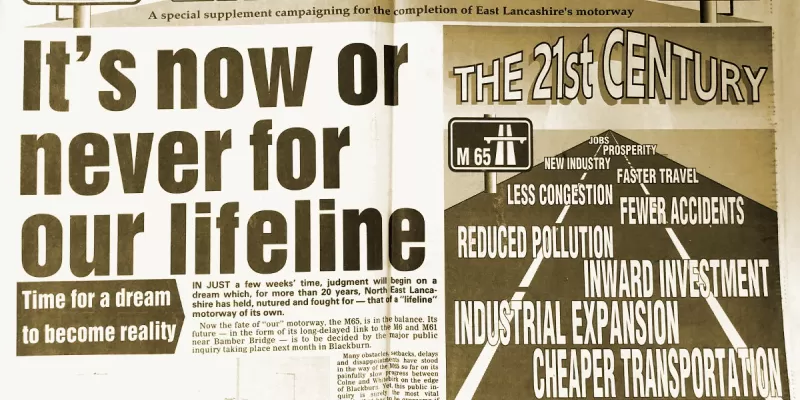

But the plans had strong support not just from local government but also from the locals themselves, many of whom turned out to complain about traffic levels on the existing A677 between Preston and Blackburn. The local papers were strongly in favour too, with the Lancashire Evening Telegraph running an extensive special supplement called "Lifeline 65" to mark the start of the inquiry. The headline - "it's now or never for our lifeline" - was nothing short of high drama, with page after page of argument for the motorway to be built and rebuttals of every possible concern.

In the end, the motorway was approved for work to start in 1992, but the date was pushed back thanks to the recession of the early 1990s, and work finally began on site in late summer 1994.

Environmental concerns wouldn't go away, though. The motorway passed through Stanworth Valley, a thickly wooded site on the banks of the River Roddlesworth, and destroyed an area of ancient woodland at Cuerden Valley Park, where the massive Cuerden embankment would devastate the valley of the River Lostock. Environmental protestors moved in to a treetop camp at Stanworth and battles with the contractors and police followed.

There was also a great deal of unhappiness among the residents of the village of Brindle, who were already displeased that the motorway would pass so close to their homes. Adding insult to injury was the news that the M65 scheme would require far more material for embankments than would be collected in excavating its cuttings, and to find the extra material, Brindle would be the site of a vast "borrow pit" - effectively taking an area of farmland and digging out thousands of tons of earth to use on the motorway project. The site was landscaped and returned to farmland afterwards - in a state of much reduced altitude - but the borrow pit did not help the M65's green credentials.

The road to somewhere

The 13-mile length from Preston to Blackburn was split into two construction contracts. The first, contract 1, was let to Tarmac, who started work in summer 1994 and built the length from Bamber Bridge, just south of Preston, to Stanworth. The 466 pictures available to view here are all of contract 1. The second contract, from Stanworth to Whitebirk on the fringes of Blackburn, started work a little under a year later. The road opened to traffic in December 1997, and when it did - after 16 years - the road to nowhere became a road to somewhere.

In some ways the M65 is still unfinished. The aim, when it was designed in 1989, was for it to be extended further west, forming a western and southern bypass of Preston, terminating on the M55. This never happened, but its odd terminal junction at Bamber Bridge was laid out ready for its onward journey. And the whole of the 13-mile route opened in 1997 was built with the intention that it could later be widened to provide three lanes each way, including extra width over and under all its bridges to allow for the extra carriageway space. That extra room - and the space for the flyover across junction 1A - are still waiting.

Sources

- Various cuttings from the Lancashire Evening Telegraph and Lancashire Evening Post, 1981-1995.

- "M65. A682(M6) to Whitebirk (J1A to J6)", The Motorway Archive.

Picture credits

- "Go-ahead for M-way link!" was published in the Lancashire Evening Telegraph, cutting undated, 1988.

- Photograph of inquiry was originally published in the Lancashire Evening Telegraph, 14 February 1990.

- "Lifeline 65" supplement was published by the Lancashire Evening Telegraph on 16 January 1990.

- Photograph of blue sky above the M65 is adapted from an original by Anthony Parkes and used under this Creative Commons licence.